The History of Winifred Calista Welty

Winifred Calista Welty was born in 1917.

Her brief life of 49 years is not marked with notable worldly accomplishments. She had one child, my mother, Susanne Catherine Begich Westover.

Grandmothers usually play a vital role in the lives of the rising generation. Winnifred certainly made her mark in influencing her Westover grandchildren.

As her grandson this is my attempt to share her story as I understand it. I make no claim that this is comprehensive or complete. I include details shared with me by my parents and extended family members who knew her. Sadly much has been lost to time and circumstance and there are many questions I cannot answer.

Hers was a complicated and tragic life. It seems a bit unfair to see so much heaped on the shoulders of one person.

Winifred’s trials and isolation from family complicated her situation and, as a result, my Mother’s situation as well.

It is a story of long reaching consequences. It is a tale of strange arrangements, sad realities, and difficult facts. It is one that would affect many relationships over several branches of the overall family for generations. As such we must share the aftereffects of decisions made during Winnie’s life and include some memories of some still living, including experiences of my own.

In so doing we take some risks.

Family history is sometimes difficult to recount because there are often different sides to the same story that do not get represented. In this case, some have passed on and can no longer speak. I acknowledge that new information may later surface or different details could later be shared.

The lessons learned are not only important for those who love Winnifred Calista Welty. They are vital in uniting cousins of rising generations and keeping the family connected over events long past that we can do nothing about.

This is a story of deep feelings, mistrust, misunderstanding, tender isolation and of overcoming through love. It includes elements of abuse, deep loss, and forgiveness. In the end, miracles are also part of the difficult details.

This is Winifred’s history.

As with us all, it begins long before her birth.

~ Welty Family Origins ~

When Johan Jacob Welty arrived in America via the immigrant ship, the Ketty, in 1752 he had with him his bride, Christina. They would join a community of fellow German immigrants in an established German community in Dover, Pennsylvania. He was 42 years old.

Dover was a great place to grow things. The Germans there brought their agricultural traditions, their schools, and their churches with them. Johan – known by the American-English name, John – would farm and raise a family of six children with Christina.

A son, named Phillip Jacob Welty, would be born in Dover in 1759.

Phillip married Anna Maria Wilt around 1780 and they worked the family farm in Dover and raised four children there. Their eldest child, a son they named Jacob, was born in 1781.

Jacob Welty became the third generation of the family to take over the farm in Dover. He met a local girl named Barbara and married her around the year 1808. They would have seven children, including their third, a son, who they also named Jacob.

This Jacob Welty would continue the family traditions of farming. But after marrying Elizabeth Krigbaum in 1837 they would venture about 200 miles north to the new farming community of Lindley, New York – becoming one of the first settlers in that area.

Jacob and Elizabeth would raise a family of nine children, many of whom lived well into the 20th century. Among their number was a son they named George – an old Welty family name from Germany – who would spend the entirety of his life in Lindley.

George Welty, who was around 18 years old at the time of the Civil War, likely served in the Yankee Army. He married as the Civil War ended in 1865, having survived the entirety of the war. His bride, Maria Sarah Weldon, was the daughter of Harvey and Betsey Weldon, prominent local citizens with a long family history in southwestern New York state.

George and Maria raised eight children and, like the five previous generations of the Welty family, they taught them all to farm. But their youngest son, named Alfred, born in 1893, was no farmer.

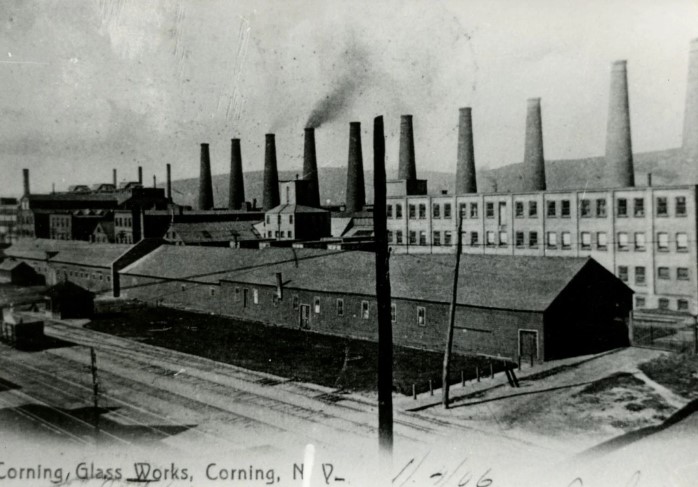

Alfred, as an adult, was one of the few Welty sons who did not continue the tradition of farming. He took a job in the near-by community of Corning, at the Corning Glass Works, as a glass gatherer.

~ Alfred and Susan ~

It is believed the Carson family came from Ireland around the 1820s. John Carson, a son of Samuel and Mary Carson, likely came to the United States as a child. He married Elizabeth Hyatt around the year 1825 and with her would raise a family of six children.

Their second son, named Erastus Carson, was born around 1830 and would serve in the Civil War in the 1st Cavalry Regiment, nicknamed the Lincoln Cavalry, from 1861 to 1865. Injured in some way during the war, he returned home and married Elizabeth Coolbaugh, in 1872.

Their second child, a son they named Kit, was born in 1876. Kit was raised a farmer and is mentioned in local newspapers over the course of his lifetime for his achievements and community involvement. Kit married Effie Groom and they raised a large family of twelve children. Their eldest, a daughter they called Susie, was born in 1898 in Corning, New York.

At some point Alfred Welty and Susie Carson met.

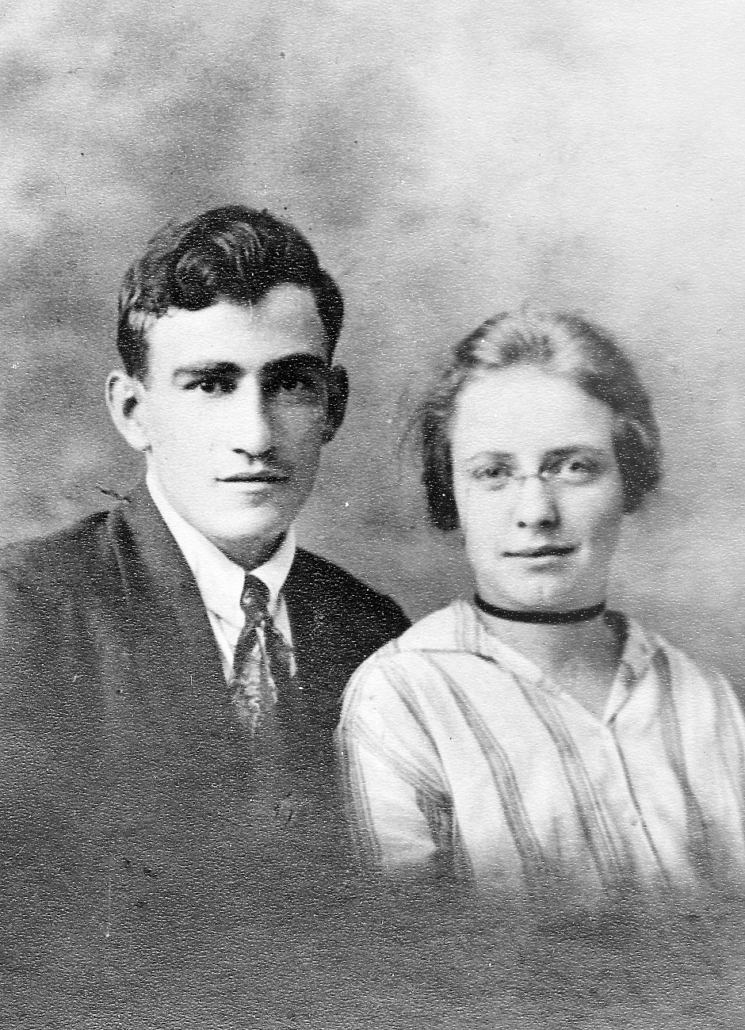

They married, in Corning, on November 24th, 1916. Susan Catherine Carson was 18 years old. Alfred was 23.

Alfred and Susan’s Wedding photo

On April 25, 1917, their first child, a daughter, was born. They named her Winnifred Calista Welty and called her Winnie. The next year, on November 8th, 1918, another child, a son they named Norman Francis Welty, was born.

