The Deseret News this week featured an article about the Manti Temple, telling this famous story of Brigham Young and Warren S. Snow from 1877:

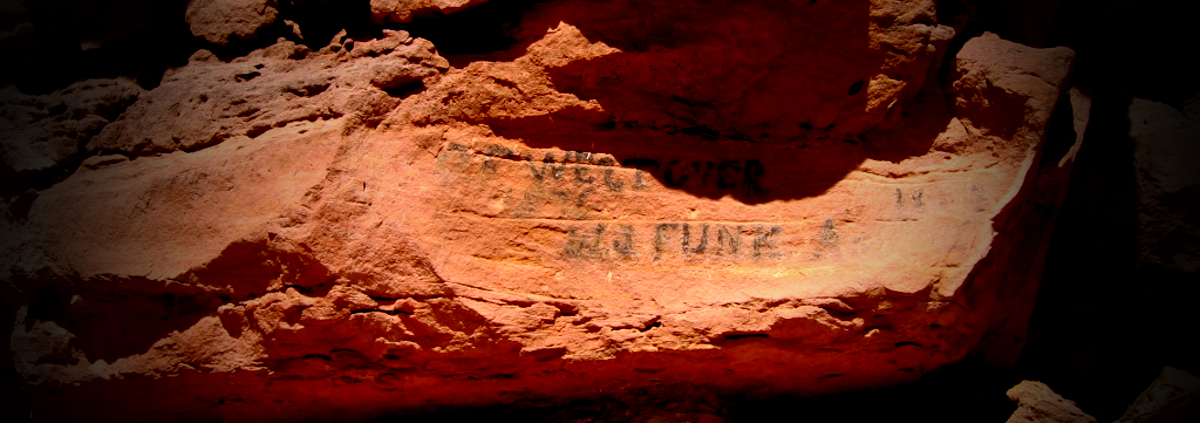

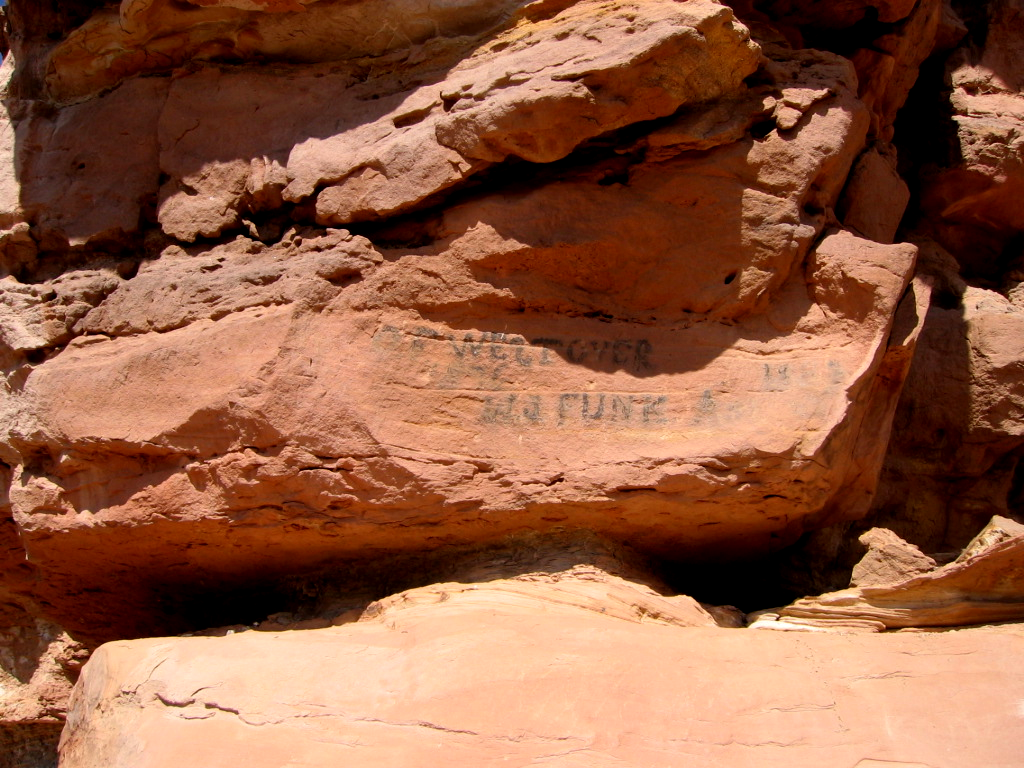

Standing on the southeast corner of the Manti Utah Temple site, Brigham Young told Warren S. Snow, “Here is the spot where the Prophet Moroni stood and dedicated this piece of land for a temple site, and that is the reason why the location is made here, and we can’t move it from this spot.”

This story in recent years has been cast into doubt by bloggers and historians alike who claim there is no official record of this ever happening.

Yet the story is told and retold, as it was in the Deseret News this week. It has been archived in Church publications for decades.

In fact, of all the records kept of the dedication of the Manti temple there is nothing to suggest that anything was “dedicated” before the temple was constructed.

Yet the story persists. Why?

Because it was put forward by Warren S. Snow, not the Church.

Historians have a bone or two to pick with Bishop Snow, Mayor Snow and General Snow, as he was known during his lifetime.

And yes – he is family.

He is one of the many illustrious sons of Gardner Snow, that grand patriarch of the Snow family.

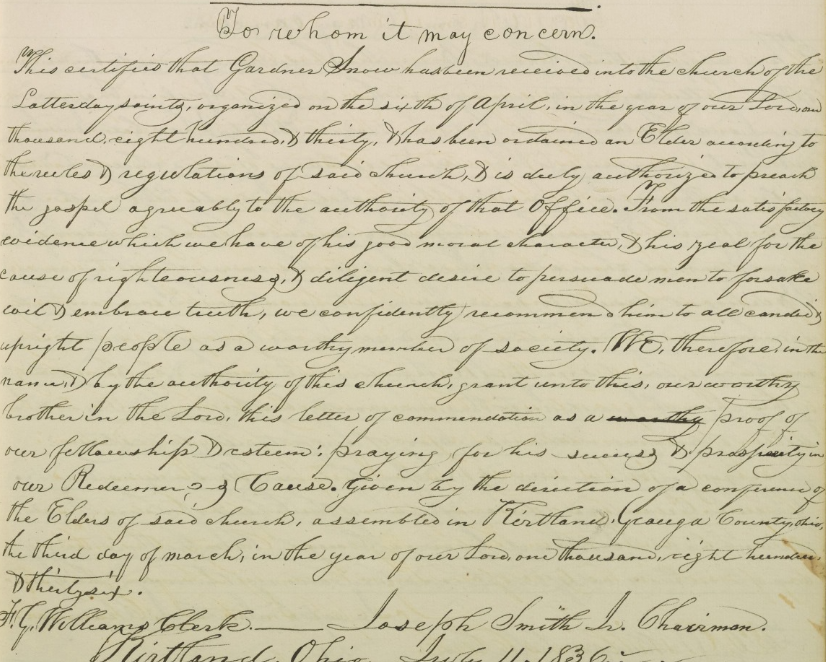

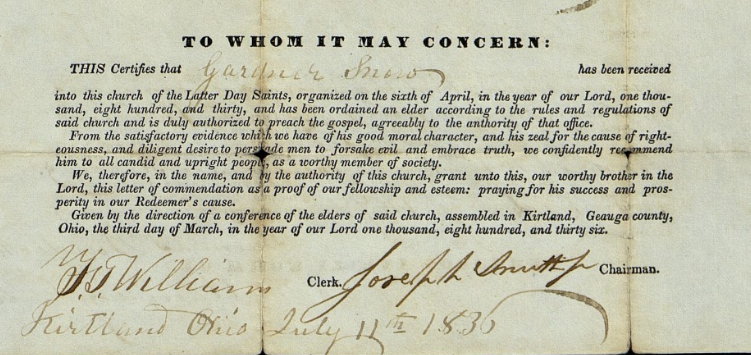

The Snow family started joining the Church in the very early 1830s, and their experiences in Vermont, Kirtland, Far West and later, Nauvoo, led to pioneering the West.

