Food and Stuff of our Forefathers

When my Dad passed I inherited his vehicle. By the time that came I was well familiar with it because I had driven him all over in it.

But one day recently, now more than 2 years since Dad left, I found a button on the dash that popped out a cup holder, something I previously didn’t even know was there. It held a little tray with just enough space to hold a small amount of change.

I looked at it and marveled a bit. “Dad put that there. That is Dad’s money” I thought.

And I haven’t touched it.

It’s just quarters and dimes and pennies. Probably less than a dollar’s worth of everyday cash. Nothing special about it.

But I can’t touch it. It’s Dad’s money – there’s just something comforting about seeing it there and having it in what I still consider to be Dad’s car.

What makes “stuff” from our loved ones so…special?

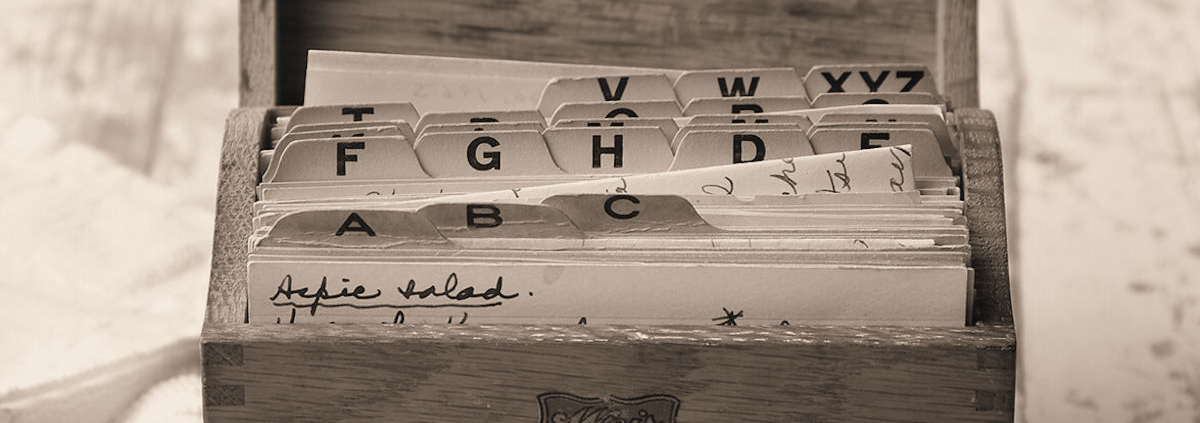

~ Grandma’s Recipe Box ~

My wife somehow inherited two similar looking file card boxes – recipe boxes is how my generation would look at them. My grandmothers had them too.

Inside, on 3×5 inch index cards, are handwritten recipes, some so tattered from year after year use they have notes written in both pencil and pen.

To pull cards from these boxes now is like stepping back in time for my wife. She can see, hear, feel, taste and smell the memories from these treasured recipes.

I’ve studied these little boxes and have decided they are the most valuable bits of family history information. It’s the stuff that goes beyond headstones and family group sheets.

They are snapshots into the personalities and passions of two cherished women in my wife’s family.

We’ll scan those cards and preserve them, just as we would any birth or marriage certificate.

From these recipes we can make Grandma’s fudge at Christmas. Or her funeral potatoes for, well, funerals.

There are many ways for Grandma’s to live on.

~ Pumpkin Pie ~

Perhaps one of my favorite connections to family past comes from food.

You don’t need physical artifacts if you just know how they ate. After all, if we eat the same, we have a connection, right? Let me give you an example:

Several years ago I was chagrined to learn that National Pumpkin Pie Day falls on December 25th. I found that to be a curious fact and I began to research why.

I knew that pumpkin pie was a New England thing. I understood that many of the earliest settlers in New England, such as our Westover grandfathers, were Puritans.

A lot of our modern-day traditions of Thanksgiving and Christmas were born of our Puritan ancestors.

The Puritan pilgrims of Massachusetts and Connecticut were supposedly famous for shunning Christmas. Historians have long said they didn’t celebrate Christmas at all.

They did this in protest of the Church of England, who had corrupted the celebration of the birth of Christ with pagan practices made famous during their day.

But in researching their love and use of pumpkin as part of the holiday season I found that our Puritans DID celebrate Christmas.

