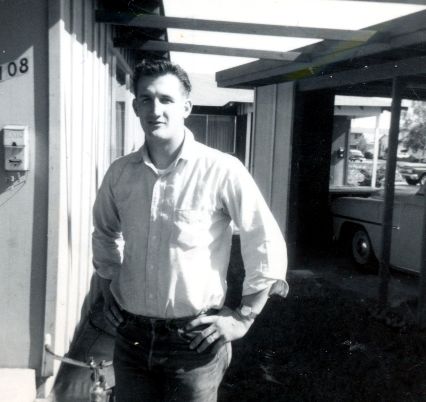

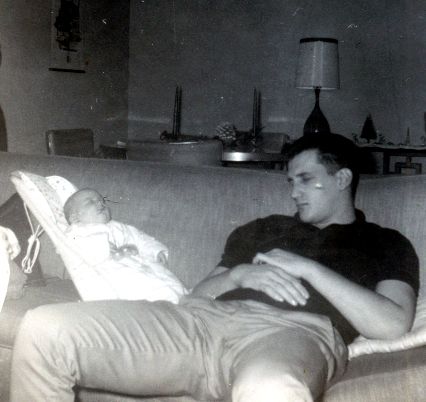

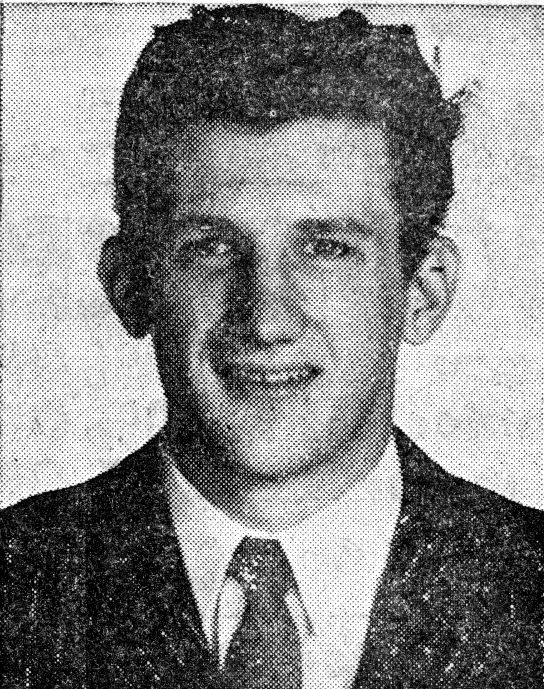

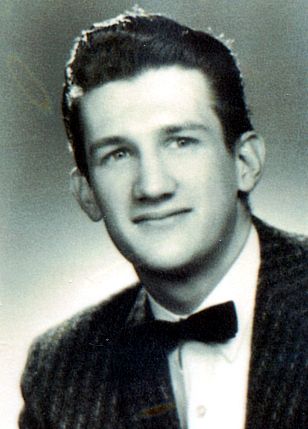

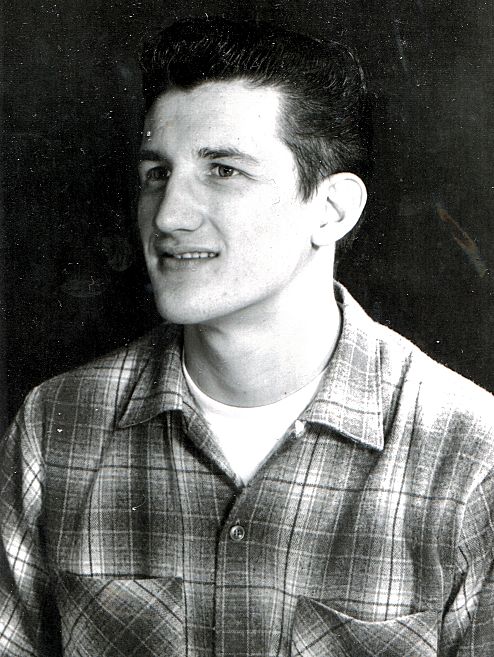

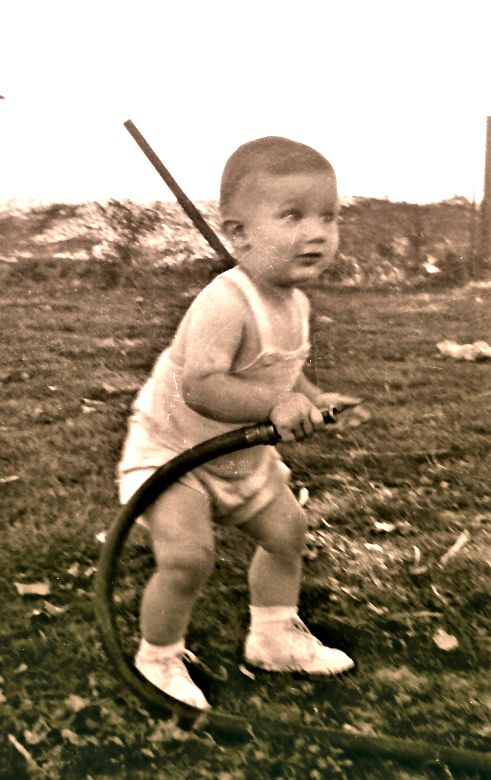

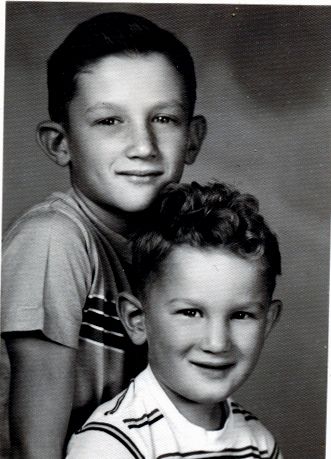

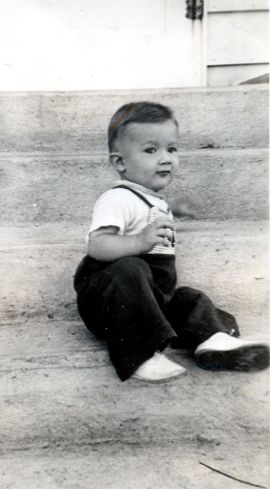

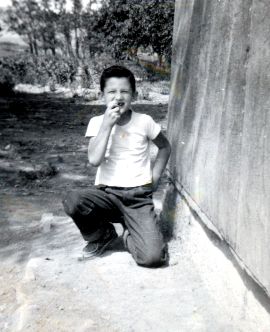

Today is my father’s 81st birthday. Well, it would have been. Dad passed in November 2021.

I have not yet published the history he was working on because it is not complete. I am finding that it is difficult to finish what he began.

So many times I heard Dad say, “We need to make a record!”

But the record of his life story is one I feel I just need time – and likely a lot of help – completing.

But I will take the occasion of this 2nd missed birthday since his passing to put down on record some thoughts that are important to me.

Grief is a process — one I have thoroughly experienced since Dad passed. It is normal. It is, in my view at least, just another level of love that is hard to put words to. I experienced this with my Mother, too.

For months after her expected passing I was weepy at times and caught by surprise at other times when her memory came up. For whatever reason I have found it difficult to visit her grave.

For a guy who loves cemeteries and celebrating family I just haven’t found much to be fond of in visiting where Mom is laid to rest.

I must confess that I haven’t been back there since Dad’s funeral either.

But part of the grieving process is letting go of certain things and I hope to do that as I “make a record” of my time with my Dad at the end of his life.

I’ve detailed some of the circumstances of ending up there at Dad’s house in this post. I won’t cover that ground again.

I’ll just say it was never a plan any of us had where I would be a caretaker for Dad.

I don’t know, really, what his plan was, frankly. I don’t think any of us give much thought to being old and dying. Dad certainly never felt that was where he was at on his journey.

But in the fall of 2020 we had a brief conversation about moving forward.

I basically said, “Dad, either I live with you or you come to live with me. But you just cannot be alone any longer.”

To my great surprise, Dad agreed.

I can recall discussing the time Dad had with my grandfather in his final year. He told me about having to talk to Grandpa about giving up his car keys.

Grandpa just wasn’t hearing it. He fought against the idea that he might be a danger, that he could not see well enough to drive and that the car had sustained significant damage due to hopping curbs and cutting corners.

