The Honeymoon Trail

/

0 Comments

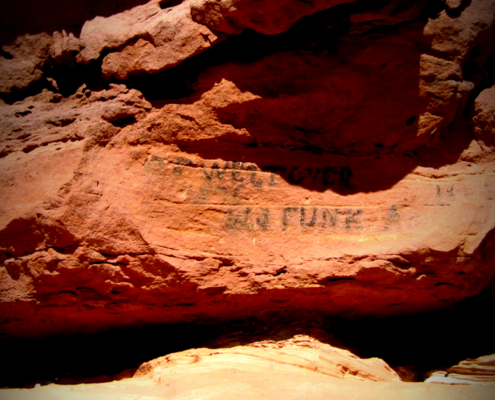

Just west of a place out in the middle of nowhere on the Utah/Arizona…

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/kirtland.png

628

1200

Jeff Westover

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/logo22.png

Jeff Westover2024-03-05 16:08:282024-03-05 16:08:28Kirtland Connections

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/kirtland.png

628

1200

Jeff Westover

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/logo22.png

Jeff Westover2024-03-05 16:08:282024-03-05 16:08:28Kirtland Connections

Family History vs Family Story

Of all the projects at the end of Dad’s life nothing was more…

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/decisions.png

628

1200

Jeff Westover

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/logo22.png

Jeff Westover2024-02-24 13:45:272024-03-03 16:22:44Decisions and Consequences

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/decisions.png

628

1200

Jeff Westover

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/logo22.png

Jeff Westover2024-02-24 13:45:272024-03-03 16:22:44Decisions and Consequences

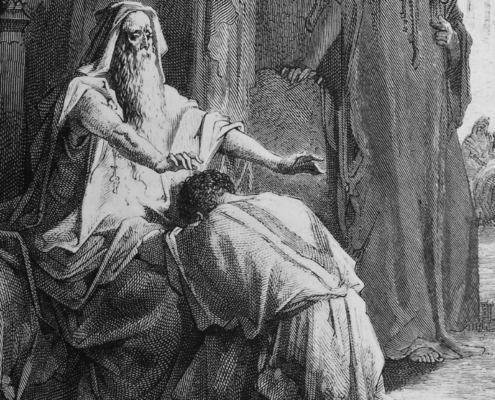

The Blessings of Patriarchal Blessings

Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints can…