A Tale of the Old West and Bad Family History

Tonight I went fishin’ for a while. I don’t get nearly enough opportunity to do that –“fishin’” as it relates to family history.

Here’s how it works: I go to FamilySearch or Ancestry and enter very broad search terms – say, a surname like “Smith”.

Then I sort out all the results to drill down to just what I want to see. Sometimes it is birth certificates, sometimes it is census records, sometimes it is just something else.

Tonight it was photos.

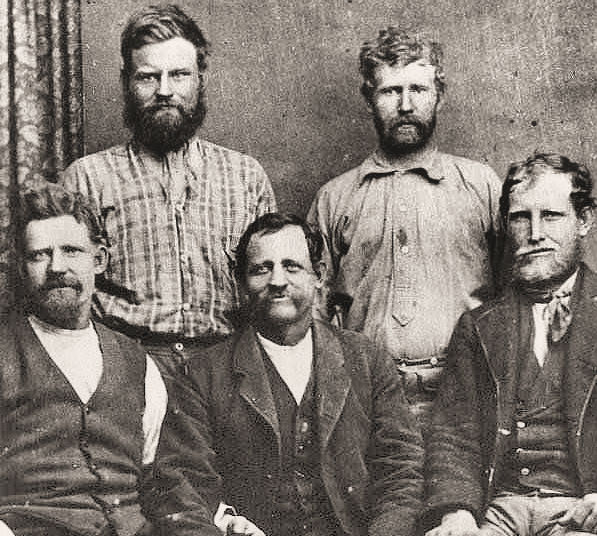

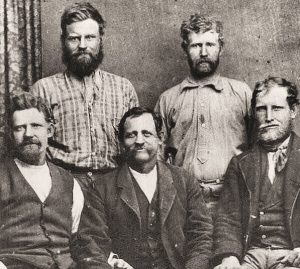

I went to Ancestry and trolled for all photos I could find associated with “Westover”. I got that beauty of an image above from this little fishing expedition.

Those boys are brothers by the name of Canfield.

Those boys are brothers by the name of Canfield.

I had seen that name somewhere before so I had to click on it and figure out the connection.

I got the connection alright – but the side story was a much better find – a true tale of the old West.

What made it even better was the alleged mystery of a 120-year old event spilled over on the pages Ancestry as descendants of the men involved continued to debate the tale of cattle rustling, old west gangs, suicide and murder.

Interested? Read on.

First, the family connection: the man in the bottom left of that picture is Moroni Canfield.

This picture of Moroni and his brothers was taken in about 1890 – about three years before Moroni died – or was murdered or committed suicide, depending on whose history you believe.

Moroni married Sarah Evaline Westover, eldest daughter of our Edwin R. Westover and his wife, Sarah Jane Burwell.

Moroni and Sarah met around 1870, when Edwin was living in Hamblin. Both were about 20 when they married.

Edwin has no real part to play in this story. After Moroni and Sarah were married they left Hamblin for several years and returned in 1877, where Edwin traded his property there to Moroni for a team, harness and wagon for Edwin to use on his mission to Arizona.

Moroni and Sarah would have a family of 8 children and his life until the 1890s mirrors that of so many in Southern Utah from that time. They struggled financially and fought the elements in their attempts to build Zion.

With a name like Moroni you have to know there is a strong Mormon connection, too.

Moroni’s father joined the Church, went to Nauvoo and later to Winter Quarters where they came west when Moroni was just a boy. He was thoroughly invested in the Church.

A story is told of how Moroni once came upon two US Marshals who were in Utah hunting down polygamists.

Moroni asked these two men why they were there and the marshals shared they were on their way to Enterprise to arrest Thomas Sirls Terry, a leading figure in that community and a known polygamist.

Moroni was able to give the marshals the slip and get to the Terry farm to tip off the family, who got “Ol Man Terry”, as the marshals called him, out of town just in time.

That story is told in contrast to the real criminal activity that the ranchers of southern Utah had to deal with in horse and cattle thieves.

The Canfields lived not far from a place called Desert Spring, which happened to be a crossroads of sorts between Beaver, Utah, Pioche, Nevada and Utah settlements to the north and mining camps to the south. Desert Spring was also the base of operations for a man named Ben Tasker, a genuine old west outlaw.