Dad told me he didn’t want to be that way when one of his children had to have “the talk”.

But I know Dad never really thought about the time when it would happen to him. For a planner, this was just not something he had planned for. And neither did I.

But I kind of marvel about how it all came together.

It happened during the pandemic. It happened at a time when my wife was experiencing a similar situation with her parents. It happened at a time when I had adult children living in our home who could take care of house so I could be away. It happened right after I started a new job and they were open to the idea of working remotely due to Covid.

We decided to stay together in Dad’s apartment because Dad’s doctors were so close by and every doctor appointment would mean a 100-mile drive if he came to my already full house in Cache Valley.

It was a kind of obvious decision. So I moved in and just like that our lives became embedded in each other.

We had already been through the Covid thing with Dad. Though vaccinated his journey with Covid was complicated by his cancer.

In late September 2020 he was trying to get in to see his doctor and they required a Covid test. He took it and on the day I arrived he was informed he tested positive.

He had zero symptoms and felt fine. However, because he was a cancer patient, they wanted to see his lungs and sent us to the hospital for X-rays. I took him there and hours later we were dumb struck to hear a doctor there explain that Dad had double pneumonia.

While Dad had no symptoms at that time the doctor predicted that within days he would be suffering and, boy, was he right.

The doctor had ordered an oxygen tank and told me to put Dad on it at night. I did that but by the time that weekend rolled around he was on it 24/7 and Dad was as sick as could be.

This is really where my caregiving journey began.

I’m not the caregiver type. My sisters largely took care of my Mother and I assisted at times only when Dad would call to have me come help move her when she could not help move herself. Considering all the intimate care my Mom required I never considered myself an active participant in that mostly because that just wasn’t work I could do.

But here I was with Dad and the first real crisis I faced was getting through Covid. As many others experienced, Covid was many and different things to different people. In Dad’s case, it was difficult for me to understand all the dynamics presented with his cancer and how Covid acted with it.

He ended up in the hospital with Covid for a few days and I can recall those many hours being deep in research trying to understand the cancer my Dad had.

He passed out twice during his run with Covid. Was that Covid or cancer? What caused it? How could I ensure he wasn’t standing when these episodes would hit when he passed out? Would Dad go through covid and cancer only to lose his life to banging his head due to a fall?

The first time it happened he was in the bathroom. He had washed his hands and was making his way back to bed with his walker and he kind of leaned to one side.

He said, “Jeff, you better get over here-“ and down he went. I got there only to save his head and shoulders from hitting the floor. That experience began a routine of me talking to him every time he would black out. Sometimes he was out cold and could not respond. He’d be breathing and I’d feel he was safe, but I’d have to wait a minute for him to come to.

Other times he would not be able to see or move but was still with it enough to respond. He would always say the same thing, “I’m here – hold on.”

Now, one thing Dad and I discussed at other times about his history is that he didn’t want his cancer to define him. I am pleased, after all these months since he passed, my memories and feelings for Dad really have little to do with the disease that ultimately took him. But I feel there are valuable lessons to be had from the last 18 months of his life and the cancer was pretty much the center of everything. It limited him and it freed him, all at the same time.

Whether God intended him to change as a result of cancer is something we’ll never know. But I do know that Dad experienced worlds of change during that time and I think it is important to note them in his history.

When he had Covid I felt a need to give Dad a blessing. But, not wanting to expose anyone else to Covid, I called my Bishop for advice. He told me he felt I could give Dad the blessing alone.

Within minutes of that conversation there was a knock at the door and there stood the Harrisons, my Dad’s ministering couple – all masked up and holding yet another goodie plate. Dad had called them telling them not to come over due to covid. So, of course, they came.

Brother Harrison is retired military, a full bird colonel. He’s about as solid as they come and I told him immediately about wanting to give Dad a blessing without passing along Covid.

Brother Harrison said he understood but, as luck would have it, they had recovered from Covid and he would gladly assist.

So right then and there we gave Dad a blessing.

My experience in giving blessings with pretty extensive, but most of the time I gave those blessings with Dad and for other people – many times for my Mom. I was nervous but felt compelled to bless Dad that he would recover from Covid and he would have time to do the things he wanted to do.

