Why It Matters More Now

Three years ago I produced the video below for Roots Tech. They were holding a contest for their annual family history event. Their purposes for such a video are obvious but for me it meant more.

The video is a variant of a theme I had produced earlier in another video about the importance of photography in family history. It was a personal project, one that made me weep then and one that still evokes great emotion – which is kind of the point of the message of the video, too.

Of course, I didn’t place in the contest. But the video has been used in a few church family history events and occasionally I get comments from folks who stumble upon it.

But the video has another story I feel compelled to share:

Winter of 2019, when the video was made, was the last time Roots Tech was held in Salt Lake City.

That was just a different time altogether. So much has changed for us all since then.

Back then my home was filled with children and grandchildren. I was working at a different place. The world at large was hardly at peace but it was not the drama and chaos it has since become.

My Dad at that time was living quite independently and getting along pretty well. He was traveling, enjoying visits with family at various events and keeping his cancer in check.

As with most things associated with this website and my efforts in family history Dad was supportive.

His journey with family history was different than mine. But in time this video shifted it all for him.

~ Dad’s Family History Journey ~

Our heritage has always been special to my father. It was just how he was raised. My grandparents were, in my view, pioneers of family history.

In my “treasure room” I have among my father’s things a file box that belonged to my grandparents. In it are examples of how family history was done in the 1940s to the 1970s. There are lots of family group sheets – and copies of letters sent to various entities seeking records of ancestors.

I often wonder what Grandpa and Grandma would think of the Internet and all we do with family history today. Grandpa, I know, would take to it like a fish to water.

In the days of my father’s upbringing family history was celebrated with stories, reunions, pictures and gospel discussion about why it is important.

But as the video suggests my interest and love of family history came as a result of my mother, not my father.

It’s not that Dad wasn’t interested.

Dad just figured a lot of his family history was “done”. He didn’t have the at-the-ready memory of all family past stories of my grandparents but he held his own pretty well. And that’s because it was just the culture of his family growing up to talk of those who had gone before.

But Dad didn’t have a Book of Remembrance. He never created or even looked at a family tree. His was, like many people, a secondary level of involvement. Family history for Dad was something of a spectator sport.

