The War Experience of Grandpa Carl

I always try to spend a little time with my grandfather, Carl Begich, each Memorial Day. He is, to my knowledge, the only of our family to have given his life in the service of our country.

Memorial Day is to honor those who paid the ultimate price. Remembering Grandpa Carl by searching anew anything I can find about him or sharing something I have not shared before on Memorial Day is my way of taking part.

It would, in a perfect world, be best to visit his grave and to honor him in person. But he is buried in France and I will likely never be able to visit his grave.

He died on May 18th, 1945. I remember him on that day, too, though it fills me with sadness to think of what that day came to mean to both my grandmother and my great-grandmother – and the rest of his family.Most have an image in their mind of what it is like to lose a family member at war. The visions are of gun fire, explosions or perhaps even tanks and air planes dropping bombs.

But Grandpa Carl was a radio operator and a “code breaker”. From the very beginning he belonged to a unit tied to “Army intelligence”.

This made his war experience quite different and his death shrouded in mystery.

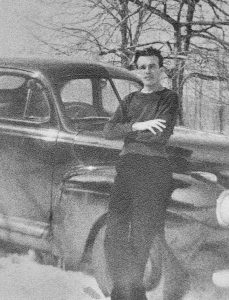

Grandpa Carl was born the third of seven children to Mike and Katherine Begich on January 11, 1920. His was a happy upbringing in a home filled with faith and tradition.

Carl had many pursuits – he was musical, he enjoyed writing and he with his brother developed a passion for the emerging technology of amateur radio.

When he left Minnesota after high school to pursue a career as a journalist in New York City he maintained his radio license and continued to pursue the hobby.

He met and fell in love with my grandmother, Winifred C. Welty, while in New York.

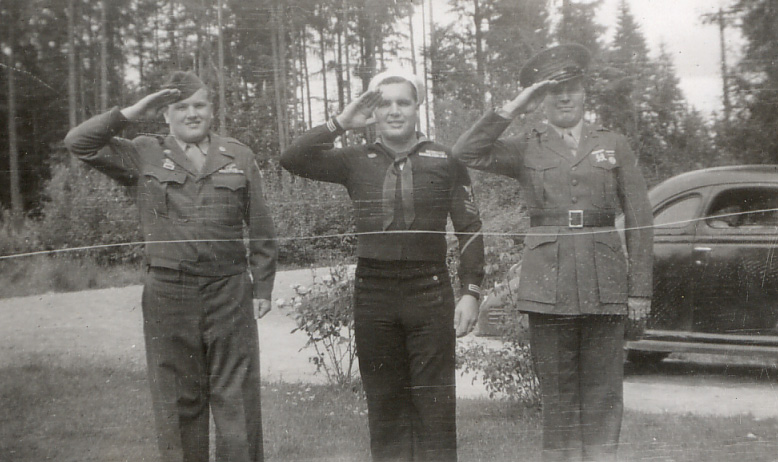

They married in May of 1942. In January, 1943 – on Carl’s birthday – my mother, Susanne C. Begich, was born.

As fate would have it they would have precious little time together as a family. In mid-February 1943, Carl enlisted and was whisked away for basic training.

The Army had needs for a man with Carl’s skills.

For a while they told him he would be engaged in a project helping to break codes against the Japanese. He was told that he would be stationed on the West Coast and was so certain of it that he sent my grandmother and my mother to California to find a place to live.

He never got to them.

Instead by September 1943 Carl was stationed in England, and there he waited with thousands of other GIs for the invasion of France. There he trained with British officers receiving hands-on training intercepting real-time German radio messages at various places throughout England.

World War II, being far more fluid than World War I, marked the advent of the mobile radio intercept unit whose task was to pick up, decrypt if possible, and pinpoint enemy units sending their messages through the airways.In England, late in March 1944 while the English and American armies were feverishly preparing for the invasion of Normandy only two months away, the U.S. Ninth Air Force, whose assignment it was to conduct the tactical air war over the Continent, ordered a Major Harry Turkel to form and train a new unit in time for the invasion.

The new unit’s task was to monitor and intercept German Air Force radio traffic while operating out of mobile caravans designed to keep pace with advancing armies. This new unit was to be aptly named the 3rd Radio Squadron Mobile (“G,” for German). Carl Begich was assigned to this unit.

Over the course of his war experience Carl wrote a prolific number of letters. In sending them home he instructed that they be saved as notes he would later use to write about his war experience.

Dutifully my grandmother saved them and they have become a treasure to us today.

These letters are all we have to know Carl Begich.

From England in September, 1943, Carl said: “I mentioned I was happy here. I meant I got accustomed to surroundings in a hurry and was glad only that I can now consider myself part of this man’s army and this theatre of operations. It had been my desire, inwardly, you know, to be part of this, actively.”