I can recall afterwards thinking, “What did I just say?” but Brother Harrison put his hand on my shoulder and said, “That was the right thing, Jeff. You got it exactly right.”

And Dad did recover from Covid.

I had no expectations going into living with my father because I never expected to do it.

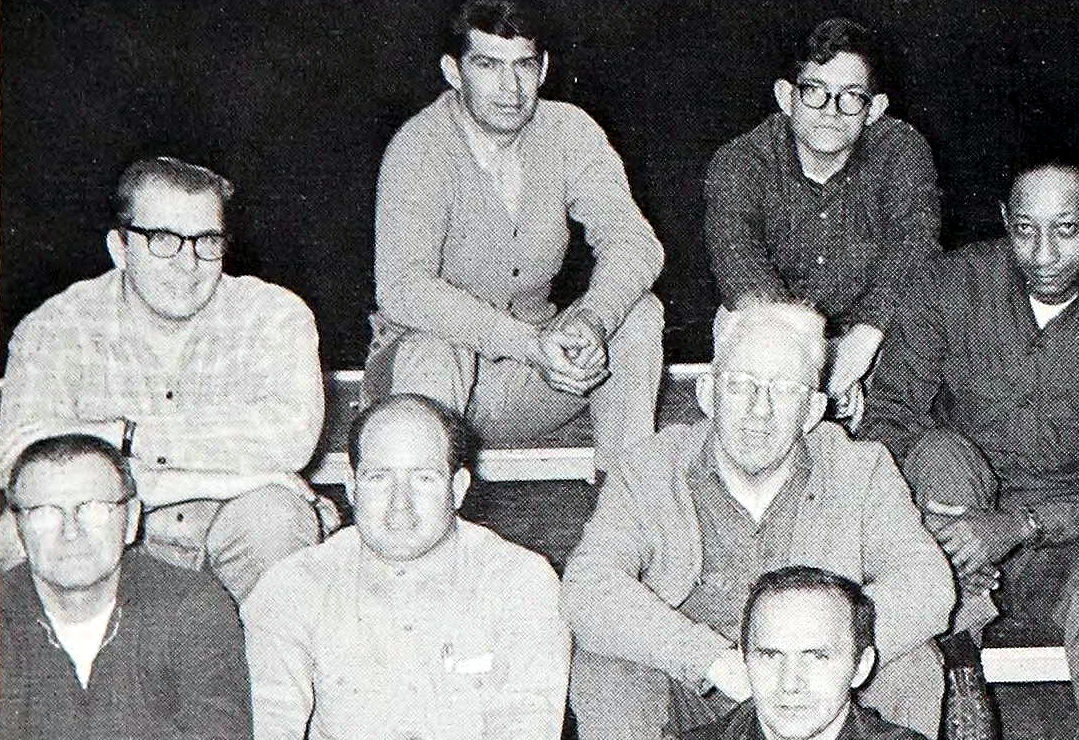

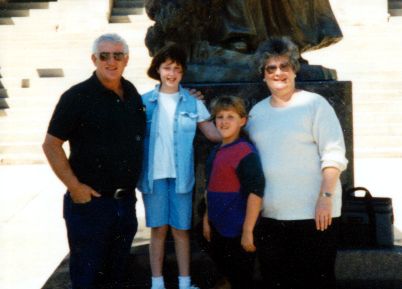

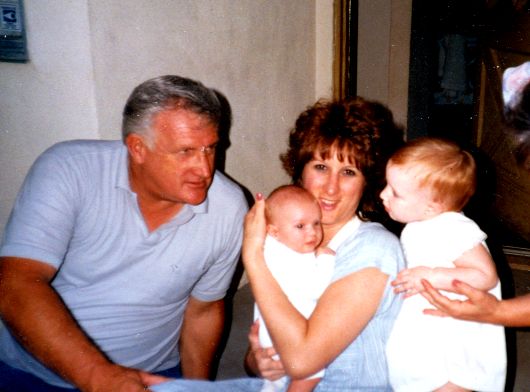

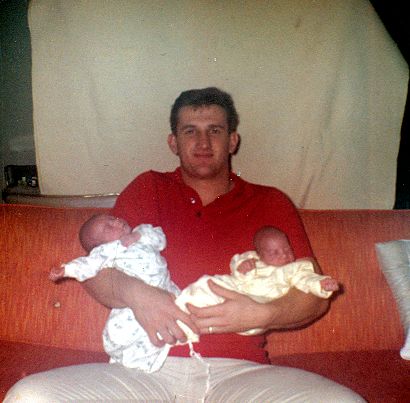

Several things took me by surprise, the greatest of those being that my relationship with my Dad went to a whole new level. Part of that I think is because we had reached a plateau of sorts in our roles. We were, at this stage of time, similar in that we were both sons, husbands, fathers and grandfathers. We likely had more in common that we ever had before.