Warren S. Snow is just one part of multiple Snow family members who founded, lived, and played a part in establishing Manti, Utah. Manti, and the temple built there, would over the generations come to play a big part for the Westovers, the Smiths, the Snows, the Riggs and the Quilter families.

Manti has always been and likely will always be a very small and remote place. But it looms large as a home, a gathering place and a sacred ground for many we call family.

To fully understand how this came to be we need to tell some stories of those early Manti pioneers who helped to make that temple possible.

~ A Little Manti History ~

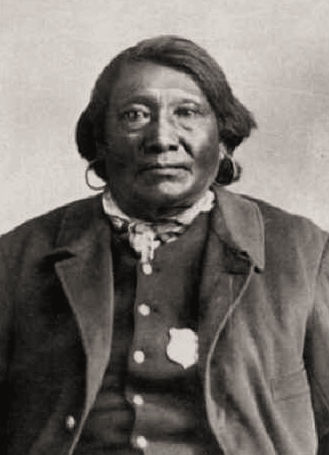

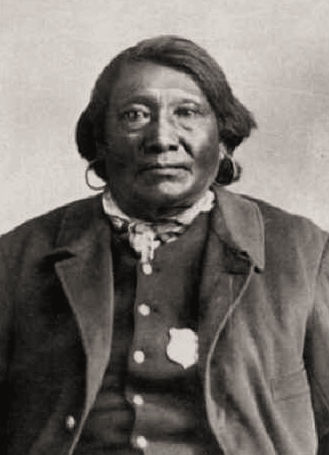

Chief Walkara, also known as Walker, was born about 1808, along the Spanish Fork River in what is now Utah, one of five sons of a chief of the Timpanogos band.

Described as being over six feet tall and extremely strong, he was a successful warrior from a young age. His piercing eyes earned him the nickname “Hawk of the Mountains.”

While there are plenty of stories about his life it must be noted that Wakara was known for both good and bad things. Some historians have called him the most prolific horse stealer in history. Others call him a great peacemaker.

What there is to know about historians, whether the speak of a man like Chief Wakara or a man like Warren Stone, is that historians usually have some point they are trying to make.

I personally believe that history is best told through those who passed through it. In the case of both Wakara and Snow, they left us plenty on their own to think about.

Around the year 1845, before white settlers came to Utah, Chief Wakara had a dream.

This is an account he told that was recorded by a Mormon settler later:

“He died and his spirit went to heaven. He saw the lord s sitting upon a throne dressed in white. The Lord told him he could not stay, he had to return. Walker desired to stay but the Lord told him that he had to return to earth that there would come to him a race of white people that would be his friends and he must treat them kindly.”

When the Mormons did come Chief Walker met in council, along with 12 of his warriors, with Brigham Young and church leaders in the Salt Lake Valley.

These Indians had come to ask Brigham Young to send colonists into the Sanpitch Valley to teach the Indians how to build homes and till the soil.

During the proceedings of this council which convened on June 14, 1849, at Salt Lake City, Walker remarked “I was always friendly with the Mormons. I hear what they say and remember it. It is good to live like the Mormons and their children. I do not care about the land, but I want the Mormons to go and settle it.”

A scout team was sent in August and by fall fifty families were called to go to the valley to settle it. It would be the first settlement south of Provo.

They were led by experienced men who names mark the pages of early Church history. Men like Isaac Morley, Charles Shumway, and our own great-grandfathers, Gardner Snow and Albert Smith, were sent.

Upon arriving many felt that the Sanpitch Valley was indeed a blessed place.

Father Morley, as most of the settlers referred to him, pointed a prophetic finger to a hill rising in the distance and said, “There is the termination of our journey; in close proximity to that hill, God willing, we will build our city there.”

That hill would come to be known as Temple Hill, in time. It was recognized as early as 1850 as a special place and some claimed visions while arriving there.

A woman named Betsy Bradley, and her three-year-old son, Hyrum, saw a personage in white on a white horse mysteriously appear on the hill and then, just as mysteriously, he disappeared.

Bradley told about this mysterious appearance to everyone who desired to listen and through it one of the Sagas of the Sanpitch was born: Everyone said, “This personage dressed in white on the white horse is the same personage that constrained Father Morley to proclaim it a special place and that person is the Prophet Moroni!”

Orson F. Whitney, in his book Life of Heber C. Kimball, relates this story:

“In an early day when President Young and party were making the location of the settlement here, President Heber C. Kimball, prophesied that the day would come when a temple would be built on this hill. Some disbelieved and doubted the possibility of even making a settlement here. Brother Kimball said, “Well, it will be so, and more than that the rock will be quarried from that hill to build it with, and some of the stone from that quarry will be taken to help complete the Salt Lake Temple.”

All of this was widely known long before Warren Snow and Brigham Young climbed that hill in April of 1877.

By that time, the history of Manti, of Warren Snow, of Brigham Young, of the Ute Indians, and of the temple had already covered a lot of ground.