This is an amazing insight to me.

Carl was 23 years old, married, a father, and he knew well the feelings of his mother, who desperately did not want him in uniform and in Europe, in particular, during the war.

Yet Carl had the same feelings of most of who we call the “greatest generation”. He was both duty bound and anxious to serve.

In December 1943 he was missing home.

He wrote: “Reading what you wrote about the little things Cathy got coming for her Xmas and whatnot makes me homesicker than ever. Darlin’, you have no idea just how much I wish I could be there with you and the little darling. Gee…. I am glad you liked that poetry I sent you. Of course, dear, you understand what’s happening to a feller especially when he starts writing poetry. Can you beat it? Undoubtedly, I shall get those nostalgic but really lovely spurts again, I know. And when I do, I shall pass the outcomes along to you to insert in your scrap book. That scrap book idea, incidentally, is a grand one. I am keeping one here, too. Oh yes, my diary is getting pretty plumped these days, dearest.”

He wrote: “Reading what you wrote about the little things Cathy got coming for her Xmas and whatnot makes me homesicker than ever. Darlin’, you have no idea just how much I wish I could be there with you and the little darling. Gee…. I am glad you liked that poetry I sent you. Of course, dear, you understand what’s happening to a feller especially when he starts writing poetry. Can you beat it? Undoubtedly, I shall get those nostalgic but really lovely spurts again, I know. And when I do, I shall pass the outcomes along to you to insert in your scrap book. That scrap book idea, incidentally, is a grand one. I am keeping one here, too. Oh yes, my diary is getting pretty plumped these days, dearest.”

We do not know what became of the personal items of Carl Begich after he died. What we would not give now to have his diary.

In June 1944, Carl sent just two letters home. It is interesting in retrospect to read them, knowing what we do now of D-day.

“Three months ago the fellows in my outfit here began an invasion kitty, destined to give the correct predictor of the invasion date, something like 8 pounds (about $32, roughly). I was very surprised to know that I had won that jackpot….the general concensus of hopes herearound is that perhaps we may be home to celebrate Christmas this year…”

The “code breakers” of Detachment A, 3rd Radio Squadron started their voice-intercept operations a few miles south of Point de Hoc on June 11th, 1944.

After the breakout from Normandy Detachment A served both the 8th Air Force HQ and the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force.

Christmas of 1944 came and with it came the last real Nazi push of the war known as the Ardennes Counteroffensive.

Carl was there, as was the rest of the Ninth Army, and the 3rd Radio Squadron played a big part in turning the fortunes of the war there.

His comments home were vague and revealing at the same time, in a letter from December 29th:

“I’m glad for one thing and that is that you don’t continually barrage me with a lot of queries concerning my duties here. You can find out all about such things from your daily newspaper for from the latest radio broadcasts. Now if you can put two and two together, you will know a story. And if you can make three out of two you will have a superb picture of reality.”

Clearly Carl was in the thick of it and seeing unbelievable things.

At 0415 on December 16th, 1944, the radios of Detachment A came alive with a short but hastily sent message from behind German lines.

It was unusual to get such traffic in the dead of night. The intercepted message was taken to the tower where the late night shift of code breakers started to work on decoding it.

It is impossible to know now if Carl was on duty at this time.

While engaged in decoding a second message came in, exactly like the first.

This was really out of the ordinary.

The code breakers identified the German encryption that was a family of codes they had named after musical composers, an “elgar” used by the Germans to contact their antiaircraft units. It was quickly broken, and read “… 90 JU 52s and 15 JU 88s going from Paderborn area to area 6˚-6˚ 30´, E to 50˚ 31´-50˚ 45´ and returning by same route.

The code breakers plotted the co-ordinates on maps as between Hofen and Monschau on the Belgo-German border. In the dim light of the tower room, eyebrows went up even higher.

JU 52s were transports. JU 88s were versatile aircraft used as bombers, night fighters and occasionally as transports; it was thought they would be used as transports. Never had the Germans used 105 transport planes at night.

Then, an hour or so later a message was received canceling the German operation.

Nevertheless the message had already been sent up the line to Ninth Army HQ and the next day, when the Germans launched the operation for real, the result was a devastating set-back for the Germans that marked the beginning what was to be known as the Battle of the Bulge.

The “bulge” which formed as a result of the German offensive separated Lieutenant General Bradley’s 12th Army Group Headquarters on the southern flank from the major part of the

First U.S. Army and the Ninth U.S. Army, which were located on the northern flank.

Communications between group and army headquarters were cut. To remedy this situation, Eisenhower’s staff recommended that the American Ninth and First armies be shifted to the command of Montgomery’s 21st Army Group which was in the north.