That led us to talk frankly, candidly and more importantly, constantly.

Dad’s cancer and how we dealt with it all was kind of a common denominator for all our conversations. He knew he was dying. I knew it. We didn’t shy away from it.

We also didn’t dwell on it. Things were always very positive and forward-looking with Dad. Always.

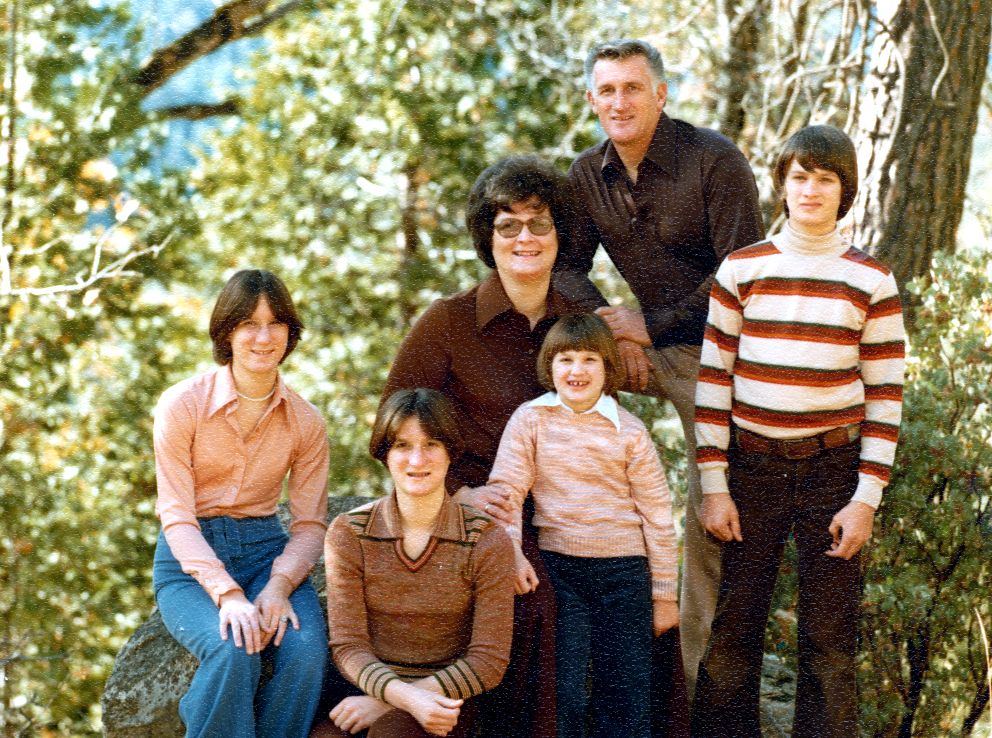

Six months after my mother died, my sister and I listened to a surgeon after nearly 9 hours of exploratory surgery try to explain my Dad’s cancer. That is when I realized Dad was dying. The doctor gave him five years. That was in 2015. Here I was with Dad in late 2020. His time was short.

Though we didn’t really bring it up the cancer and his mortality became a kind foundation for a lot of our conversations.

In the previously mentioned post, which talks a little about Dad’s broader discovery with family history, we often wandered into discussion of the post-life experience and who Dad would meet there. We had discussed it in the past in regards to my mother, who must have had reunions we can only imagine.

These were hopeful things for Dad, not only to be in presence of his parents and other loved ones again, but to meet some of the heroes of our heritage that passed before he was born.

One such individual is Albert Smith, his paternal grandmother’s grandfather. Albert’s life story is presented in this post.