~ Troubles and Tragedy ~

Alfred and Susan’s wedding was a well-attended family affair held at the home of Kit and Effie Carson. The world was already embroiled in World War I and forces were galvanizing in the US at the time of the wedding.

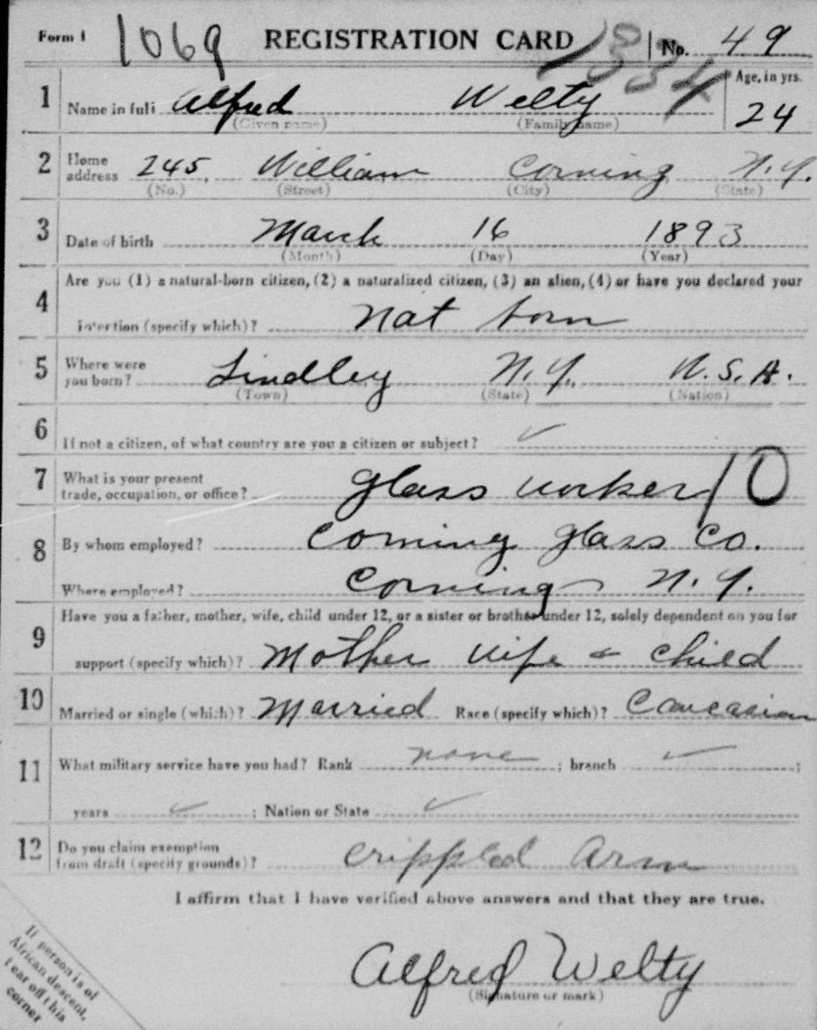

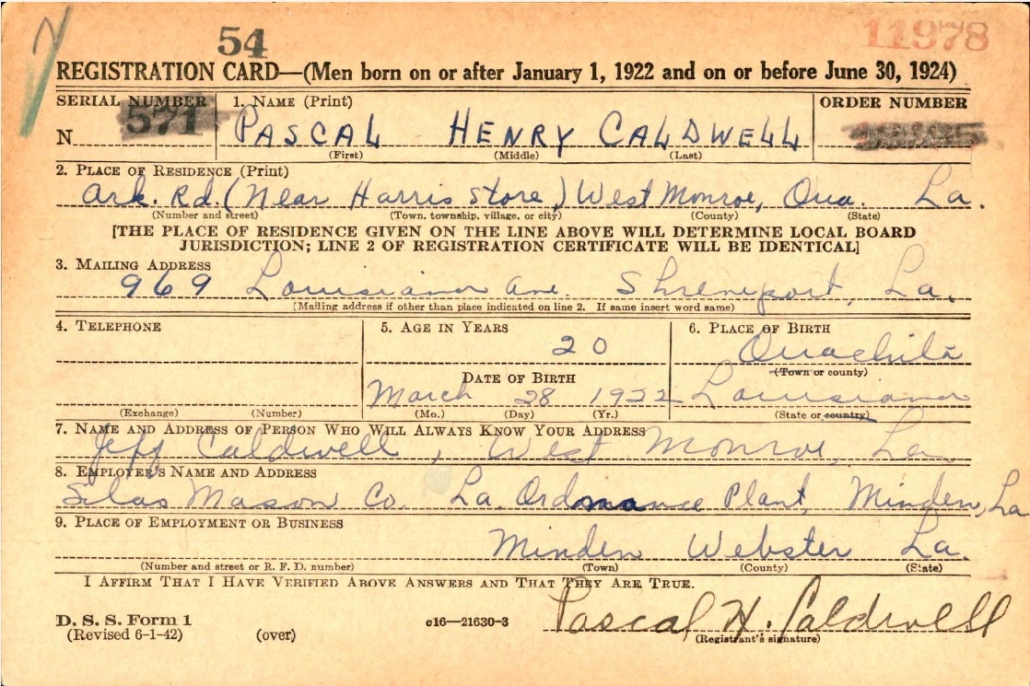

Alfred, being of age and unmarried, was exempted from the draft. His draft registration clearly shows he had a handicap in a crippled arm. It is not known if this was the result of a birth defect or of some injury:

The Welty family had some military experience. Alfred’s father, George, as noted above, served. George’s younger brother, William, born in 1843, is on record enlisted in the 107th infantry.

In investigating the other Welty family members of service age during the Civil War two things stand out: nearly all served and many suffered significant aftereffects of that service.

Some of the same can be said of the Carson family as well, although evidence suggests not quite as many Carson family members served in the war. The Civil War was a game changer in many ways for most. For the Yankee residents of New York state the war was long and terrible. Hardly any family was unaffected.

For George Welty and his bride, Maria, growing their family on the rural landscape of Lindley, New York carried on the traditions of earlier generations. Surviving records show a family striving to endure the rigors of farm life. George would appear in the news for having suffered a broken leg due to a chain that broke while trying to remove trees. When George’s father, Jacob, died in 1900 it was George who administered the estate and officially inherited the farm he had long worked.

Alfred Welty was born in 1893 when his father, George, was 52 years old. In census records of the 1890s and early 1900s Alfred was shown as a farmer rather than as a student. Local newspapers often noted the workings of the Welty farm and the travels of George Welty who continued to work it well into his 70s.

Alfred did attend school as a child. But better than 20 years separated Alfred from his two eldest brothers. Alfred left after as his father died in 1913 – the family farm by then likely fell to one of his older brothers. Alfred took up residence in the nearby biggest city of Corning, New York – home to Corning Glassworks.

It is unknown how Alfred and Susan met.

