Where the Name Edwin Ruthven Came From

Tradition within the Westover family for centuries has been the re-use of common first names. Perhaps the most common is “John”. There is also plenty use of the names Jonas or Jonah, William, and, of course, Gabriel. In researching an upcoming video on the life of Edwin Ruthven Westover we have been a bit hung up on his name. Where did it come from and why did Alexander and Electa choose that name for their first born son?

Tradition within the Westover family for centuries has been the re-use of common first names. Perhaps the most common is “John”. There is also plenty use of the names Jonas or Jonah, William, and, of course, Gabriel. In researching an upcoming video on the life of Edwin Ruthven Westover we have been a bit hung up on his name. Where did it come from and why did Alexander and Electa choose that name for their first born son?

There has to be a reason for this, right?

In researching we have found that while we can find plenty of Edwin Westovers in both America and in England in the 18th and 19th centuries we cannot find a connection to our branch of the Westover family. There isn’t an uncle or a distant cousin that we can find who would influence the naming of a baby born in 1824. In fact, in looking at the names Alexander and Electa chose for all their children we cannot find a Westover family connection: Edwin Ruthven, Albert, Charles Beal and Oscar Fitzland have no connection within Westover history whatsoever.

Well, there’s no crime in that and we suppose the reasons are clear enough.

One of the lingering questions in our minds is how disconnected Alexander Westover himself may have felt from the Westover family. (We wonder as well about his faith). Unlike his father he was separated while quite young with most Westovers he may have known:

Alexander was one of the younger children of Amos and Ruth and he was born, it appears, during the transitory years of the Amos Westover family migration to Ohio.

Most researchers feel he was born in Canada, though no official birth records exist that confirm 1798 as the actual year of his birth or the place of birth. Records just say he was born “about 1798” and Canada is where most assume the family was based upon the census records found from the early 1790s for Amos and Ruth.

Alexander was clearly with Amos and Ruth in Ohio when they got there around 1815. In 1821 both Amos and Ruth died within weeks of each other, leaving Alexander seemingly alone in the wilderness without much connection to the old family home in Sheffield, Massachusetts or the growing homestead of his uncles in Eastern Canada. (And, obviously he didn’t have text, email or Skype).

Alexander married the sister of his sister Olive’s husband, Electa Beal — and I’m guessing if he had much of a sense of family at all it came from this association and that of the Beal family.

So family is likely not the influence in naming the first child of Alexander and Electa. So where then did the name come from?

In trying to answer that question we have found that the name “Edwin Ruthven” was quite popular in the 19th century.

A quick search of Google or Family Search reveals thousands of uses of the name, mostly from this time period. What caused that?

The answer? Pop culture.

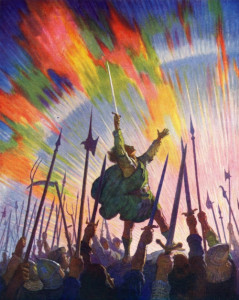

In 1809 a historical novel by the title of The Scottish Chiefs by Jane Porter was published and it became wildly successful. I’ve never read it but the book very much was an influence to youthful readers in the early 19th century in the ways that movies are an influence today. The book is based in 14th century Scotland and details in a romantic and suspenseful fashion the heroic adventures of Sir William Wallace, Robert the Bruce, and — Edwin Ruthven.

How popular was it? Think Harry Potter. That’s how popular it was.

Of course, now I HAVE to read the book. The question in my mind is who was caught by its charms — was it Alexander or Electa? (Or both?)

I’m betting on Electa, at this point, given the romantic nature of the book and the fact that it appears to have been so popular with teenage girls. Electa was born in 1802 — so she would have been a teen right at the height of popularity for the book in the US (it was a sensation in Europe before coming to America).

Can we be sure this is the true origin of Edwin’s name?

No, of course not. And in the grand scheme of things in relation to family history it may in fact not be all that important.

In a more clinical search for the meaning and origin of the names “Edwin” and “Ruthven” we find them to come directly from Scotland.

Edwin was the name of a 7th century King, the first Christian conqueror in Scotland who was famous and beloved — and for whom the city of Edinburgh gets its name.

Ruthven has a dual meaning in Scotland as both the name of a clan but also the name of a place meaning “red river”. There is, as with many words of Gaelic origin, vast confusion over how the name “Ruthven” is pronounced. It is in Scotland pronounced “Riven”. (I’ve never heard anyone here say it that way, though).

This little side note in family history has been helpful to me in a few ways.

First of all, the spelling of “Ruthven” has always been a question in my mind. I’ve seen many instances on official family group sheets of various age that some have spelled it “Ruthvin”. There is enough of that that I have never known which is correct. I’m fairly certain now it is supposed to be “Ruthven”.

But even more important to me is the little glimpse it gives us into the personality of Electa (it HAS to be her) — a bookworm! A romantic! (Would she love The Book of Mormon? No doubt. But what about The Princess Bride? NOT inconceivable).

That makes her one of us, right?

All of this, you know, won’t make the video.

I can’t confirm my theory and, frankly, the story of Edwin is already running long at better than 1500 words.

But, once again, this is just one of the fun little diversions of doing family history — a 30-minute exploration brought on by questions that opens the door just a little more to an endearing part of our family past.