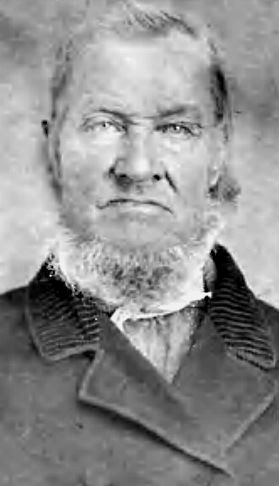

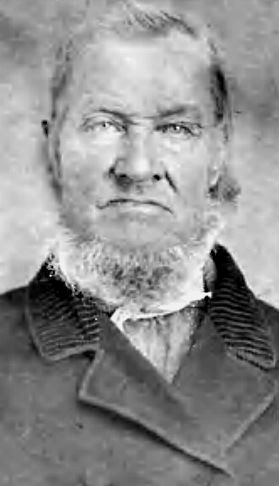

~ Gardner Snow, A Patriarch ~

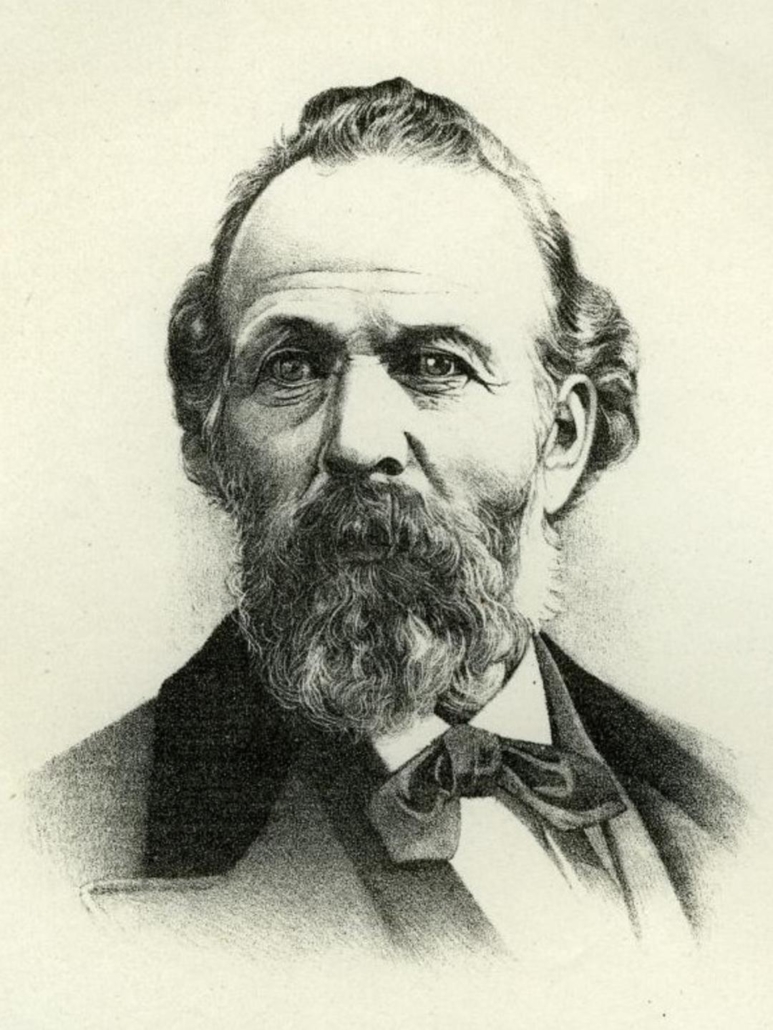

Gardner Snow moved to Manti in 1850, a little after the original parties led by his good friend Isaac Morley had selected Manti’s hill as the base for the community.

He was, at this point in his life, 57 years of age, an experienced veteran of the early LDS Church experience. He was seasoned. He had served as a missionary, Bishop, and a member of the Quorum of the Seventy.

He experienced the temple for the first time in Kirtland and later lived in Far West. He was chased, with many others, by mobs out of Missouri, and later had his home and possessions burned to the ground while living at Morley’s Settlement in Illinois.

In Nauvoo he received his temple endowments and later moved to Council Bluffs, where he resumed his work as Bishop.

When he was finally allowed to come to Utah he was assigned to Sanpete County, where he worked as a councilman and then later as a probate judge for many years.

By avocation, Gardner Snow was a sheepherder in Manti. He was in Manti less than a year when his partner, Sarah Sawyer Hastings Snow, passed away at the age of 60.

During their life together Gardner and Sarah had 9 children – six of them sons. Of those six sons only three survived into extended maturity.

James Chauncey Snow (our great grandfather), like his father, had experience in early Church history and came around the same time as his father to Utah. He would be a Stake President in Provo and live a long life of family and church service.

Warren Stone Snow, who you will read more about below, would become a Presiding Bishop in Utah and a controversial figure in the history of Manti.

George Washington Snow came with his brothers to Utah in the early 1850s, settling near their father in Manti. He would work for some years as a cooper in Manti, where he also studied the law and later served as a lawyer, the prosecutor of Sanpete County and in various elected public roles for years.

All of these Snow men were deeply embedded in Church and public service in Central Utah.

Their histories are all public record. In their various fields of service they touched the lives and many and were known by generations of Manti citizens.

Gardner Snow was especially well thought of, much like his friend Isaac Morley, because they were early church members who knew the Prophet and had experienced the persecutions of the early Church experience.

All of these men would die before connections with the Westover, Smith, Riggs and Quilter families were made.

It is curious to contemplate how their passions for the temple and getting it completed in Manti during their lifetimes would come to be meaningful for their later descendants.

~ Albert Smith in Manti ~

Albert Smith’s connection to the Westover family comes through is granddaughter, Mary Ann Smith, who married my great-grandfather, Arnold Westover.

If there is any individual representative of the 19th century Mormon experience, it is Albert Smith.

He joined the Church in 1835, lived in Missouri and Western Illinois, suffering from the persecution and loss of those places before the Nauvoo period.

Like many others, he relocated to Nauvoo and was in the same ward as Joseph Smith – in fact, he knew the Prophet well.

Albert was friends with several individuals known in Church history, notably Wilford Woodruff, and he would, in time, become acquainted with others who played important roles in pioneering Manti.

While living in Nauvoo, Albert served a mission, returned home to find his family in crisis due to the scandals of John C. Bennett, and he helped to construct the Nauvoo temple.

Albert and his family were among the first company to leave Nauvoo and was at Mt. Pisgah when Brigham Young called for service in the Mormon Battalion.

Albert served, along with his 17-year-old son, Azariah, the entire year. They backtracked to Utah from California, arriving just after the Saints first got there in the summer of 1847.

He farmed his allotted acreage in the Salt Lake Valley, and it was on his land that the miracle of the seagulls took place, an event he recorded in detail in his journal.

With many others Albert and family were called to move to Sanpete County.

Albert and his wife established a farm and used their home for the first several years to host the first dramatic productions held in Manti. They were very involved in the community and Albert dutifully recorded it all in his journals.

For all his Mormon experience and his faithfulness, Albert never held high position in the LDS Church. In time he would embrace plural marriage, albeit reluctantly.

For more than 40 years Albert steadfastly built the Kingdom of his faith, commenting here and there in his journal of both his experiences and his opinions of the pioneer experience.

The Manti temple, for him, represented many things.

What he would do over the forty years it took to build that temple in Manti should be an inspiration for all of us who call ourselves his grandchildren.

His quiet, in-the-background life of service stands in contrast to a man he would share family with in the generations to come.

That man’s name is Warren Stone Snow.