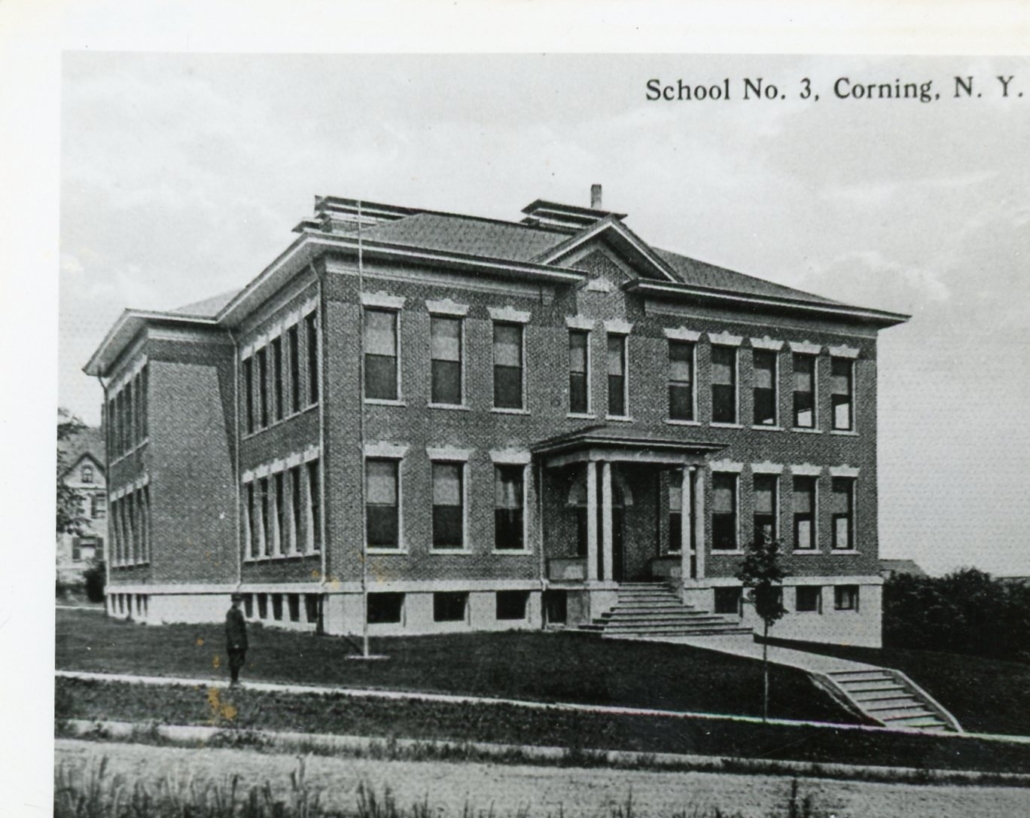

Susan was the eldest child in a prominent farming family. She attended this high school:

Susan was barely 18 when she married Alfred.

World events seemed to swirl around their lives as a young family. When Susan became pregnant with their second child, Norman, the Spanish flu epidemic was raging.

As soldiers returned home in 1918 they brought the flu with them and it tore through North American communities. Norman was born on November 8th and barely a month later Susan succumbed due to the flu.

Alfred had to carry on.

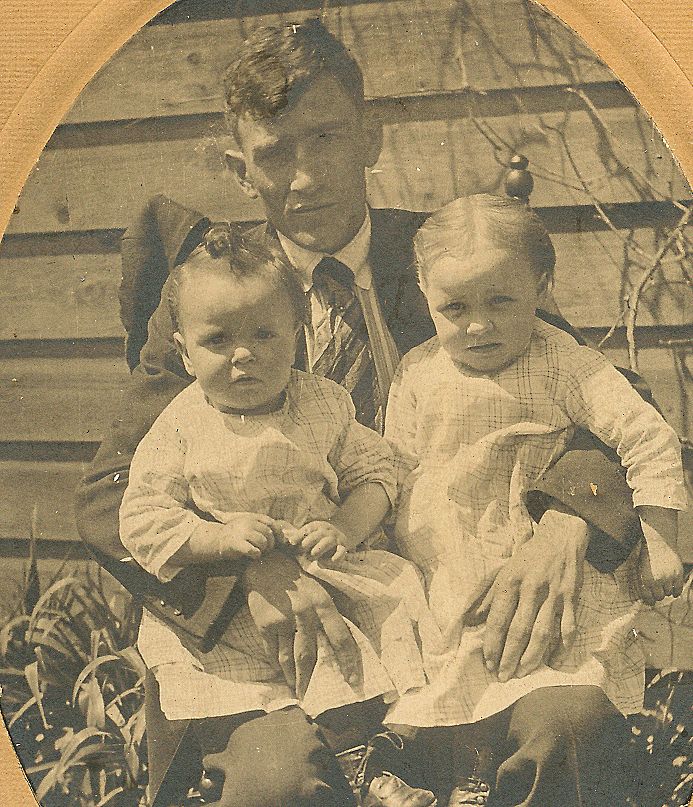

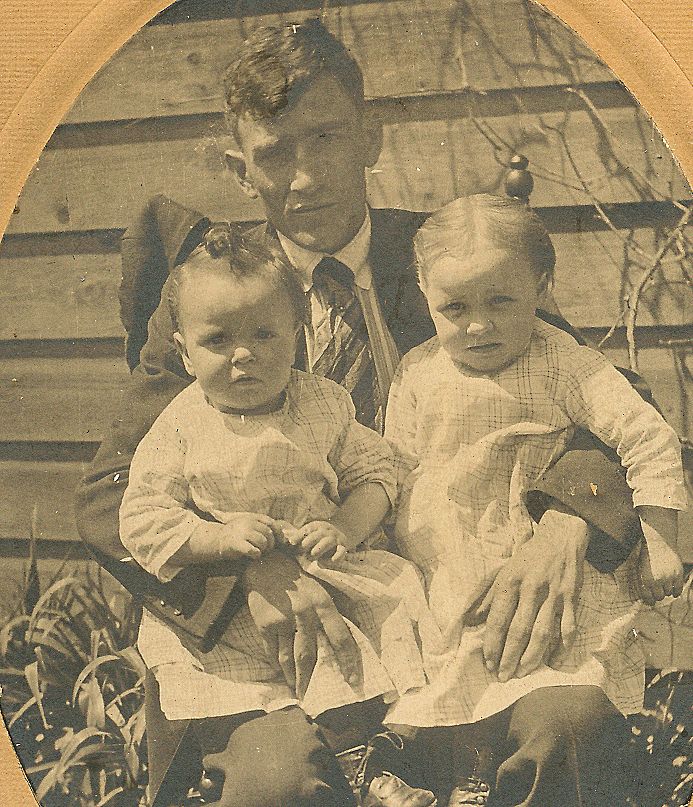

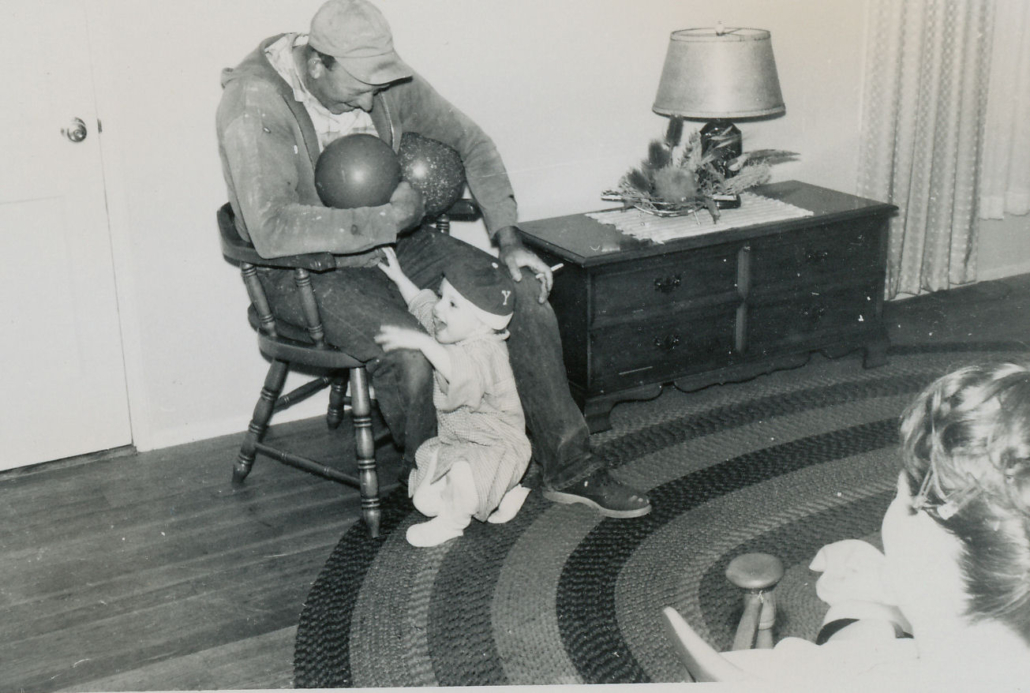

Census records indicate that he lived in the same house but took on a housekeeper with a young child to help with the children. Here is a surviving image from that time period of Alfred with Winnie and Norman:

Alfred survived for four more years when, near the anniversary of Susan’s death, he too passed away.

His obituary says he died of “four weeks illness of complication of diseases”. That cryptic phrase was used at the time to artfully say it was possibly an unnatural death. No official death certificate has been located. Alfred was just 29.