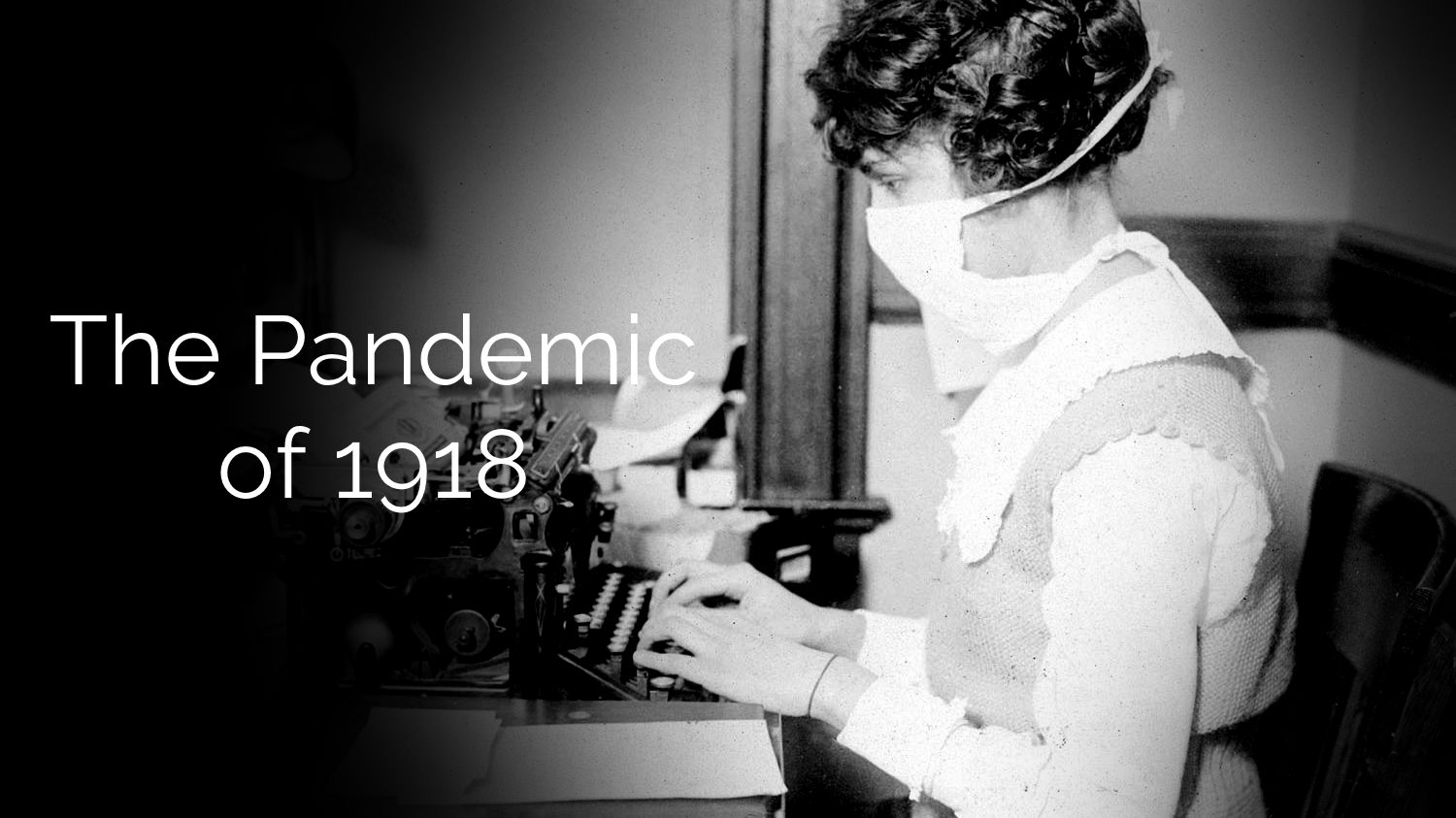

Dad’s family history journey took an unexpected turn when he met and married my mother. My mom was an only child and came from a difficult and disjointed family history situation. Hers was a blank slate and Dad did quite a bit to help my mother discover her family.

Because family history was important in the culture of his family growing up my Dad helped my Mom with her family history – at least for the sake of us kids. But again, while Dad lent his talents to the effort it someone else – my Mother – who put together the groups sheets, the photos and that side of the family tree.

In 1984, after returning home from a mission, I was living and going to school in Salt Lake City. I got a call one day from my father telling me that Grandma was coming to Utah to visit her sister, Aunt Elma, and to visit the brand new Family History Library adjacent to Temple Square. My job was to pick her up at the airport and to take Grandma and Aunt Elma wherever they required. Dad made me call him every day to see that all needs were met.

It was an easy assignment for me and I so enjoyed their company I moved my schedule around as best I could to be with them all day long. So I got to visit the brand new library as well.

In going there Grandma showed me how it was organized and how I could find information. In no time I was threading microfilm into readers and making copies of filmed documents. Wisely, Grandma instructed me to work on my mother’s line because she knew those records would be there and easily found.

She was right. I found stuff almost instantly and began calling my Mom each day as well with news of my discoveries. It ended up being a very exciting week for both Mother and me and it most certainly lit the fire of addiction in my family history pursuits.

~ My Own Family History Journey ~

This opened a dialogue between me and both of my parents about family history.

I made the decision after that week’s experience to drive to Minnesota, where my mother’s father’s family still lived. My goal was to meet my great grandmother, who was still alive.

I discussed this with my cousin, Bunni, and her father, Pete, my great uncle. They were supportive and felt it could happen and that it would be a good thing.

My Mom was very nervous about it. She had heard rumors of difficulties and misunderstandings between her mother and various family members after her Dad died in World War II. Of course, she never knew her father or his family. Her mother remarried after the war and for whatever reasons they were never in her life.

So Mom’s reticence about me going to Minnesota was perfectly understandable. She was still supportive and hopeful.

Dad, on the other hand, was not convinced all this was a great idea. He wanted me to wait. It had more to do with him just being a Dad concerned about a 21-year old son driving cross country by himself to somewhere he had never been before.

Well, I went. It was a joyous experience, one that left me with more questions than answers. But also one that allowed me to meet so many good people – family! – that I have never known. I also came home with copies of precious pictures and a more complete understanding of this largely unknown branch of the family.

No, I did not get to meet Grandma Begich. It was not in her heart to give in to the pleadings of Pete and Bunni and that was because in the tenderness of a mother’s heart it was still too much to deal with after losing her son in the war.