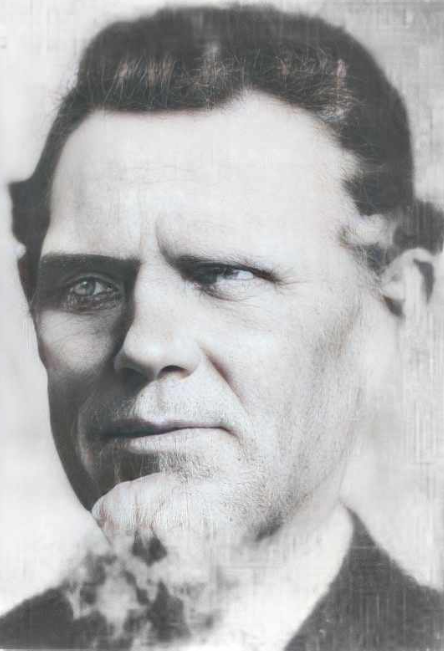

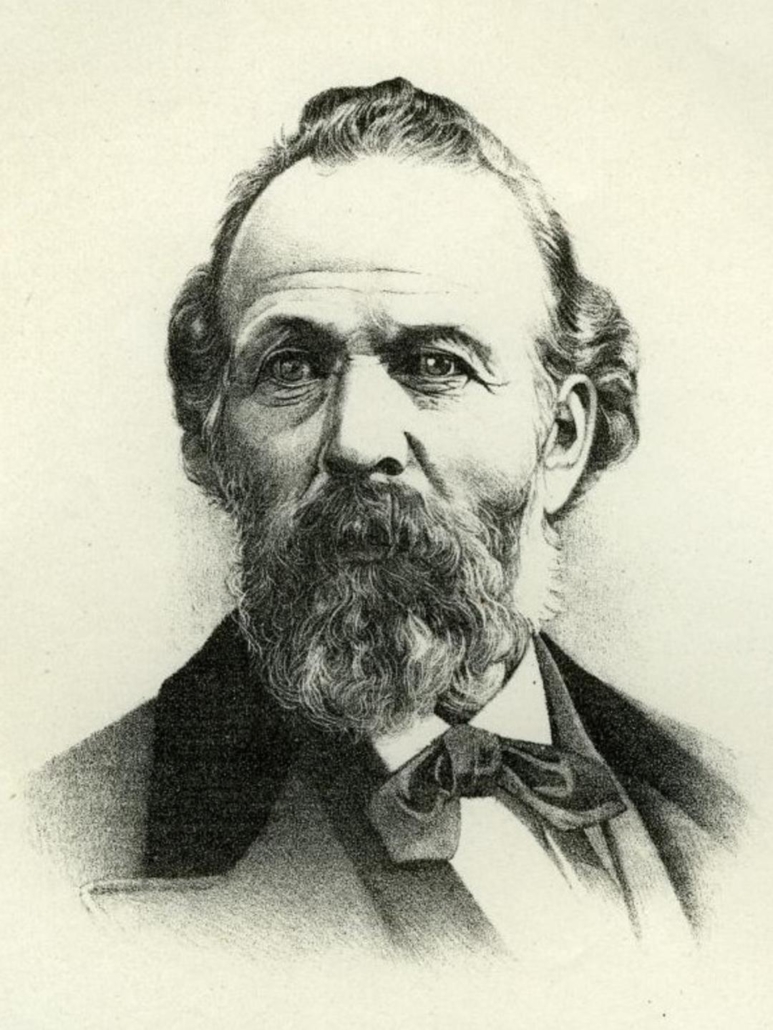

~ Warren S. Snow – A Complicated Man ~

The Snow family of Manti has a long history in the LDS faith.

In fact, they were one of the most unique families in early church history with the likes of Lorenzo Snow, Eliza R. Snow, Erastus Snow, Gardner Snow, James Chauncey Snow and Warren S. Snow among their famous numbers.

Their history and exploits as a family during the rise of the Church in the 19th century was so great that one Congressman, Charles B. Landis, in a speech made in 1900, declared the Snow family “the most consistent Mormons in the whole bunch”.

But Warren S. Snow was different from his famous father, brothers and cousins.

His foundation of faith was indeed built in his youth while attending early church gatherings in the Mormon Barn, as it was called, of his grandfather, Levi Snow, in Chesterfield, Vermont.

But his experiences as a young man serving in security capacities for the Church seeded a conflict within him that colored nearly all of his later experiences as a church leader.

He was there – and close to the Prophet Joseph Smith and his family – when the Prophet was murdered in 1844.

In fact, in recorded talks given in church conferences not long after the Martyrdom, Warren referred to the bodies as “mangled”. It was an event that traumatized him so greatly that he often spoke strongly, if not violently, against the enemies of the Church.

Warren’s long service in the conflicts that arose during the post-Nauvoo period later left him described as a chosen defender of the Church and its prophets. He would, in time, enter into the circle of Brigham Young and become his close friend.

Brigham at one time considered Warren S. Snow as a potential member of the Quorum of the Twelve, saying that he was a “good man” when his name was brought up in counsels.

As it was, Warren S. Snow was assigned to Manti and made the presiding Bishop there, as well as a leading representative in the territorial legislature. In these capacities Warren had vast responsibilities related to church and civic governance.

He was consulted on how and where new settlements would be established and he placed men in important positions in Church leadership all over central Utah. He reported directly to Brigham and the Quorum of the Twelve and met with them frequently.

But there were troubled episodes during the early church leadership service of Warren Snow.

During a brief period after the Utah War, an examination of tithing funds in Manti resulted in a scandal made public from the pulpit by a visiting apostle, Orson Hyde, who declared Warren’s leadership suspect.

After a long and humiliating public investigation, it was determined that the bishopric led by Warren Snow was “careless” instead of dishonest.

Warren Snow publicly repented of his part in the scandal and that repentance was accepted by his superiors who had stood critical of him. But the event did great damage to his reputation and Warren struggled to regain the respect of the people of Manti.

His reputation as a hard man had proceeded him, and many questioned his judgment given the rumors they had heard about him over the years.

During the passionate period known as the Mormon Reformation, a time when “hellfire and damnation” was preached from the pulpit as leaders browbeat the Saints for not living their religion, Warren Snow was among the most vociferous.

His sermons from the time accused Church members of the need to repent and do better against all kinds of weaknesses and shortcomings.

During this period Warren was viewed as a particularly harsh leader. Some of his actions in his callings did little to dissuade the skeptical nature of how others viewed him.

In one famous episode the case of a man who was guilty of serious sexual transgression was brought before a Church court led by Bishop Snow. Excommunicating the man was not strong enough for members of the council – or for Bishop Snow.

In a clandestine midnight mugging of the man he was castrated, evidently at the hands of the Bishop and those members of the council who had excommunicated him.

Word of this reached Brigham Young and other Church leaders and another investigation ensued, casting a cloud of suspicion over Warren Snow that he never fully recovered from.

Part of the suspicion of Bishop Snow came from his reputation as a Church defender.

During the Utah War Warren Snow was a commanding general in the Nauvoo Legion, the holdover militia organized in Utah to defend against invading forces.

Snow was specifically charged by Brigham Young not to kill the troops on the way. He could steal cattle and supplies, set fires, and do anything possible to disrupt their march to Utah but he was not to engage in the use of deadly force.

Surviving records of the campaign indicate this was a difficult charge for Warren Snow, who wanted revenge on the enemies of the Church.

In Church talks Warren Snow often spoke of defending the faith.

A patriarchal blessing given to him sharpened his self-view in this role. It told him he was called to the protective service to the Church and promised that he could not be killed by enemies of the faith.

But for all of Warren’s passion about defending the faith there was another side to him that was markedly compassionate and spiritual.

He was blessed with a number of spiritual experiences that profoundly influenced him, including hearing the voice of God during the dedication of the Kirkland temple and witnessing the transfiguration of Brigham Young.

In the early 1860s, perhaps in a move to rescue Warren Snow from his reputation, Brigham Young sent the Bishop to England on a mission.

He served for several years with distinction and surviving letters between Warren and Brigham show that Warren did all he could to re-establish good feeling between them.

When Warren returned Brigham did welcome him with open arms and he sent the same apostle, Orson Hyde, who had led the investigation against him years before, to address the people to proclaim Warren’s innocence and to re-establish him in local church leadership in Manti once again.