The family struggled to know what to do with the children. For a brief time, as indicated in state and federal census records, it is clear the children were passed around some between the Welty and Carson families.

Ultimately Norman was sent to live with “Aunt Emma”, who was Alfred’s oldest sister. She was 50 years old and married to a man named Benjamin Edwards at the time.

A state census from 1925 shows Norman still with Aunt Emma but she was no longer married. Benjamin shows up with another wife at a different address. Emma is 57 and Norman is 6, and they were living as boarders with a man named Blencow. Emma and Norman would later board at the home of Emma’s sister, Glenora, and her family. While living there Emma passed away in 1937.

For Winnie the story is a little different.

She was sent to the family of Willis H. Welty, Alfred’s oldest brother who was a farmer and the likely heir of the farm run by his brother George and their father, Jacob. Willis was married to Lydia and they had a family of several children. This is an image of that family likely taken several years before Winnie was born:

It was in the home of Willis and Lydia that Winnie would spend her childhood years.

Most census records list her as a niece. One record shows her as a maid, though it is unknown if that was a mistake. In later years Winnie would not have many positive things to say about her growing up years. Nothing has yet been found of her academic record, though she clearly attended school.

Of note in this image is the boy in the back, Lawrence Welty. Lawrence was one of the only members of the family that remained in contact with Winnie after she graduated from high school and set out on her own. He was noted by Winnie for his kindness. Many years later, in California, my parents would meet “Uncle Lawrence”, and they too recalled his kindness.

The only other member of the family Winnie kept contact with was her brother, Norman. Here they are shown together as children, likely on the farm of Willis Welty, and maybe around the time that Alfred died:

What do we know about the upbringing of young Winnie?

Not much. She was cared for, as you can see from these surviving images:

The full story of her childhood likely went with her. My mother was told by Winnie that she had an unhappy childhood due to abuse. What kind of abuse is not known. We do not know who her abuser was.

All we know is that she developed a keen distrust of family during her growing up years.

She left western New York as soon as she could after high school, taking nannying jobs with families who could provide her income and a roof over her head.

She never returned Corning.

And, other than Lawrence and Norman, she never had another contact with either the Welty or Carson families for the rest of her life.

~ Work, Marriage and Motherhood ~

In 1940 we find Winnie in Scarsdale, NY – hundreds of miles away from Corning, working as a maid in the home of a family named Allston. How long she worked for them is not known. What is known is that by the winter of 1943 she was working in New York City as a receptionist.

In the building where she worked she met a man named Carl Begich. He was an aspiring journalist. They began to court, fell in love and got married in May 1942. On January 11th, 1943 – Carl’s 24th birthday – my mother, Susanne Catherine Begich was born.

From the very beginning Winnie and Carl called her Cathi. The name had significance to both of them. Catherine was Winnie’s mother Susan’s middle name and also Carl’s mother’s given first name.

Thrilled as they were to begin a family, due to the war and world circumstances, it could not last. Just over a month after the birth Carl enlisted in the Army (that story can read in his history).

The Begich family hailed from Minnesota, a place where Winnie had never been. It is not known if she ever got a chance to visit there but she did at least get a chance to meet one member of the Begich family – Uncle Pete, Carl’s brother, who had come to New York around the time my mother was born.

The Army had plans for the talents of Carl Begich and it was thought for a time as he went through basic training he would be based on the East Coast for at least the first part of his service in the war. In his letters we read how Carl and Winnie discussed a possible move.

But those plans changed quickly when Carl received word he was to train in California. So certain was he of these new plans he asked Winnie to pack all she could with the baby and head to Northern California, where he would soon join her. So she went, at the height of the buildup to the war, and found a little place to stay in Port Chicago, California.

Carl never made it there.

Instead his orders were changed and he found himself sent to England, where he was put in a radio squadron. From 1943 to 1945, he wrote letters home detailing what he could of his experiences and writing of their future plans as a family. None of Winnie’s letters survived the war.

But reading from Carl’s letters we get a good idea of the stages of growth the baby experienced and all that Winnie was enduring as just one of many lonely military wives.

Carl wrote some cryptic letters in the winter of 1945. Clearly the war was coming to a close but his service, he indicated, would likely go on after the war was over. By this time he was working in military intelligence and his working future was completely up in the air. He told Winnie that if she received word that something happened to him she should not believe it.

In June of 1945, weeks after the war in Europe ended, she received word that he was missing in action. So did Carl’s family in Minnesota. Just weeks later, they were told that Carl had been killed in action (non-battle). Because of all the mysterious circumstances, and all the cryptic references from his letters to both Winnie and to his family, nobody could believe Carl was gone.

Carl’s father, Michael Begich, wrote letter after letter to the War Department seeking information of what had happened to him. It took years for a response and answers never really came to give his family closure. For Winnie the situation was even more complex.

What was she to do now? There she was, thousands of miles away from the home she grew up in, and she had nowhere to go and no one coming home to her.

There was an awkward exchange of letters between Winnie and the Begich family.

The Begich’s had suggested she consider bringing the baby and moving to Minnesota, where she would be surrounded by family. When she coldly rejected that suggestion the Begich family struggled to understand. More letters were sent, each rising in tension as rejection seemed to be the only reply.

My mother told me that Winnie later explained that she did not want Mom growing up as an “orphan among family members”. Winnie felt it best to carry on in life as a single mother than to expose young Cathi to family she didn’t know or, for whatever reason, couldn’t trust.

Trust was really at the heart of what Winnie was feeling and it came because of nothing any of the Begich family had done. It went all the way back to Corning and the family Winnie had known there.

~ Starting Over in California ~

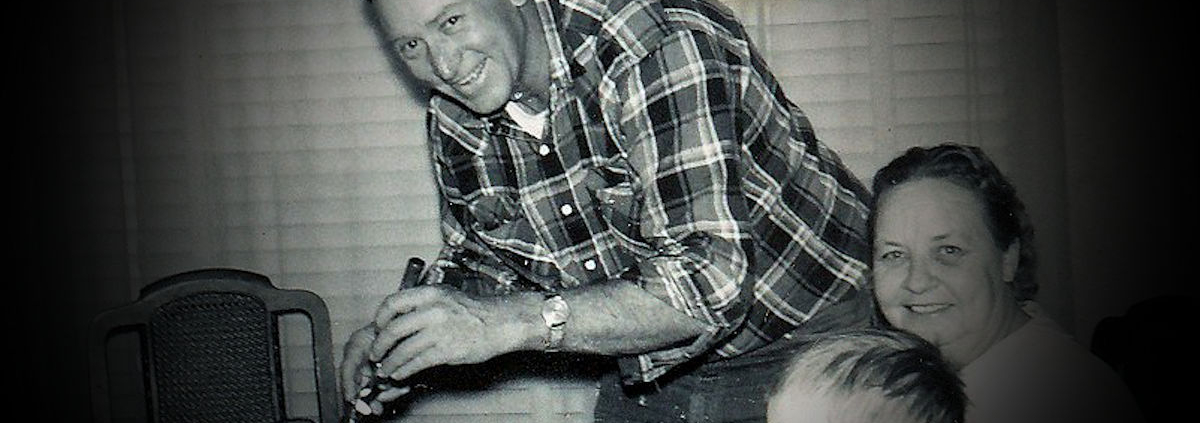

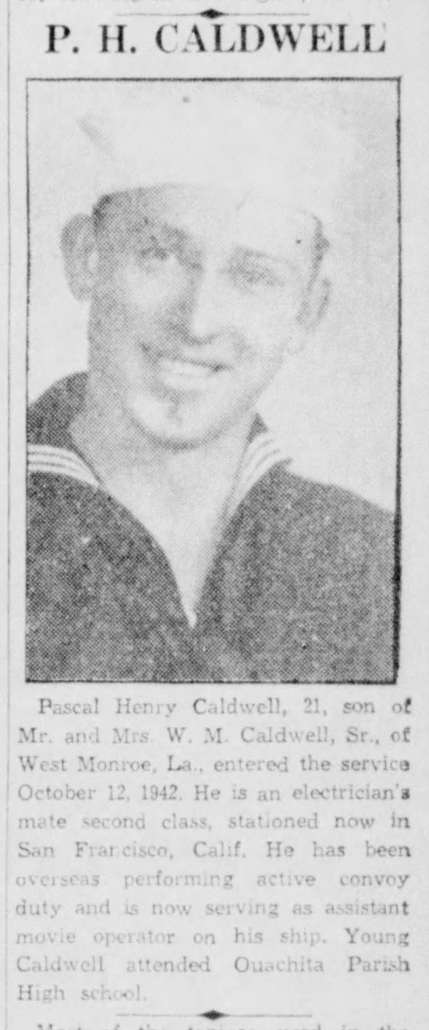

Cathi was Winnie’s family now. And life needed to be lived. As the men returned from the war in 1945 and 1946, Winnie met another, a man named Pascal Henry Caldwell.