And I began to understand why pumpkin was such a huge element of that season of celebration.

Thanksgiving as we celebrate it today had its genesis in New England.

A “Day of Thanksgiving” could be called at any time where good fortune or the blessings of Providence were accounted for in community events.

It might have been a battle won in war or a good season of raising crops – at any time it was the tradition of British rule to occasionally call for a day of thanksgiving.

For our Puritan ancestors this usually came during harvest season.

For more than 200 years before Thanksgiving became a “national holiday” it was a custom to go “over the river and through the wood” to gather as families to celebrate Thanksgiving and to begin a holiday season of celebration that included the sacred Christmas.

Thanksgiving was usually just the start of a “holiday season” for Puritans, a time where they would gather as family for the first time all year.

Journals and newspaper accounts, such as they were, document this reality.

And they documented it then much as we do now: with invitations, with recipes, and with traditions repeated year after year – and with statistics.

Pies were a common element of these seasonal family gatherings: apple, pecan (or walnut) and especially pumpkin.

Why?

Because pumpkin was the most plentiful and, frankly, the cheapest.

Did they like it? No, they LOVED it.

In 1630, a writer wrote:

For pottage and puddings and custards and pies,

Our pumpkins and parsnips are common supplies:

We have pumpkins at morning and pumpkins at noon,

If it were not for pumpkins, we would be undoon.”

In the 1720s, the love of pumpkin was going strong:

Ah! On Thanksgiving Day, when from East and from West,

From the North and from South come the pilgrim and guest,

When the grey-haired New Englander sees round his board,

The old broken link of affection restored.

When the care-wearied man seeks his mother once more,

And the worn matron smiles where the girl smiled before,

What moistens the lip and what brightens the eye?

What calls back the past, like the rich Pumpkin Pie?

By the early 19th century pumpkin pie was so prolific that the media of the day estimated that it took 10 pies per family to satisfy their holiday cravings.

From the mid-17th century, in Windsor, Connecticut – home of Jonas and Hannah Westover – comes this common recipe for pumpkin pie:

“Pare and cut the fruit into small pieces, stew till it is soft, strain it through a coarse sieve or cullender, add milk till it is of the consistence of a thick custard; to each quart of this add three eggs, sweeten to your taste, and spice it with nutmeg and ginger. A little wheaten flour can be shaken in to thicken it. It is then to be prepared on a bottom paste, and backed like a custard pie.”

My dear wife, who is a pumpkin purist, declares this pretty close to the “right way to do pumpkin pie”.

And that’s good enough for me. I can no longer celebrate Thanksgiving and Christmas without thinking of the Westovers of Connecticut and Massachusetts of 400 years ago. Or without pumpkin pie.

~ How to Preserve the Stuff ~

The old movies, pictures and journals and videos from folks now gone are important. You know I love them and you know I’ll be wrangling with the quarter of a million images I’ve gathered from all sides of our families over the years.

But I’ve really been wrestling with “the stuff”.

I’ve told you about our treasure room – and the now extra storage unit of “stuff” I have taken from my Dad’s former home.

What stays and what goes?

I know I’m not alone in grappling with that.

My mother was well known for her love of the grand babies and her talent for crocheting baby blankets. Mom just worked on them non-stop and stockpiled a ton for future grandchildren and great grandchildren yet unborn. I inherited the extras.

Every time a new baby comes along – and we’ve added 10 of our own in the past nine years – they get a new blanket from Nana.

That’s an exciting bit of stuff to still have from my mother.

But other things hold value as well. For example, my Mom over the course of her adult life collected chickens.

No, not live chickens. Ceramic, clay, wood, artistically rendered chickens. One sits above my fridge in the kitchen and it gets noticed a lot. It’s a little piece of my Mom in our home.

I don’t know what happened to all of Mom’s chickens and I don’t care at this point. I have one and that’s enough.

Same goes for my Dad’s bust of Mozart. How that thing escaped damage in all the moves is beyond me. But it dates back to before I was born.

I see it now – next to Mom’s chicken – and it reminds me of Dad.

This is all family history.

I struggle right now to understand what will become of the stuff I’ve gathered that I consider family history.

I am trying to explain it all to my children in hopes that someday it will become their cherished stuff, too.

Thank you!