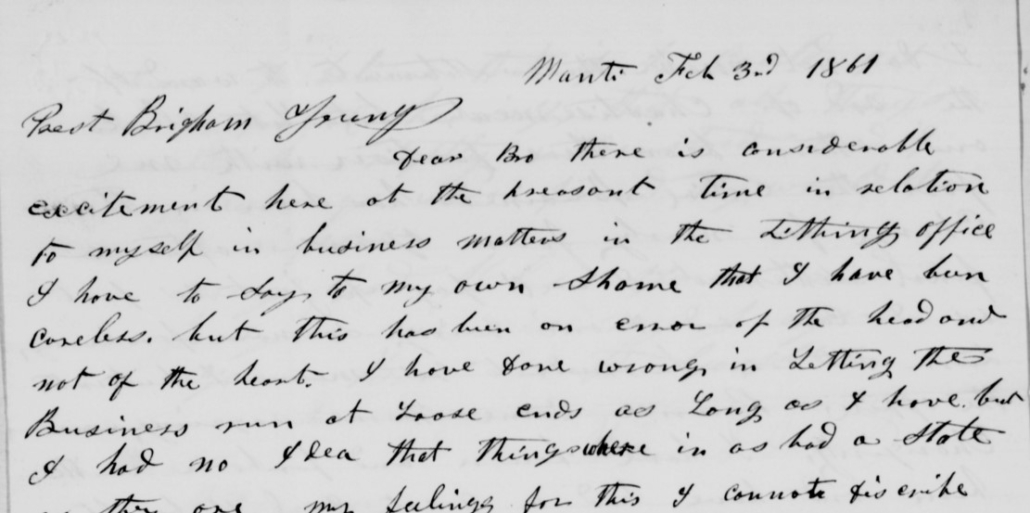

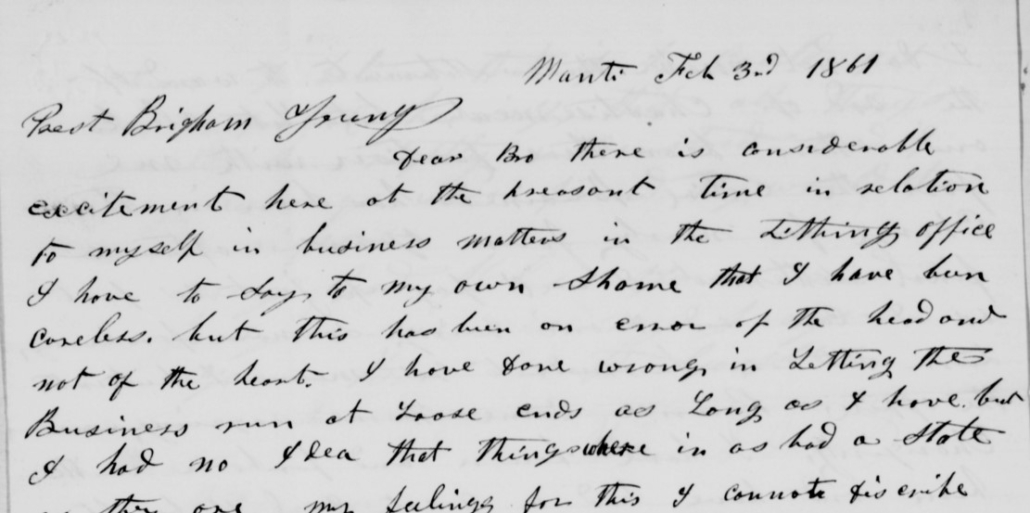

A letter from Warren Snow to Brigham Young. Source: Church History Library

It did not go well for a time. But before long Indian uprisings created a need for Warren Snow, Defender of the Faith.

For years the residents in Central Utah had endured constant badgering by roving bands of Indians who would steal cattle and occasionally kill settlers.

Brigham’s strategy statewide for the longest time was to appease the Native Americans who lived there, clinging to the idea that he would “rather feed them then fight them”.

But not all settlers had Brigham’s patience.

When property was destroyed and especially when lives were taken many felt to impose an equal loss upon the Indians.

This inflamed situations over and over, and after a particularly gruesome killing of white settlers up a nearby canyon, things quickly got out of hand with a young Indian leader known as Black Hawk (a nephew to Chief Walker and a son of Chief Sanpitch).

The more the back-and-forth of killing between the Indians and the whites happened the bigger it seemed that Black Hawk’s band grew. In short time, greater damage and increased numbers of people were killed on both sides.

When the appointed leader of the local militia abandoned his post in the middle of a conflict it was Warren Snow who assumed command.

Working as closely with Brigham Young as he could Warren saw this new opportunity to prove to the community of Manti that he was a changed man.

For more than a year the Black Hawk War, as it came to be called, raged as Warren and Brigham tried to bring peace through restraint.

While Warren Snow was plain spoken with Brigham Young and other Church leaders about what he thought should be done he always sided publicly with what Young both advised and publicly said.

But Black Hawk persisted, and the event escalated after Warren Snow had promised safety for Indian warriors only to have more of them killed by restless settlers bent on revenge.

Everyone was aware of how tenuous the situation was – even Albert Smith.

From his journal we hear of an uprising that started in Gunnison, where a Mormon family was brutally murdered by marauding Indians.

The retaliation event took place right in front of the Smith home in Manti, as local settlers there captured two Indians completely unconnected with the Gunnison affair and tried to kill them.

Albert intervened and pled for their lives, stating to his fellow citizens of Manti that killing the wandering pair would only lead to more bloodshed on their own properties and to their own families.

He echoed, perhaps unknowingly, the same sentiments advanced by Brigham Young and Warren Snow.

As had happened so many times before, Albert’s admonition was ignored. For months the people in Manti went into hiding for fear of Indian retaliation.

In time, both Brigham and Warren came to see that something needed to be done to get Black Hawk to back down. Over the course of 9 months Warren led large groups of men in attacking and capturing leaders of the Indian band.

The Indians stepped up their part by using women and children to help captured prisoners to escape and on one careless night at the jail in Manti, Utah they caused the escape of about 8 Indian warriors.

Warren and his men gave chase and during a very close exchange of gunfire on the streets of Manti, Warren killed two Indian chiefs while sustaining a bullet wound to his arm and shoulder.

He wrote to Brigham to report on the affair, expressing regret at having to take a life to save his own.

Knowing that the event would inflame things even further, Brigham sent Warren on a relentless chase into the Fish Lake forest in search of Black Hawk and his closest men. It took months, and Warren ended up with greater wounds and became exhausted from the chase.

His exploits were reported in the news and in time the campaign began to wear down Black Hawk and his men. Black Hawk went on record to say that as long as Warren Snow lived in Manti he would never know peace.

Brigham felt that maybe Warren Snow, for as valiant as his efforts had been, could have been making things worse with Black Hawk. Seeing that Warren was injured, exhausted, and leaving the care of his family to others for long stretches of time, Brigham relieved him of command and sent him home to heal.

The change in leadership did help in ending the conflict with Black Hawk. In months, hostilities ended.

But the whole affair had a restorative effect on Warren Snow’s reputation. He returned to cheers in the streets of Manti and in time became Mayor of the city.

His service as a church leader in the years that followed were markedly different this time around.

For the next 30-years Warren Snow enjoyed a reputation as a man of prudence, a man of compassion and a man who defended the faith with softer tones and greater testimony.

So, when Warren Snow stood on Temple Hill in Manti with Brigham Young and later declared that President Young had said Moroni had dedicated that spot for a temple in the Latter-days, people took him seriously.