As a person he could not have been more different than Carl. He was physical – a simple red-neck farmer with a huge smile, from Louisiana. Like her, Pat Caldwell had a difficult past with family and a future without them.

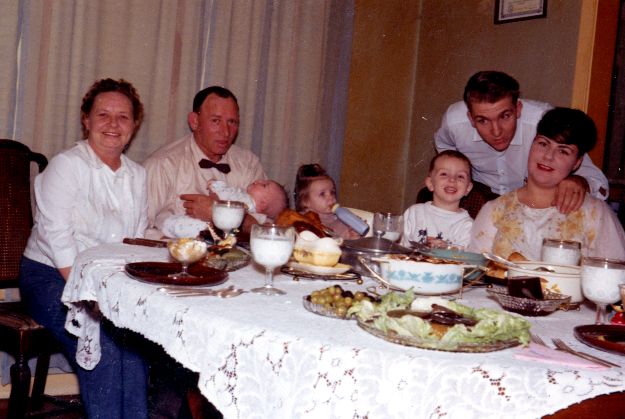

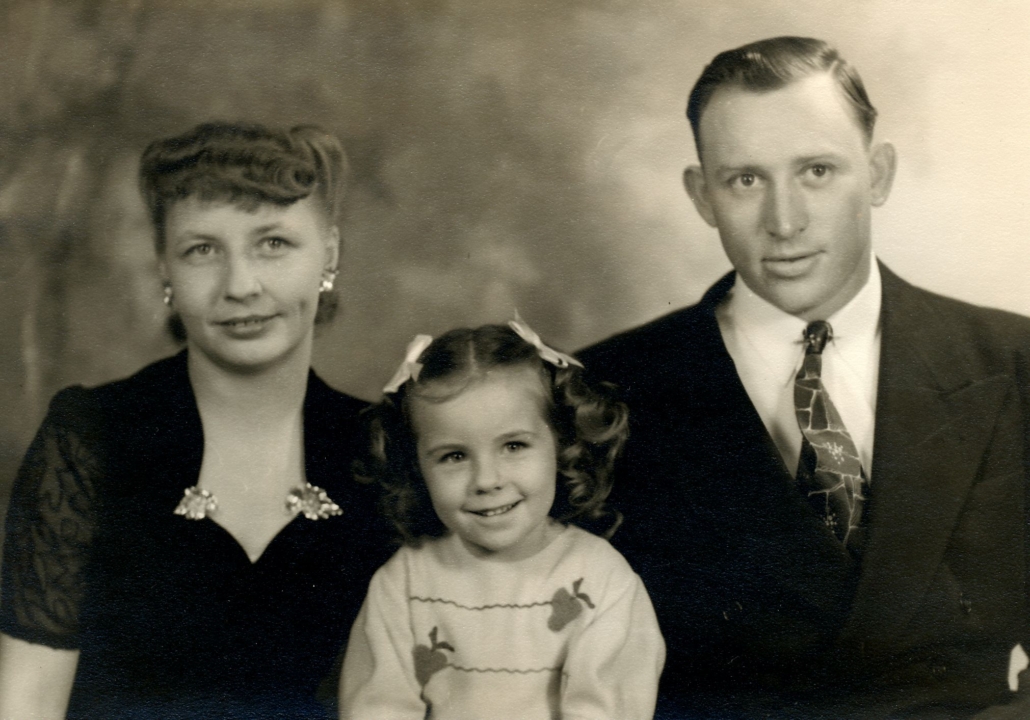

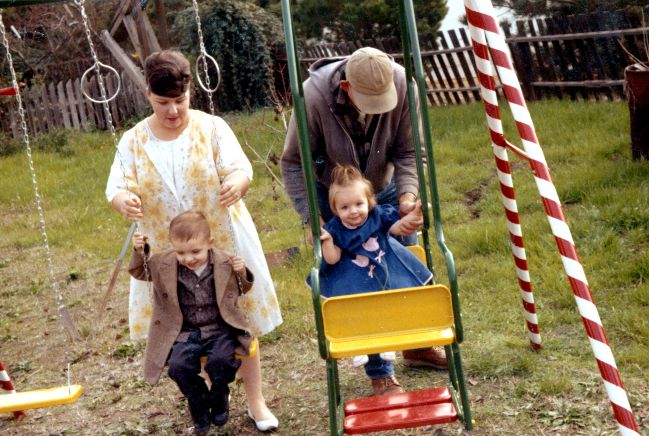

Where Winnie and Pat Caldwell connected was this: both had been severely traumatized by the war. They married in the Spring of 1946, taking this picture with young Cathi as they began their family life together:

Pat accepted an offer from the government for a civilian job as an electrician while they provided him with training and certification. California would be their home. They purchased a house on Detroit Avenue in Concord and would spend all of their years together there.

For all Cathi knew, Pat Caldwell was her father. Then she went to school, where she heard the Begich name for the first time. That impactful moment on the heart of a five-year-old created something of greater bond between mother and child. Winnie did not want Cathi to experience the pain she had in losing both her parents. She wanted to be honest as much as she could as the struggles Cathi might have with identity would surface.

Those things came to bear soon enough. Mom did not know this strange name, Begich. She didn’t want that name attached to her because her Daddy was named Pat Caldwell. Winnie quickly instructed the school to remove the Begich name from Mom’s records.

Sometimes other life lessons were tough for mother and child.

Mother tells me of the time when she was quite young, maybe 8 years old, when she decided to steal one of Winnie’s cigarettes. Her mother caught her in the act and sat her down right away.

Winnie lit up another cigarette and gave it to Mom to inhale. Then she held up a handkerchief and had Mom blow smoke through it. The white hankie turned yellow.

“You see why you can’t do this?” Winnie asked her. Mother later reflected that it seemed her mother was pushing her to become better than she was. “Mom always said I was better than her and could do more than she did.” Mom shared.

Mom also described how Winnie and Pat worked together to make life enjoyable for her growing up.

They supported all her efforts in school, took her on vacations, went camping, hunting and fishing. Mom told of the patience of her Dad when he hosted a barbeque for a pack of 10-year old girls who had come to celebrate Mom’s birthday. All this could be described as normal family life of the 1950s.

But beneath the veneer of normalcy resided a struggle with Winnie and Pat that made things difficult. Both had problems with alcohol.

Frequently mother would return home from school to find Winnie drunk, unable to function. Mom said she would have to straighten up the house, rush to fix dinner and make her mother presentable for when her father returned home.

Pat Caldwell worked at the Naval base. He started early in the morning, then on most days went to work part time as a county sheriff deputy in the late afternoon and evening hours. Once off duty from either job he would frequent a local establishment and drink with friends. It was not unusual for him to come home inebriated.

The combined forces of two drinking parents created many difficult situations for my mother.

It took her years to realize that both of her parents were suffering from aftereffects of their war trauma and family situations. Alcohol was their coping mechanism.

All she knew was that her mother was a very sad drunk and her father was a mean one. There were threats of violence, lots of family tension and frequent outbursts.

If dealing with their lack of sobriety on an individual basis was not bad enough dealing with moments when Winnie and Pat would drink together was worse. This usually happened during holidays and gatherings. Because of this my Mom grew up with a distaste for Christmas and birthdays.

During my mother’s teenage years she kept herself active in as many school endeavors as she could. While of course there were sober moments in the family’s daily life, and her parents remained supportive in her activities the alcoholism was ever-present.

My father entered the picture during the final two years of high school in my mother’s life. He would witness some of the trauma in the Caldwell home. For him, coming from a home without those issues, he found it difficult to connect with his future in-laws.