On 20 December 1944, Eisenhower ordered the shift of forces. This decision would prove to impact the life and mission of Technical Sargent Carl Begich.

Under Montgomery, the Ninth Army and the 84th Infantry Division crossed into Belgium and into Germany over the Roer River in what was called Operation Grenade.

Carl’s letters reflect the rapid movement East as he was without a typewriter for a period of time. The letters also stopped coming and going abruptly.

“Things look good over here but not quite good enough,” Carl wrote at last in February 1945. “Those stubborn, bullheaded Nazis have got to be horsewhipped into making them know they are finished.”

While things were advancing quickly towards the war’s end so too were pending changes being felt.

Carl wrote cryptically on February 24th, 1945: “I have a funny premonition that some very funny events will occur shortly which may concern me and you and Cathy…but when and if you do hear of these, do not be alarmed because there will be a reason, at a later date, covering each occurrence….”

In March, he spoke of a longer delay in coming home: “I am very conscious of the fact that our anniversary is due up on May 14th. I am too darned well conscious too of the fact that I will not be home then, and, more so, may not be home for perhaps for the next three years. I believe I may as well face the situation eye to eye…”

What could he possibly be talking about?

By April of 1945 the Ninth Army was well into Germany and the feeling overall was that war would be over “soon”.

But the ending of the war brought continued uncertainty for Carl: “Now that things are coming to a close and now that situations are settling down, what’s to happen? Of course it is needless for me to say just what is on all our minds over here. I almost quite sure that by the time you receive this, this war over here will have been over and won. In such case and as a result of this, will no doubt cause a widespread anxiety over many of you. I hope, though, that you are fortified well enough – so that your hopes will not be shattered; what I mean, dear, is that I have absolutely no idea just what will happen to me after this blows over over here. And neither do the other fellows. We are in the dark and we will probably remain as such for a while yet.”

Fate for Carl was just over the Rhine.

The Rhine is more than a river. It was a sacred waterway to the Germans, the source of most of their legends and myths.

The Rhine is more than a river. It was a sacred waterway to the Germans, the source of most of their legends and myths.

Now it was the last barrier between the advancing Allied armies and the conquest of Germany. If the Germans could hold their beloved river, they might be able to stand off the Allies.

Carl was at the Rhine with the 1.2 million combined forces under the command of Montgomery. The force consisted of the 1st Canadian Army, the 2nd British Army and the 9th US Army.

The Rhine was 400 yards wide at the Wesel crossing point, and to defeat the river and the heavy German fortifications, the 2nd Army alone collected 60,000 tons of ammunition, 30,000 tons of engineer stores, and 28,000 tons of above normal daily requirements.

The 9th Army stockpiled 138,000 tons for the crossings. More than 37,000 British and 22,000 American engineers would participate in the assault, along with 5,500 artillery pieces, antitank and antiaircraft guns, and rocket projectors. They would engage in what would be called Operation Plunder.

The Germans were truly taking their last stand. They were short of nearly everything in supplies and their forces consisted of both the very young and the very old.

By the 28th of March the bridgehead over the Rhine was 35 miles wide and extended 20 miles further into Germany.

Churchill himself was there at the 9th Army’s crossing point.

He reported to Eisenhower personally: “My dear general, the German is whipped. We have got him. He is all through”.

While the war was ending for the Germans it was not ending for Carl.

Carl’s last letter home, dated May 2nd, 1945 from Germany, was even more suggestive of what could happen to him: “…I’ve been reading in the Stars and Stripes about all of these “War Over” declarations making the rounds back there. This all brings to mind a deduction I have made in the past four or five days…and which I believe in…I do believe that a quick trip is in store for myself. As for a majority of the others here – to the far east – possibly India, China or Burma! …One never knows! And, if someone does know, he “ain’t tellin’…for security reasons, both personal and strategic and tactical.”

On 18 May, 1945, under conditions never fully explained and still classified, T/Sgt Carl Begich died – DNB, it says (Died Non-Battle) – in the Rhine River.

Last year, both of his sisters who are well into their 90s, told me the family has never believed it. Carl had a mortal fear of water.

A wedding ring he wore was taken from his finger and sent home to my grandmother. My Dad has worn this band as his own for decades.

Little else is known or was given of Carl’s to the family. Are that are left are questions:

Did Carl really die in Germany?

Did he learn to speak fluent German?

Can more be learned of his work?

How many men were in Detachment A of the 3rd Radio Squadron Mobile?

Did any of them survive? Did they leave a record?

These questions of the war experience of Carl Begich now still matter. As his 100th birthday is noted there can be no denying the long reach not only of his passing but also – and mainly – of his living.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!