In fact, his funeral in 1896 was attended by thousands of people. His impact on the community and the whole of central Utah would go down in local history in glowing terms.

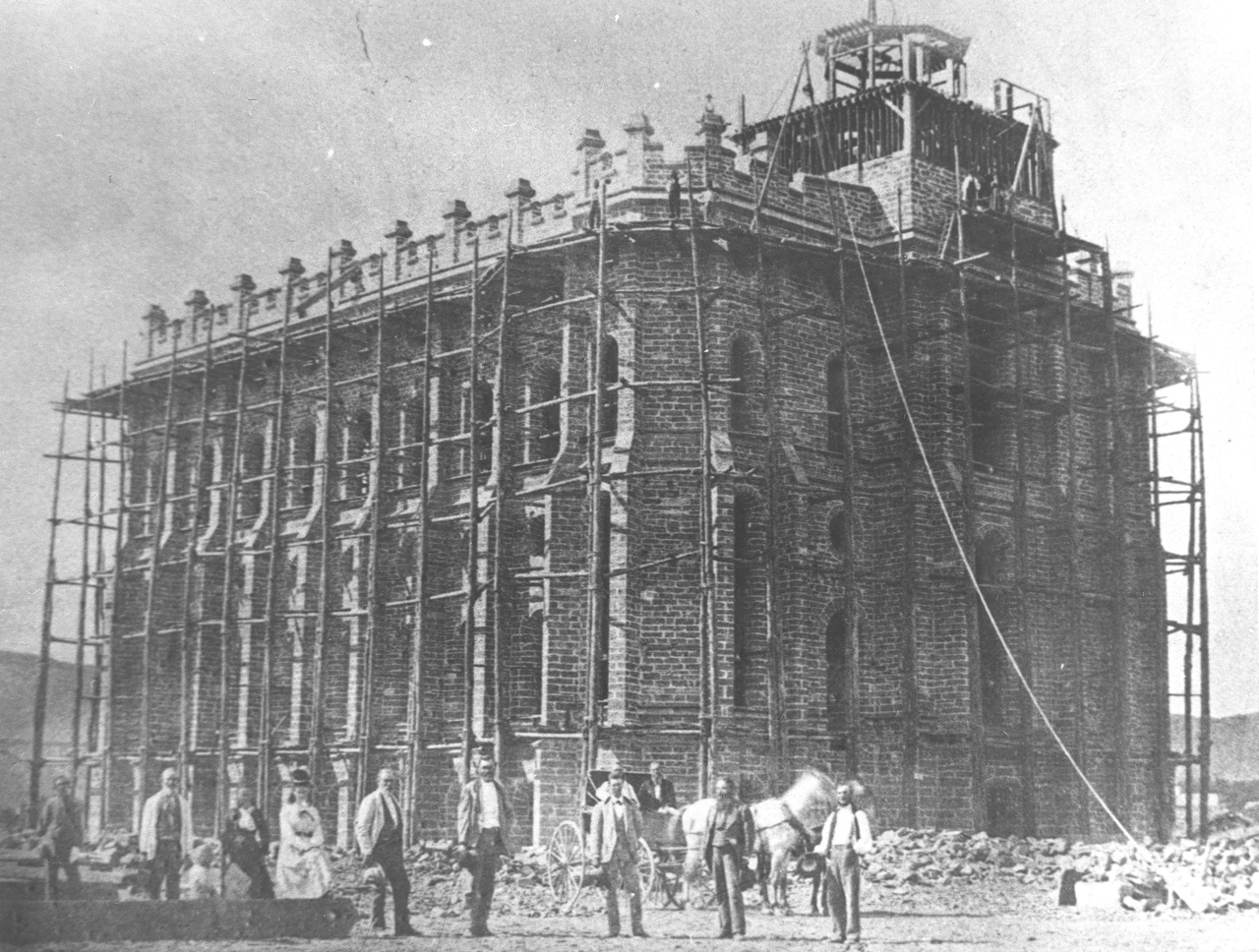

The Manti Temple, which was announced in 1875, featured a variety of events that involved the entirety of the community.

A parade was held when the ground was dedicated (or, rededicated, if you will). The Mormon hierarchy present included the First Presidency, members of the Quorum of the Twelve, and prominent local citizens such as Patriarch Garner Snow, and, of course, General Snow.

The Monday following the dedication of the site, on April 30th, 1877, the citizens of Manti gathered for a groundbreaking ceremony so that work could commence that day.

The 100-people gathered knelt in prayer led by Bishop John B. Maiben, then Partriarch Gardner Snow prayed over the labors.

One by one the prominent individuals of Manti took their turn with the shovels in the following order: Bishop Maiben, Patriarch Snow, James Wareham, Hans Jensen, Frederick Cox, Albert Smith, Jezreel Showemaker, George Peacock, Luther Tuttle, and George Billings.

After these ceremonial few, more than 80 men with their horses and oxen began the broad work of excavating with plows, scrapers, picks, and shovels. It would be the first day of more than 11 years of temple construction.

For Albert Smith, who attended these events and noted them in his journal, the coming of the temple spurred an effort to do his family history.

He wrote letters and sent money to genealogists in New York and Massachusetts. This happened before the temple was first announced in 1875.

Along with his third wife, Grandmother Sophia Smith, the anticipation of the temple was something recorded with each passing season. Albert and Sophie would visit the unfinished temple frequently and record what they saw.

By the time the temple was completed in 1888 Albert had possession of nearly 2000 names of his ancestors. He was proud of his Mayflower connections and was anxious to get into the temple to do work for them.

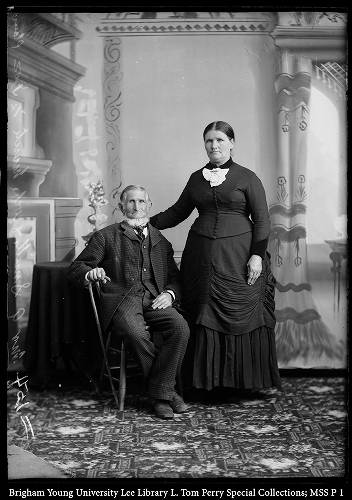

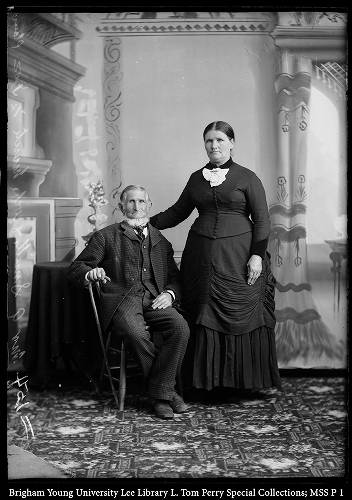

The temple dedication was an event so anticipated it is believed that was when this notable image of Albert and Sophie was taken:

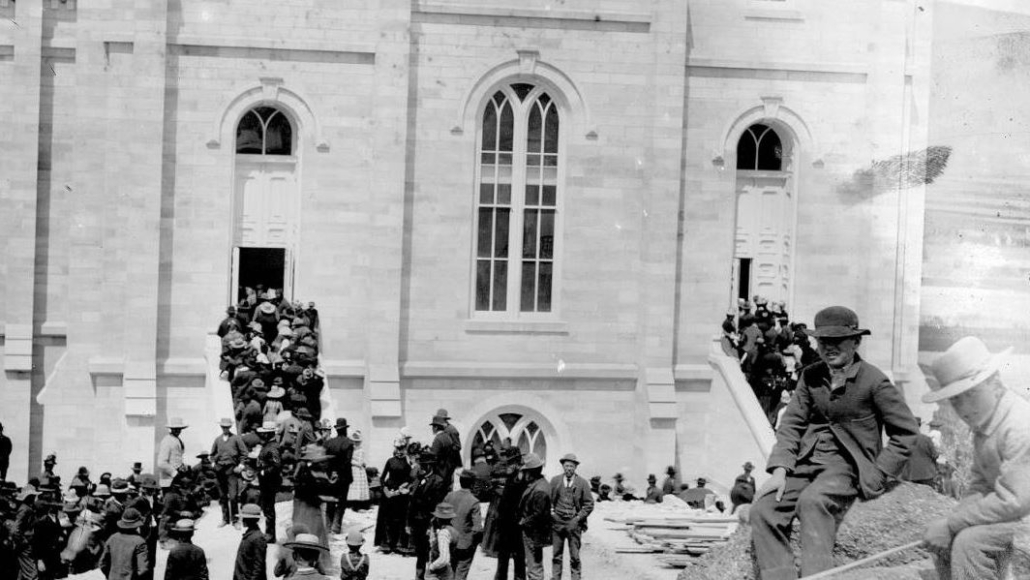

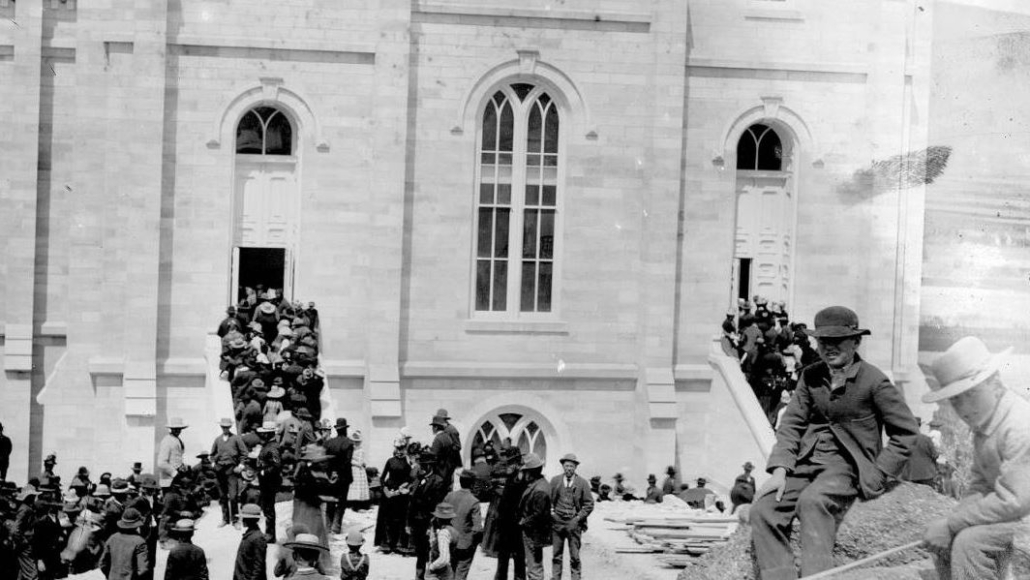

When it finally came time to dedicate the temple more than 5000 people came to the remote location of Manti to participate.

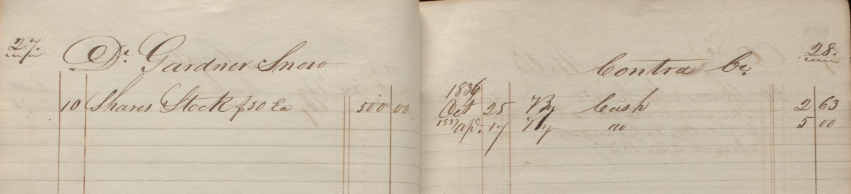

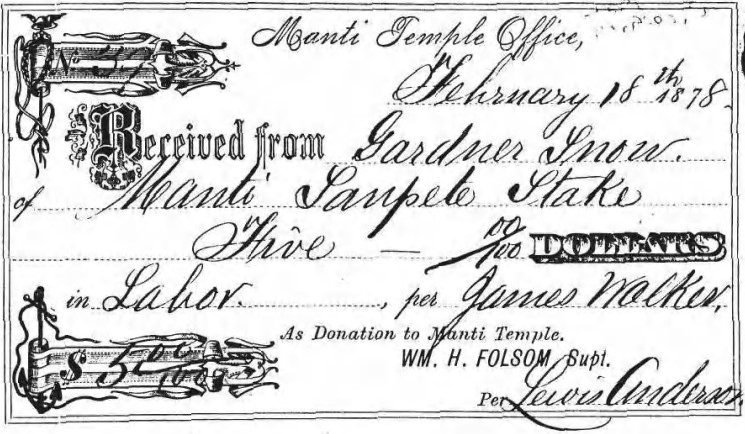

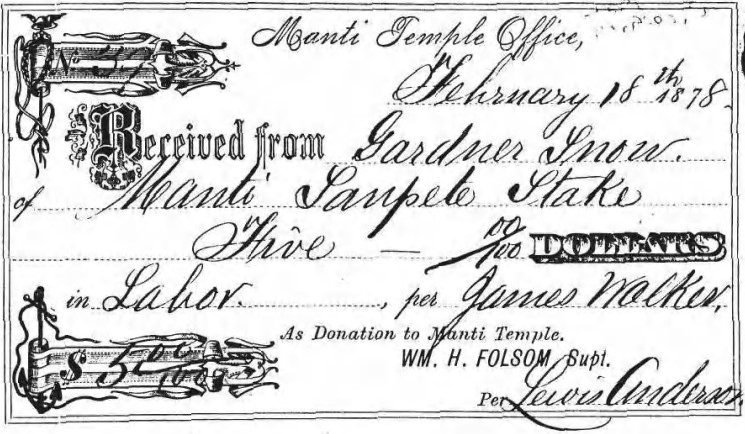

Going to these events required tickets or invitations. In fact, nearly everything associated with the Temple over the years of it’s construction featured some sort of documentation. Here is a donation slip showing a contribution made by Gardner Snow:

Albert himself did not get tickets to the first day of dedication events. He watched the assembled masses at the temple from his front porch and attended for himself on the 2nd day.

Crowds at the Manti Temple dedication

~ What Temples Meant to the Pioneers ~

The pioneer era temples – which include both Kirtland and Nauvoo, by the way – were built during seasons of duress. They were built despite the poverty of Church members. Each was a tremendous act of faith.

As such, the completion of each temple was a celebration of faith. Within the temples the Saints could worship in the most sacred ways.

Simply put, a temple dedication was a big deal.

When Saint George was completed in 1877 as the first temple in the West, nearly all of those living in Manti, including the Snow and the Smith families, traveled to participate.

For years prior to its completion the Saints in Sanpete sent money and materials to St. George to help with the temple. After the St. George Temple was completed the members of the Church there returned the favor to assist in building the Manti temple.

For these pioneer temple builders the Temples provided a place for their children to make covenants and to be “sealed” together.