Pat Caldwell scared my father. He was a big man. He was a quiet man. He was a serious man. And when inebriated he was to be feared. Winnie Caldwell scared Dad too, but in a very different way. She did not trust him with her daughter and she told him that. He wanted to be trusted, and liked, but she questioned his intentions.

When my parents rushed to Carson City – the same place where Pat and Winnie went to when they married – they found that my mother was too young to get married without parental permission. Mom was still 17, having just graduated from high school months before.

So they both called home to Concord and sought out both sets of parents. Seeing that their minds were made up, both the Caldwells and the Westovers decided to come to Carson City to see my parents married.

They traveled together, having just met each other for the first time. In sharing this story with me Dad openly wondered what the conversation in that car was like for these two couples who had so little in common – other than their teenage children marrying each other. I share this part of the story of my parents here because it is insightful into the history of all the individuals involved.

Whatever happened in that car, and whatever ensued once the marriage happened in Carson City, it changed roles and relationships.

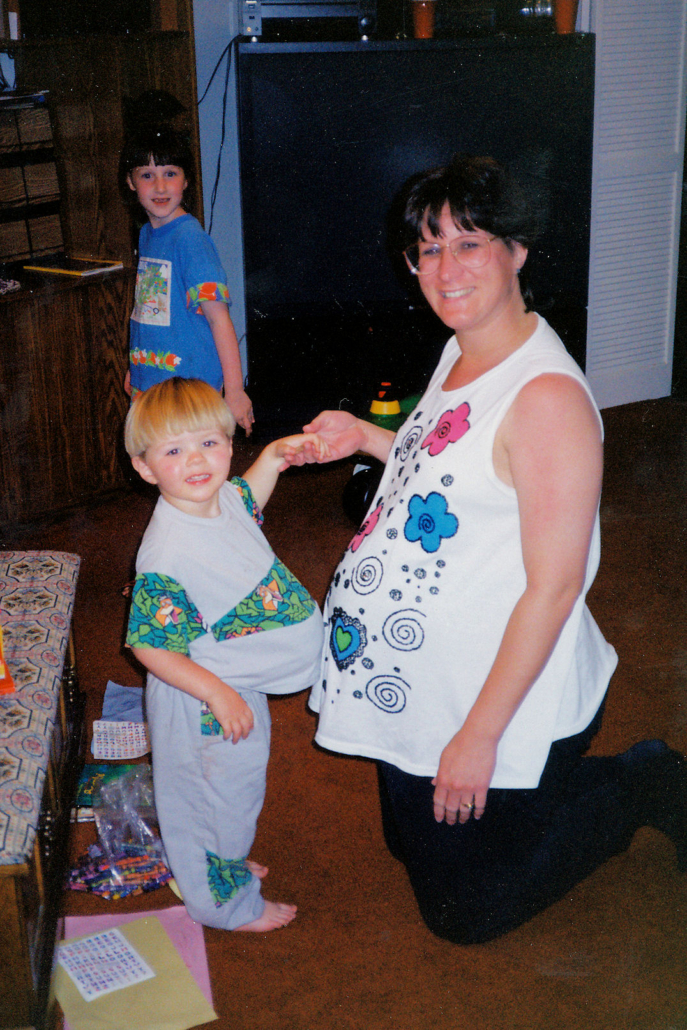

Months later, after my parents had moved to Provo, Utah, where my Dad was attending BYU, Winnie travelled to be there at the birth of their first child. My parents were living in a rented hotel room, having arrived too late to secure a house or an apartment at the start of the new school year. Winnie took an adjacent room while the days passed for the baby’s arrival.

After my brother was born my Dad was working as an usher at a theater. He was concerned because he was uncertain what Mom and his new mother-in-law knew about caring for a baby. He at least had some experience with siblings. But Mom was an only child and, to his knowledge, Mom was also the only baby Winnie had ever cared for.

Dad got home from work and wandered into Winnie’s hotel room where he found them in the bathroom, on their knees, bathing the baby and having the time of their life with the task. He quickly realized he was the real rookie in baby care as he watched mother and grandmother coo over my brother. The moment was one of many perspective-altering situations Dad would witness.

~ Later Years ~

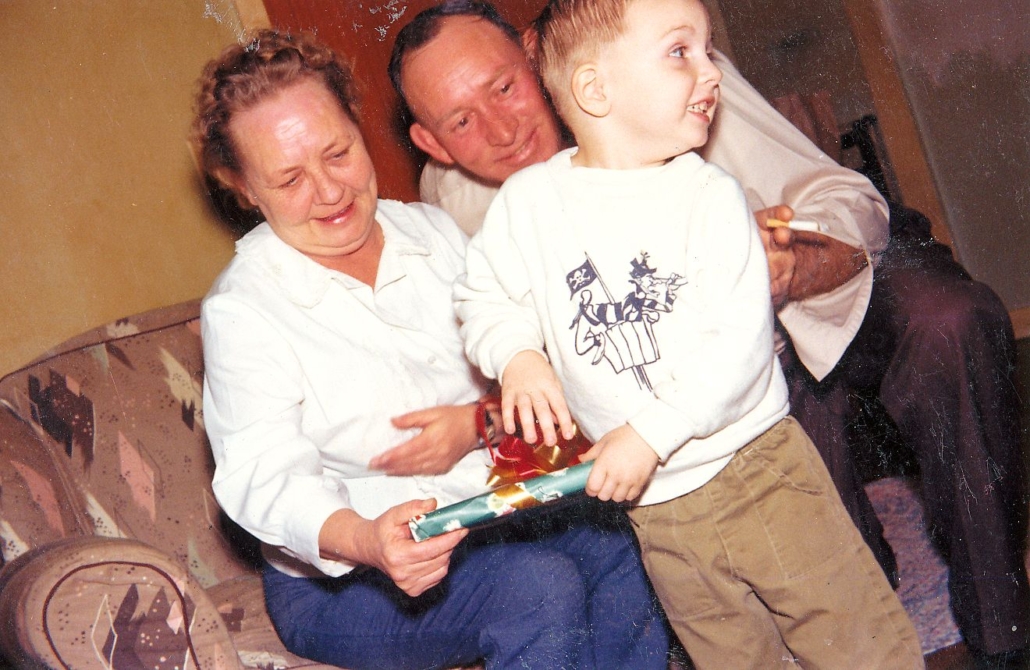

Grandparenting came natural to both Winnie and Pat. We, as grandchildren, called them Nana and Bumpa.

In the coming years of the early 1960s they relished their roles with the grandchildren. They became hands-on grandparents. They embraced each one of us, played down on the floor and in the dirt. Grandparenting gave them great joy.

For my father, these moments cleared the clouds brought on by alcoholism in his in-laws. He gained greater respect for them. For my mother, the impact was greater. She too saw something different in her parents, something she never got to see much or could remember as a child.

Mom told me of the time when my older sister was born and how having a girl seemed to affect Winnie. Nana really wanted Mom to have a girl. As Mother explained this to me, Nana was anxious to have granddaughters who could be strong and independent.

When my parents married there were many gifts given to help them set up house. One of the more significant of those gifts was a maple hope chest Nana had purchased with trading stamps.

Because of her problems with alcohol Pat would not give Winnie cash to run the house. He was afraid she would spend it all on alcohol. So she saved up green S&H trading stamps she collected when they would go out to buy groceries together. Years of saving these stamps allowed Nana to purchase the hope chest.

That chosen hope chest and what it represented to my Mom was the center piece of a new bedroom set my parents purchased after my sister was born. Because the hope chest was maple they wanted the rest of the bedroom to match. They purchased a maple canopy bed with matching nightstands.

When Nana saw this she cried. She felt the bedroom set was worthy of her daughter and granddaughter, who she felt needed to be treated as queens.

Dad told me in later years this was an event that changed things a bit between him and Nana. Earlier there were many things that happened that challenged him. One time came when Nana asked him to stop by the liquor store and bring her home a bottle of wine.

This was something Dad had to refuse to do. She was angry at that refusal and called him something of a prude.

He said he tried to defend himself by saying he was raised without alcohol and that being associated with it at all would affect how people would look at him.