Tasker was known for his gang of outlaws who would first provide aid to travelers passing through Desert Spring and follow them for short distances only to rob them in the middle of nowhere.

Their primary source of income came in the way of cattle and horses – and Tasker’s gang stole them by the hundreds, changing brands or butchering them to be sold in the mining camps.

There are legendary tales – some untrue, I’m sure – of just what a tough customer Tasker was.

One story talks of him shooting a man and then using his body as a table while Tasker played cards.

The Canfield brothers knew too well how lawless the times were and they had a personal connection to Tasker.

Their sister, Lucy Philena, was married to a man named Thomas Emmet.

Lucy Philena’s history talks a bit about the woes in her marriage. Though she and Thomas were married in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City when they returned to Southern Utah and started their family it seemed that Thomas wasn’t around much. The history says he traveled a great deal “on business”.

His business was “his dealings in cattle and horses”.The Moroni Canfield history on Ancestry is a bit more descriptive of Thomas’ activities.

According to their version of things Thomas rode with Ben Tasker’s Gang and neglected his wife and small children for long periods of time.

The Canfield family did all they could to help Lucy Philena but they grew weary of Thomas’ antics and were constantly rescuing him from the trouble he would get into.

On the night of June 28, 1893, Moroni and a few others were herding about 1500 head of cattle when something happened.

In the morning, Moroni was found dead – shot in the head.

From Moroni’s history on Ancestry we read of why some descendants of Canfield felt Thomas Emmet and Tasker’s gang had something to do with Moroni’s untimely death:

“Emett was a pretty rough character. He and a friend Bob Tait ran and dealt with the Ben Tasker Gang. Ben Tasker was a horse and cattle thief operating all over the territory. He had his headquarters at Desert Springs, at the junction of roads from Beaver, Iron Springs, Mountain Meadows and the Nevada mining camps.

Ben Tasker had been arrested numerous times, but always found some way to get away. He and his men would take what they wanted and kill anyone who stood in their way.

The Canfield brothers because of their sister had been trying to keep Emett out of trouble and talk some sense into the pair. Nothing worked. They grew tried of seeing Philena and her little ones hungry and without proper care. She had lost a number of babies by miscarriages. They were sick to death of pulling him out of a hole and trying to feed and clothe this little family.

So, they decided to catch Emett in the act. Well they caught him and Bob Tait both in the act. Stealing Cattle.

They had come prepared so they pulled their guns on him and Tait and told Emett they were sick and tired of getting him out of his messes. That the law was on to them and was out to get them.

Now, Grandfather said, I told him “I do not want to see your face any more in Utah or close about. You head for Texas as fast as you can. It will be less costly for us to take care of your family than to bother with the likes of you. If we ever see you around in Utah again I personally will shoot you.”

[Insert spookly old west whistling music here]

Thomas Emett evidently didn’t need to hear any more.

He lit out of Utah heading south and that was the last the Canfield’s heard from him – until Moroni ended up with a bullet in his skull.

To quote again from the history on Ancestry, “Moroni and the Canfield herd would have been in the right place and the right time to be easy pickings for Thomas Emett or one of his associates. Revenge is as good a motive for murder as money, and Emett had both.”

The surviving family of Thomas Emmet doesn’t care for that version Canfield family history. They have a very different point of view.

Another family historian on Ancestry – a descendant of Thomas Emett – was able to prove that not only was Thomas hundreds of miles away in Arizona at the time of Moroni’s death but he was also, fortunately, dead, too.

Thomas had died 10 years before – in Phoenix, evidently of smallpox.

Yes, thanks to the modern sleuthing of family historians, they cleared the name of Thomas Emmet from the charge of murder.

That doesn’t mean the controversy had diminished. His memorial on FindAGrave.com, after several contrary comments, now notes:

“There are many unsubstantiated rumors that still persist even after 125 years. I have letters, life stories, and 1st hand accounts of what happened to Thomas. My great grandfather, Don Thomas Emett, his son, told others to ignore what people say, we know what is true. We are told by the authorities to not gossip. It is sad 125 years later people can’t wait to tell me how bad my great-great grandfather was.”

Thomas’ family had long compiled proof of his innocence, most notably the receipt of his spurs and his saddle, which were shipped to them after he died.

Even still, it wasn’t hard to make the connection to Tasker or to Emmet.