Perhaps the first of the next generation of the family to take advantage of the new Manti Temple was Joseph Homer Snow, son of James C. Snow. On July 19, 1888, just a few months after the dedication of the Manti Temple, he was sealed to Mary Nielsen, who went to the temple for herself for the first time on that date that they were married.

Joseph and Mary Snow would go on to have ten children. Their fourth, a girl they named Muriel, was born in 1891. In 1913, Muriel Snow would go to the Manti Temple and marry William Reeves Riggs, Jr.

They had a large family too. Their 2nd child, a daughter named Maurine, went to the Manti Temple in 1940 – and there married Leon Westover.

Maurine was following in the steps of her sister, Milda. Who only months before, in June 1940, went to the Manti Temple and married Charles Gerald Quilter.

Of course, there were other marriages and other temples in different places. That is not the point.

The point is that generations after the pioneer era temples were built the children and grandchildren of those pioneers who built them took advantage of them, fulfilling prophecy, fulfilling dreams and bringing forth new generations “born under the covenant”.

Was this what Moroni, the last of his ancient people, was thinking if he was indeed seen in vision in Manti?

Who exactly was Moroni and what could be his connection to Manti?

For members of the Church, we know that Moroni appeared to Joseph Smith in 1823 to extend to him his calling. During that event, the Prophet Joseph recorded that Moroni quoted from the Biblical book of Malachi, stating, in part:

“…And he shall plant in the hearts of the children the promises made to the father, and the hearts of the children shall turn to the fathers. If it were not so, the whole earth would be wasted at his coming…”

This, and other things given to Joseph Smith as Moroni taught him over the next several years, laid the foundation for modern temples as part of the “restoration of all things”.

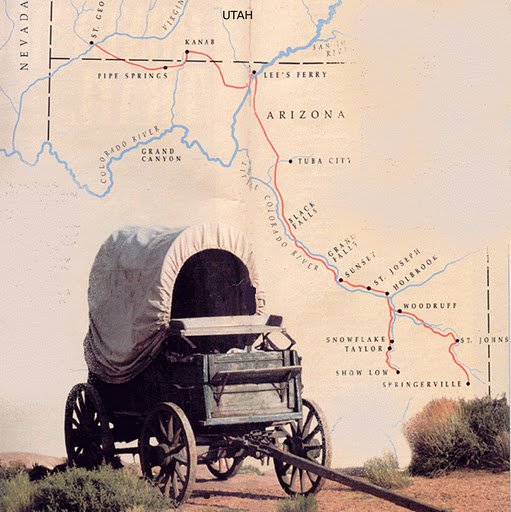

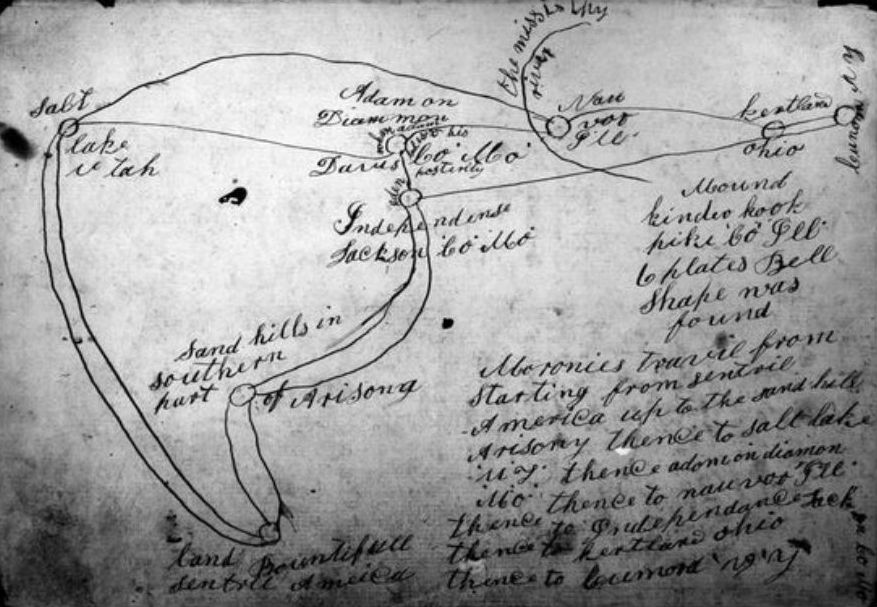

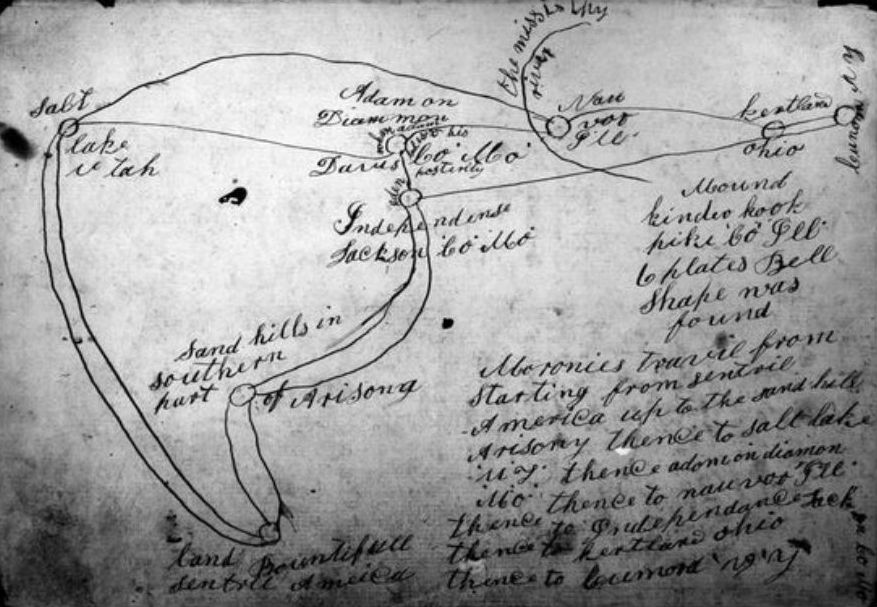

Joseph Smith spoke of Moroni several times during his lifetime and offered information not contained within the Book of Mormon about him. Associates of the Prophet recorded such conversations and from those memories came this map outlining the travels of Moroni in North America:

Researchers now conclude that Moroni may have not only dedicated the land where the Manti temple now stands but that he could well have done similarly in St. George, Nauvoo, Independence, Kirtland and “others we know not of yet”.

This research was not conducted before the time of the pioneer era in Manti. It was not information that was widely shared or known.

Is it merely coincidental then that Warren Snow and other such as Betsy Bradley shared what they knew of Moroni in Manti?

That is speculation of a spiritual scope left for greater minds than my own.

All I can say, as one living in the 21st century, attending a temple and reflecting on my pioneer temple heritage, and as one now anticipating a new temple dedication in the years ahead where I live in my stake in Smithfield, Utah, is that I have no doubt of Moroni’s connection.

No, like Albert Smith, I lay no claim to visions.

I take on faith that the gift of such given to others is theirs.

The gift given to me to know is that God is in command and we know that best through work done in temples, where my heart is indeed knit with theirs and the covenants they made with God.

Alexander and Electa Westover had four children while building their farm in Ohio and three of them lived to adulthood: Edwin, Charles and Oscar.

Alexander and Electa Westover had four children while building their farm in Ohio and three of them lived to adulthood: Edwin, Charles and Oscar.