Nana responded by saying that what other people might think was different than what other people actually do think. She admonished him to be worried about what all people thought not just people who were like him.

Dad said it was likely the first time he ever really felt mothered by his mother-in-law. It was a teachable moment because Nana didn’t hold back. Like the lesson of the cigarette when Mom was a child it was a moment where her own weakness was set aside for a higher idea. Dad described Nana as fearless when correcting him – and then fearless in showing greater love after the altercation was over.

Dad told of another time when Nana went on a summer vacation with them in 1963. The trip included stops in Disneyland in Southern California, Las Vegas, and later in Yellowstone.

Along the way they would stop in Gunnison, Utah to visit Uncle Gerald and Aunt Milda’s place to pick up a boat motor for a visit to Fish Lake.

Upon arriving in Gunnison Nana refused to get out of the car. She had no interest in meeting any family.

Anyone who knows Uncle Gerald knows there was nothing to fear. But Nana didn’t know Uncle Gerald, she only knew he was family and then not to be trusted. Dad had only heard whispers of these feelings from Nana and simply could not understand it. Dad and Mom went into the house and in a short time Uncle Gerald came out to the car.

Because it was hot, the car window was open. So he leaned in and chatted with her as only Uncle Gerald could. Mom told me that Nana was charmed and laughed and briefly conversed with him. But she still refused to get out of the car or get any closer.

Despite these kinds of things it is important to note how the Caldwells and the Westovers came together to support my parents.

That first semester at BYU proved to be too financially stressful for my parents. Dad said they returned to Concord, with himself feeling like quite a failure. As he discussed his options with my mother, and later with my grandfather, it was determined that my Dad should get a job right away and that a home somehow would be secured for our family.

Both sets of parents stepped up to help in significant ways. Both contributed cash for the down payment on the house on Crawford Street in Concord, situated between the grandparents’ homes on Detroit Avenue and Peach Place in Concord. My grandmother returned to teaching in case help with the house payments was needed.

Dad enrolled at Cal State Berkeley. It took him until 1968, holding down several jobs and getting help from both sets of parents the whole way in order for him to graduate. These combined family efforts – made for the good of our family – created a level of mutual respect between the Westovers and the Caldwells.

My Dad told me that how his parents handled the situation with Pat and Winnie Caldwell went far in helping him to adapt to his in-laws. He recalled the time when he converted the garage of the little house on Crawford street for an office where he could study. Both Dads had ideas, suggestions and a hand to lend in getting the project done. Both helped.

A question arose about flooring. Dad had one idea on how to do it. Grandpa had another and as they discussed it things turned into something of a debate. Bumpa walked in during the middle of the conversation and could quickly see where it was going. He gently sided with Grandpa and, Dad said, he encouraged him to apologize. He quickly did. However, Dad said the real lesson wasn’t in that he was wrong but in that the look on his father’s face was one he could never forget. Dad said Grandpa was shocked at what Bumpa had said and done. Grandpa, for whatever reason, didn’t think Pat Caldwell liked him much.

In later years, as I would spend time with my ill Grandma Westover in her final days, I asked her about my other grandparents. She told me what wonderful people she thought they were. She said that Nana and Bumpa had treated her and Grandpa like gold and she knew they loved us.

Mother, too, talked about how her parents and my Dad’s parents were thrown together and how different they were from each other. Mom said that when I was born both sets of grandparents appeared at the hospital at about the same time and how it seemed surprising to her when Bumpa reached out to shake Grandpa’s hand and say, “Congratulations”.

That little exchange surprised Mom because it was a moment they shared together as grandfathers. They had little else in common but they shared that and it gave her joy to see them so happy together.

My mom was there when Grandma Westover passed in 1987. It was a difficult situation for Mom. One of the first people she talked to after speaking with my father was Bumpa. He later told me it was one of the few times that my Mother had initiated a phone call with him. Mom told me that in that phone call that Bumpa was sad because he loved Grandma. He called her a great lady.

Such declarations were not easy for a man like Pat Caldwell to make.

~ Reflections of Others ~

My memories of Nana are very few. I was just four years when she passed away. In watching my wife now with our grandchildren I’m reminded of those memories I of have of Nana.

She was always so gentle and happy with me and, like my own small grandchildren now, there’s a magical connection with an engaged grandmother. That is why in later years, as I learned of her history, her personality and characteristics, I was stunned to learn some facts about her.

The first was her physical size. As a small child, looking up at her, she was as any other adult. She fawned at me from above. But she was only 4 foot 10 inches in height – a tiny woman. Of her surviving things a size six pair of heels give us a physical reminder of her petite frame. This was hard for me to imagine.

The second thing that is difficult for me to grasp about Nana is her demeanor. She has frequently been described to me as sad. In today’s terms you might say she suffered from depression. My memories are always of her vibrant smile and that deep dimple and sparkling countenance.

Mom would tell me that Nana would always say that I have “bedroom eyes”. To me, this gushing grandmother was nothing but smiles and love. My older siblings have the same recollection, though my older brother has much more detail he shares of conversations and experiences with her.

Nana, I think, was something of a tomboy growing up because she seemed very comfortable in a boy’s world of sports, adventure and getting dirty.

But I think most telling in history of Winnifred Calista Welty would be her feelings about womanhood.

Whatever her experience as a girl growing up she was intent on instilling in my Mother the necessity of strength, willingness to face things independently and to shake off the bad things that happen.

Mom felt her real connection with Nana expanded when she became a mother. It gave them something more in common as women. While “family” on a broad scale was something to be avoided in the eyes of Winnie Caldwell, “family” as it relates to children required fierce loyalty and devotion.

When Mom was pregnant with Jay, my older brother, Nana took her aside to lecture about how that child developing within her would forever be a part of her. “You share blood”, she would say. “You are forever connected”.

With each pregnancy Nana seemed to reinforce the bond between mother and child. In fact, with each passing pregnancy Mom said she found more love and connection with Nana. For Mom, having someone to share the tears and joys of nurturing children helped her understand Nana more.

That connection made Nana’s final difficult days very hard on my mom. They grew very tender as their relationship seemed to soar with each new grandchild and yet suffered with the ongoing issues with alcoholism.

Nana never got a handle on it.

In the spring of 1967 at the age of 49 she went into the hospital with liver failure. She passed on March 7th. My mother was 24 years old and Nana’s passing devastated her. For years afterwards my Mom would tearfully account for the many ways her mother was her best friend and confidant.

Other members of the family have lent their insights about Winnifred Calista Welty to me.

In the early 1980s, as I was assisting Bumpa in clearing out his properties as he was leaving California to return home to Louisiana, he declared his love for Nana in a very rare moment of spoken expression.

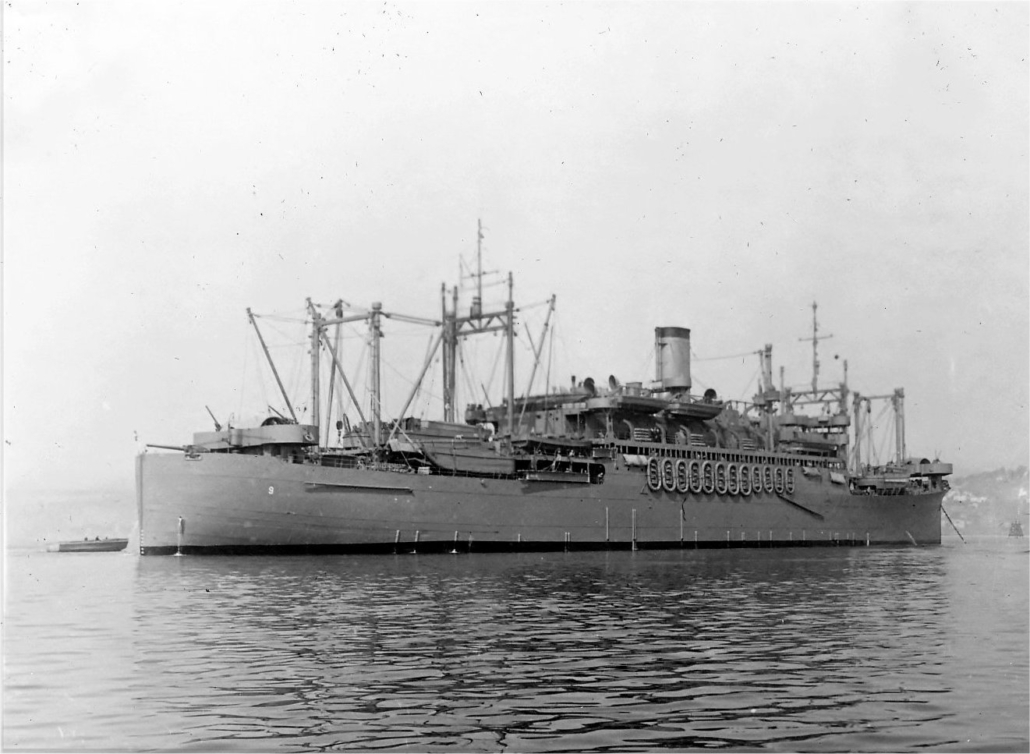

I was actually trying to get details from him about his war experience. He experienced many difficult things during his time all over the Pacific in the Navy during the war but he would never tell me exactly what happened. But in discussing his decisions in coming home, meeting Nana and settling in California he said “she understood everything” and that he really, really loved her.