Dad and I had worked for a few years on a still-uncompleted video project of Albert’s life. For Dad, it had become a tender tale. Dad very much wanted to meet Albert.

These deep-feeling conversations with Dad are some of the most precious to me. Dad was not one to get weepy but he would when discussing individuals he admired.

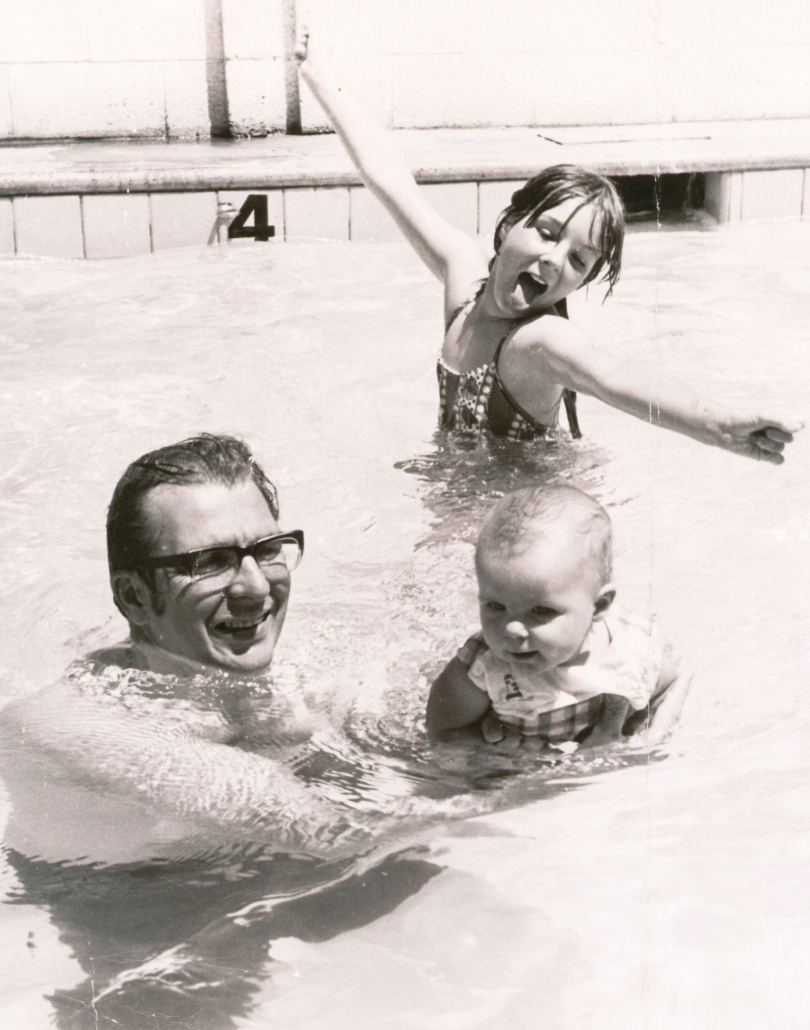

One he admired more than any other is my Mom.

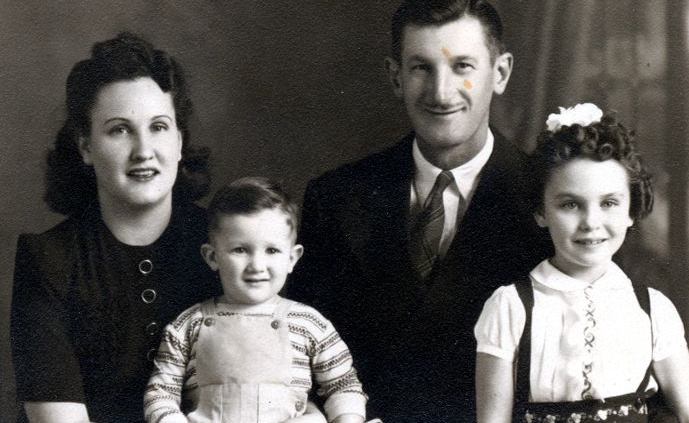

I was there with Dad in the weeks and days after Mom’s passing. Although we all knew Mom would be leaving I was shocked to see how much it threw Dad. He literally did not know what to do with himself when she left.