My Mom was a little hurt by that. She took that as a rejection. It would take her many years to come to understand. My Dad was frustrated by it too.

But there were hidden blessings by that whole experience. It fueled continued discussions between us, one that drove our efforts to seek out more information about my mother’s family.

It gave all three of us – Mom, Dad and me – a common goal that proved foundational in the years ahead of family history exploration.

~ The Video: All Sides of the Family ~

When I put the video together of course Dad and I talked about it.

Being who he was as an educator and a producer of television and video productions Dad peppered me with questions about my choices for the video.

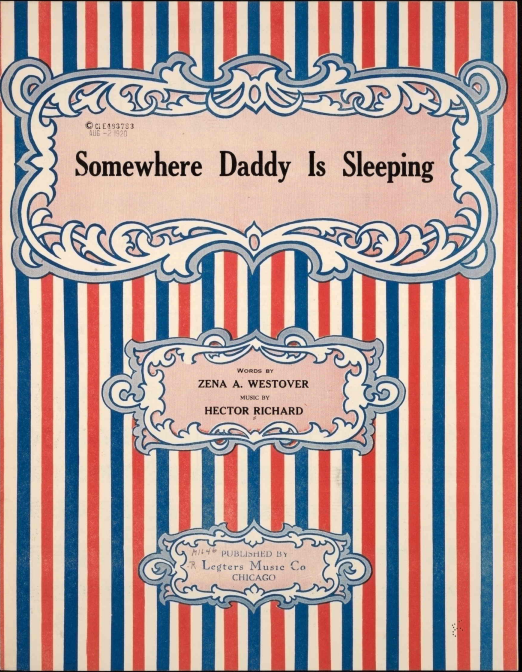

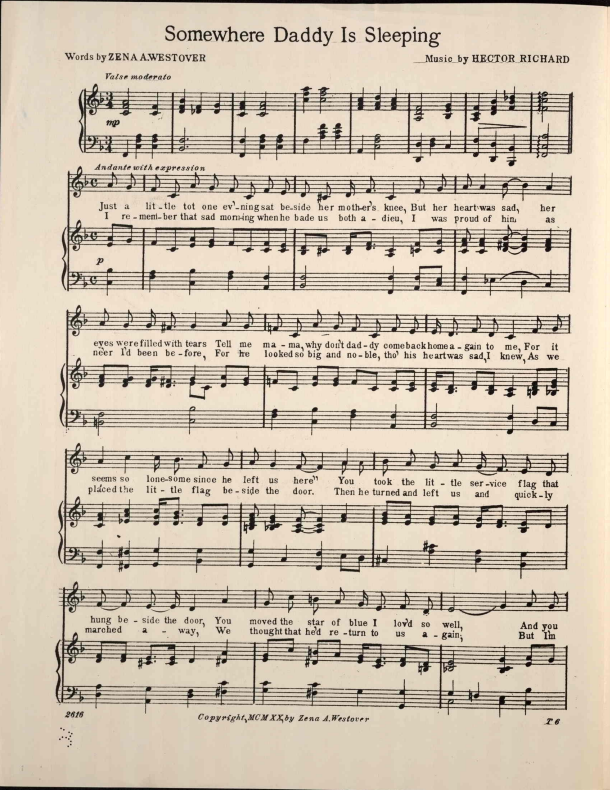

One of his observations was that I began the video on his side – the ancient Westover family history we know – but ended it on my Mother’s side of the family. He thought that this would be confusing to people.

I learned long ago that when teaching a class or giving a talk my Dad would dissect it as if he was the one putting it together. As such, he always began with the objective – what’s the point of what you’re saying? – he would always ask.

Four or five years ago Dad and I both taught Gospel Doctrine for a period of time. Our Sunday phone calls would frequently become a gospel discussion of our lessons and how we would teach them.

I frustrated Dad a great deal because I never approached my church teaching with his methods of having a lesson objective at the top. In fact, I rarely went into these lessons with notes. I had studied and I had prepared. But I had learned as a missionary that gospel teaching was something different.

We didn’t disagree in these conversations. But we challenged each other and commiserated about our teaching experiences. It was a fun time, at least for me.

But when it came to this video, Dad was a little bit bothered, I could tell, and for a while I thought it was because my free-wheeling style was just too uncomfortable for him.

I learned later I was completely wrong about that.

This video turned out to be the catalyst that took Dad off the sidelines of family history.