Knowing him as I did that was an amazing statement.

In my mother’s later years, when health challenges frequently put her in the hospital, Mom would often bring up memories of her mother, even though Nana had been gone for more than four decades. During a hospital stay in 2012, when Mom suffered from something they call hospital delirium, I witnessed Mom hallucinate a scene where she saw Nana.

It bothered me to witness this and I later asked the doctor about it. The doctor explained that while the circumstances one might think they experience with this condition are usually nonsensical the people they see in these visions are typically people of great importance. The doctor asked me to describe what Mom said she saw and I told her about Nana. She was dumbfounded to learn that Nana had been gone for so long. “She must have been a very central figure in the life of your Mother,” the doctor told me.

Even my Mother’s final days, when more lucid experiences that come when the veil is so thin, she described seeing her mother reach out to her with open arms. When this experience happened my sister emphatically advised Mom to “Go to her, Mom – it’s okay”.

Mom’s arms were outstretched, a smile was on her face. But she leaned back, put her arms down, and simply said, “Not yet”. Hours later I asked Mom about it. Yes, she told me, it was real and “Nana looked so good”. Then mom shared something I never knew. “She has been here the entire time. She already knows everything about us. Nana only left her body behind.”

This explained during so many of my growing up years why Mom usually spoke of Nana in the present tense.

When I was 8, my little sister was born. She came several years after Nana had passed. I recall my Mom talked about my little sister’s dimple, a feature she shares with Nana. Mom said that dimple came from when Nana kissed her in my sister’s pre-existence. It was a simple, serious declaration – not a wistful wish or a sentimental memory to my Mother.

I can recall rainy spring days every year when my Mom would get very quiet.

I would ask her what was wrong and she’d say, “This reminds me of the day my Mom died”. That was about as down as my Mom seemed to get when speaking of her mother. Often, Mom talked about her in brighter terms and in a more present way.

As a teenager I experienced an event that made me very sad. When something bad happened to me, Mom would always remind me that “Nana would not like to see you sad” or “Nana doesn’t think bedroom eyes should cry”.

My mother’s journey in exploring the family history of her parents began in the early 1970s. After I served a mission and returned in 1984, I accompanied my Grandma Westover to the new family history library in Salt Lake City. She showed me how to look up names and how to operate a microfilm viewer. Grandma also very wisely admonished me to work on my mother’s family lines because Grandma knew they needed a lot of work.

So I called my Mom to ask where to start and she gave me some information she had about the Welty line. I came out of that week in the library with several paper copies of records Mom did not have, a fact that enthused her.

Based on that experience I made the decision to make a trip to Minnesota in an attempt to meet my great Grandma Begich, Carl’s mother. My cousin Bunni and her father, Uncle Pete, were very supportive.

My Mom, however, was reticent.

While she feared rejection of me her greater concern was a lingering anger against Nana. Mom was not sure if all the bad feelings over what happened so many years before had subsided.

I did not get to meet Great Grandma Begich, it was simply too much for her to handle. I was not there to hurt her and I told Bunni and Pete how much I appreciated their many efforts to make it happen. But I heard nothing but kindness from all the Begich family when it came to feelings about Nana and my mother. They did not understand and expressed that but at the same time they also, after all those many years, expressed great compassion for both Mom and Nana.

The many kindnesses shown to me on that trip, and the photos and memories I was able to collect of Grandpa Carl, did a lot of good in building love with those of us who came after it all happened. What I learned of Grandma Begich sure seems to fit with what I know of my mother and of Nana. Now that they are all on the other side, I wonder what that first meeting between them looked like.

The commonality of children, grandchildren and now great grandchildren between them all has to be something of great joy to them all. Grandma Begich’s history, which still needs to be written, shares much with both Nana and Mom. She too was a woman who had to overcome great loss to raise a strong family of great love and tradition.

I know for Nana that reality, and the memory of it, was something of greatest concern to her. Mother, and by extension, the rest of us, was the focal point of Nana’s life – her greatest accomplishment. Despite the great trials and her own weaknesses it was her life’s work. She took it seriously and did her very best.

When Bumpa told me, back in 1982ish, that he loved Nana he used a phrase I didn’t account for much significance at the time. But I wrote it down, thinking to ask my Mom about it later. He said, “She was feisty with me about your Mom. That was one way she told me she loved me.”

When I asked Mom about that – and it was before Bumpa died – she cried.

Mom shared that in later years, after Nana had passed and Bumpa had gone to AA meetings to overcome his battle with alcoholism, he was moved to seek her forgiveness.

That too had to be a hard expression for a man like Pat Caldwell to make.

Mom and Bumpa became very tender with each other as the years took their toll on him. I asked Mom if Bumpa ever told her about his love for Nana. She said he never used the words, not with her. But Mom was clear to me that he showed it to her, over and over again. She had no doubt of it.

Nana and Bumpa were good people.

I know my Mother would want anyone reading this to know that. She charged me with conveying that in our family history efforts. But I think their ultimate actions, and many great sacrifices, say it better than anything I can share here.

When Bumpa died Dad said that “he lived his life in crescendo”. I think that can be said of all those associated with the Winnifred Calista Welty story.

Nana did not give up entirely on her New York family. Two individuals remained in contact with her.

Her brother, Norman, served in WWII. Grandpa Carl’s letters mention attempts for the two of them to meet up somewhere there in Europe, though they never could find a way to find each other to make it happen. There were letters. Clearly Carl and Norman were acquainted with each other.

When Uncle Norm came home from the war he too married and raised a family. Letters and phone calls between Winnie and Norm occasionally happened. When my Mother married and started our family every Christmas featured a Christmas card and a Christmas package from “Aunt Eris and Uncle Norm”.

Those simple efforts were a vital connection for Mom and, by extension, for us. In later years when work travel took them to New York, Mom and Dad were able to make a visit there in Montour Falls. They were folks who were so often welcoming and loving.

I mentioned Uncle Lawrence above. He was the older brother figure in Nana’s childhood, as the eldest son of Willis and Lydia Welty.

As I understand it, his own life journey took him to California as well during the war and he visited with Nana and Mom several times. In later years, when we were little, he became acquainted with Dad and for us he built a wooden rocking horse which my Mother painted. It remained a fixture in our home for many years.

Tragically Uncle Lawrence died on the day of his mother’s funeral, in a terrible car accident. So we never got a chance to know him. But he made an impression and he was spoken of with great kindness by Nana.

Mom says that Nana rarely spoke of her childhood or where she came from. Ironically, much like Grandma Begich had to do with her feelings about Grandpa Carl, Nana had to push those memories out of her mind and leave them far behind.

One of the elements these great women – my Mother, my Nana and my Grandma Begich – share in common is unbearably hard things they had to face as mere children. Each lost a parent while very young.

Words were not there for them to express how much that affected them. It was not unkindness on their part in going silent in later years over such pain. It was their love, for past in their parents and for future in their children and grandchildren, that helped them overcome.

If I could have an adult conversation now with Nana, and maybe someday I will, I would tell her that despite it all she did overcome. She was successful in her best efforts. She got past all that she had experienced and she did very, very well.