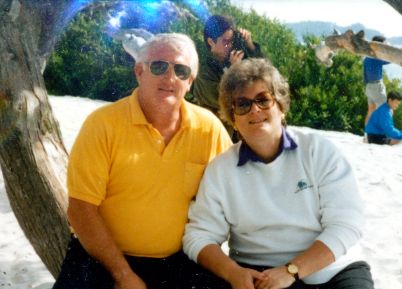

During my time with Dad we talked about Mom more than any other person.

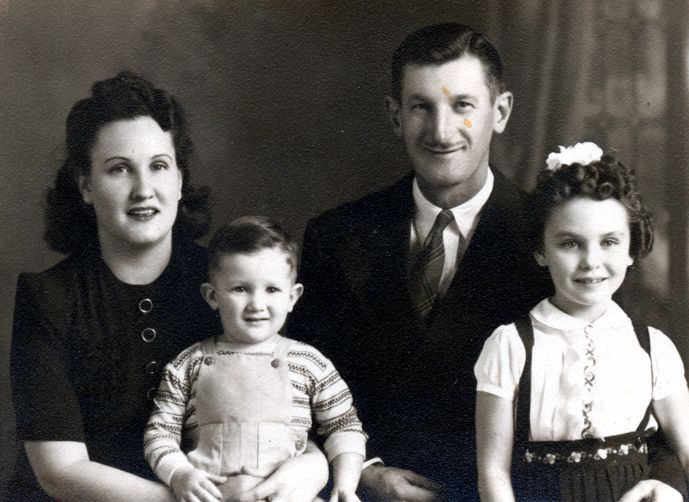

We talked about their courtship, their first years together and the many miracles of my Mother’s life that came in overcoming the challenges of her youth and the things she had to accept in marrying Dad.

Perhaps if only because he had nobody else to confess to Dad unloaded his private grief and regrets about his relationship with Mom from different parts of their lives.

These sacred moments were of a nature I cannot completely share. He did not have to share those things with me.

But we also shared my feelings about Mom, and experiences I had with her he knew nothing about. It was liberating in a way to be able to share things about Mom that Dad knew nothing of.

One of the things I have not publicly shared of my time with Dad was Mom’s constant presence in that house. It was a palpable thing, to me, and I told Dad often when I felt her influence.

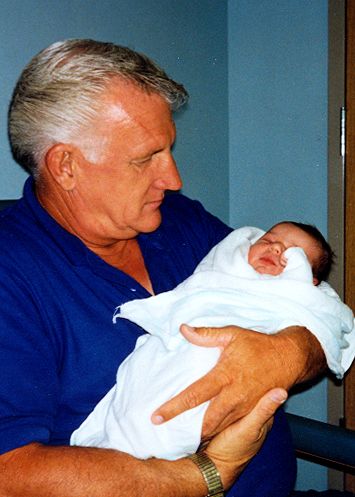

In October 2021, our daughter was expecting a baby and she wanted her Mom home for the birth. Sandy was again out in California and, as was our routine, I had my sisters care for Dad while I ran out there to bring Sandy home over a weekend.

It was a Friday night, after work, and I was rushing to get on the road so I could get back as soon as I could. My sisters were coming over, and bringing food, so I knew Dad was in good hands. But I was out of time and things were undone, such as the dishes.

Dad told me not to worry about them. He said he would do them, which was a ridiculous idea.

I toyed with texting my sister to ask her to do them and as I was entertaining those thoughts I heard my mom in my head say, “Get in there and do them, young man”. I simply could not leave the house without them done, so I did them.

Dad heard the water running and said, “What are you doing?” I told him that Mom told me I couldn’t leave without doing them and he laughed. “I’m serious, Dad”, I said.

“I know,” he said. “I feel her here too.”

Dad never had profound spiritual experiences. Ever. We talked about that a lot. My Mom had a lot of them and I think it bothered Dad a little that he never did.