Tasker at the time of Moroni’s death was in jail in Beaver, Utah. His reputation as a frequent escaper from jails was legendary because his roaming gang would often overwhelm lone guards or sheriff personnel.

Tasker’s men were in the area – and revenge was not their only motivation in what Moroni was up to.

Moroni, you see, was then under contract to move and sell and very large herd of cattle – right through the heart of west central Utah where Tasker did his most notorious work.

Perhaps that was a reason why Moroni took the job – one that would change fortunes for him and two of his friends.

That transaction was nearly complete, all Moroni needed to do was to finish the move, a task that took him near Beaver and a task that proved to be much more difficult than he anticipated.

Moroni had a pocketful of money but what he had collected to move the cattle was dwindling fast and he would find himself in a negative cash position if he didn’t deliver soon and deliver as many cattle as possible.

A news report of Moroni’s death explained his fate was sealed by the weather, a lack of manpower, sleep and the realization that Moroni had lost big on his deal.

Moroni Canfield, they reported, killed himself after a midnight thunderstorm scattered his herd and he felt all was lost.

For decades the descendants of the Canfields and the Emmets held to their respective stories about the demise of Moroni Canfield.

But the ultimate vindication of Thomas Emmet came from an unusual source – Moroni’s mother, Elizabeth Canfield.

In 2013, a family member posted to FamilySearch a letter that Elizabeth Canfield wrote in July 1893. She told a vivid tale of horror at learning the real story of Moroni’s demise.

She described how Moroni had “been in the saddle” for three days without sleep, trying to keep the cattle together all while wrestling with a fast coming financial disaster. The longer it took him and the more cattle he lost the deeper the hole he was in.

The combination of financial stress and physical exhaustion led Moroni to one very sad conclusion.

Elizabeth writes:

“The night before he did this his reason left him. Pratt [his brother] could do nothing with him. He tried to get him to go to bed, put his arm around him and tried to get him to lie down and that was the night he was to get to water. He would not do it and about 10 o’clock the cattle got the scent of water- 1,511 head of them. As soon as they smelt the water, they went wild. The boys rushed after them but could only find 300 head…”

“F. Rice was the only man with a pistol. He took it off and laid it down by his bed instead of putting it under his head. Of course Roni would not sleep and got up. Told a boy to go round the wagon and get his horse. As soon as his (the boys) back was turned, he picked up the thing, put the muzzle in his mouth and fired…”

“…After he was buried, I was looking over his clothes and found a little scrap of paper in his overalls pocket. He told the boys that all was lost. The cattle gone. But if he had only waited till day light he could have seen the stock or the most of them at a distance.

On the paper he said ”I Moroni Canfield have staked all and lost. I have ruined myself and friends. Their names are E.V. Hardy and L. C. Maneger (Marriager?). I have lost all am not fit for a felons cell. Good bye. May Father in Heaven have Mercy”.

Of course, life went on for everyone else.

Moroni’s mother lived until 1908 and is buried in Hamblin. She is remembered for her faithfulness.

Lucy, Thomas’ widow, remarried a man named John Day in Hamblin and they had three children, including a set of twins.

Moroni’s widow Sarah remarried nearly a decade later and lived until 1927.There are many lessons to learn from these tragic events.

For the family of Thomas Emmet, there has to be some joy in his vindication. He may have been a lot of things but he clearly didn’t murder Moroni Canfield.

Not all of our relatives have great things to be said of them. Even still, why would we settle for anything less than the truth?

For those of Moroni Canfield’s family – especially those who laid the blame for his death on Thomas Emmet – what do you have to say for yourselves?

Surely it is hard to be unsympathetic to poor Moroni. He had troubles, clearly.

But as I sat thinking of all this I couldn’t help but wonder about the story of Ben Tasker.

Certainly he has descendants and his history is somewhere, no?

Well…no. At least not that I have found yet.

A Google search seems to return a lot of links back to FamilySearch about this guy. They turn out to be histories of other people – many of them victims of Tasker and his gang.

They were the cattle rustlers of the Old West in Utah, no doubt about it.

I found Ben Tasker living in Beaver in the 1880 census. He’s listed as divorced and living alone. He was 61 years old.

But there’s not much else written about him that I’ve found yet.

For whatever reason I want to know how and when he died. Did he go out in a blaze of bullets? Did he jump off a cliff in Bolivia? Or did he die of old age?

That’s a history hunt for another day.