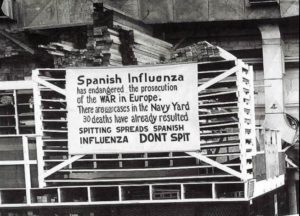

In the late summer of 2020, as the pandemic raged, I continued my weekly phone calls with Dad as we isolated 100 miles apart. I grew concerned in these calls as with each passing week he seemed to sound worse and worse. I wanted to come see him but he refused, insisting he was fine and that we needed to stay within the guidelines of not gathering as family.

By the last week of September, he sounded so bad I just defied him and showed up at his door.

Conditions were not good. He absolutely needed help.

But I had not even been there for 20 minutes when a phone call came in that created no small amount of chaos for us both. His Covid test was positive and I was now exposed. The now familiar-to-everyone family drama ensued. I was forced now to isolate – 100 miles away from my family and my brand new job – and Dad was now forced to contend with the virus as a cancer patient.

That began my 15-month journey of taking up residence with my terminally ill father that would see him eventually pass away in November of 2021. That also began a new level of discussion about all things family history.

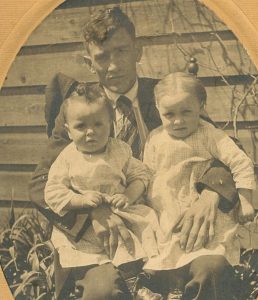

That discussion really began with picking this video apart. One night in October 2020 Dad and I pulled the video up and stopped it at each image. Then from a laptop on his bed, he compared the names and faces to where they landed on the family tree.

Finally, Dad was taking the deep dive we all need to take when it comes to family history: how does all this apply to me? How do I fit in with these people?

That five hour discussion – of both his family and my mother’s family – led to tears, something that was rare to see from my father at that point.

He already had an appreciation of his family and an abiding love for his heritage. But now he had details. Now he had personal connection. And it set him on fire.

During Dad’s last 15 months he fought all kinds of crazy physical sickness. But when he could set that aside he became very focused on family history. He began to piece in his mind ways to better share the history and connection with other family members.

He started working on writing my mother’s history and then working on his own. As I would work on my various projects we would discuss them and Dad began to embed himself in everything.

My projects became his projects, and his mine.

Last spring, in 2021, after many discussions with LaRee and Will, Dad found the energy to go on a little tour of cemeteries in southern and central Utah. What made it neat was to see him connect with ancestor past by recalling his own early years in Southern Utah and the places he lived there. He never knew – and likely because my grandparents never realized or knew – that they lived in the very shadows where beloved pioneer family members did their pioneering.

It was thrilling to watch Dad connect his early childhood to those ancestors who were right there less than 100 years before he was born. Though his body was falling apart and challenged with getting through the long days of that trip it fueled inspiration in how Dad felt the family story could better be told.

Even while we traveled Dad began to make plans for written histories, videos, and website features to, as he explained it to me, “get people to look at the tree and connect”.

In fact, on the day he unexpectedly died, we had refreshed the list and prioritized it. He wanted to get back out there. He wanted more pictures, more videos and more understanding that could be found.

His list is now my list. I know exactly what he envisioned and frankly I don’t know if I have enough years left to accomplish it. That’s how ambitious Dad became about family history.

We last watched this video together about two weeks before he passed. At the time, I had gone to bring home my wife from caring for her folks so she could be home for the birth of a new grandchild. Dad was very invested in my daughter’s pregnancy and he was anxious for the little boy that would come to us.

On the night we watched this video again he told me that I had to make sure this new baby would see that video when he was old enough. I found it kind of a curious charge – because my goal has always been to get this video in front of the eyes of my kids and grands.

Dad passed in the early morning hours of November 16th. Baby Bennett was born later that same day.

Yes, the video, which already meant a lot, means more now.

That’s my lesson on several levels. It was also Dad’s lesson in his family history journey.

I have over the past several months since he left contemplated what it must have been like when he unexpectedly crossed over.

He knew faces. He knew names and dates. He understood connections.

This is what family history does for us. I think we all come around to it a little differently.

I don’t condemn my Dad – or anyone else – for being so absorbed by life of the present to the point where delving into life of the past is impossible. We have to grow up, get educated, build careers, and manage the stuff of the here and now. I get it. I was there for 50 years and guilty of not really getting into it.

The point is not when. The point is not whether you have the skills or the technology to do it.

The point is that we can. Despite it all, we really can. And we really need to. And it’s really worth it.