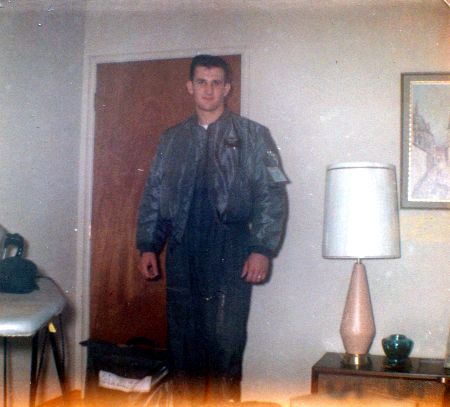

In fact, Dad confessed to me during one of our conversations that he knew at about the age of 10 that Joseph Smith was a prophet. He didn’t read about it, he didn’t have a vision or any kind of experience. He just knew.

From the very beginning, Dad said, he felt what he was taught by his parents, primary teachers and countless others he associated with at Church was right and true.

That is a spiritual gift, as valid as any gift my mother had with her many manifestations as a convert to the Church.

Mother’s living and dying experience showed us how close the other side is as we prepare to leave this life. I think each of us as her children saw moments of these during her final days. Dad had no such experiences, though he really wanted them.

I know this because he would have told me if he had them. I often asked him and he always said no – no dreams, no visits, no visions.

Were there things I learned from my father I did not know during these days? Yes, there were many.

I will share them as I tried to record them – as each of these histories that Dad was working on somehow gets finished.

I cannot write them as he would have.

We talked about this too. Dad always claimed I was the better writer but Dad is a better organizer of thoughts. Some of what I have from him are just outlines, but they are brilliantly organized.

These days I don’t think of Dad very much as a man with cancer. In fact, I can hardly think of Dad as being passed on. He’s very much alive to me.

In recent weeks, as I have tried to find motivation to step up my family history efforts again, I have come to two unexpected decisions about the direction I am going to take. I won’t share those decisions yet but I will share that I know when my Dad is with me on something.

During our time together we came to think similarly, especially when a decision needed to be made. I learned that part of caregiving with Dad was to not make decisions for him. I learned to just accept what he wanted, especially as it related to his health.

On the night he died the last person he spoke to was Joann, who had called to check up on him. They had a really good conversation and later Joann told me how surprised she was in the strength of Dad’s voice. But not long after they hung up Dad got really sick – as sick as I had ever seen him.

He was just two days away from his final treatment and these were always days of anxiety because his “episodes” were more frequent and dangerous. I gave him injections, which helped him through these episodes, every six hours.

As I was giving him his 9pm shot he was holding his hands on his chest. I asked him, “Dad, what are you feeling?”

He said, “I don’t know. This feels different.”

“Are you having a heart attack, Dad?” I asked, knowing this would likely happen at some point because the rush of hormones caused by his cancer would damage and weaken the heart suddenly.

“No, it’s not that” he said.

Within a few minutes the shot did it’s thing, and he seemed recovered. He fell asleep as I watched him from the chair in the corner of the room, listening to his breathing. In about an hour, Dad woke up and wanted to use the restroom.

So, as was our routine, I positioned his walker by the bed, he stood up, and made his way into the restroom. He was in there only a few minutes and I heard him pound on the wall.

This was also a routine we had long established. That pounding on the wall happened when he was starting to black out and couldn’t use his voice to call me. I ran in there and caught him at the last second, just before he went down. He came to, and we were able to get him back to bed.

“Dad,” I told him. “No matter what, you need to let me be with you the next time you get up, okay?” He nodded, then said he was okay and fell back asleep.

Around midnight I heard him get up. I went running back to the bedroom and again caught him just as he was going down. When he came around again, I said, “Dad, we agreed you wouldn’t try to get up without me.”

“Oh yeah,” he said. “I forgot.”

Just after he said this he started to flush again and I had to lift him back into bed. Even though it had been only three hours I was told by the doctor that in a moment of distress I should give Dad another shot. He was clearly in distress to me so I gave him another shot. Dad came to as I was finishing.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

Again, Dad was clutching his chest, and he was breathing heavily.

“Dad, do I need to take you in? I think you’re having a heart attack. Should I take you in or call 911?”

“I’m not going back there, son. Not ever. I’m fine. I’ll sleep.”

Those were his last words to me. The shot stopped his distress and he stabilized and fell asleep. I stayed in there until 1:10am and felt pretty confident he was safe.

So I laid down, setting my alarm for 3:00am to give him his next shot.

At that time I found him – gone.

He had gotten out of bed, went to the bathroom, and had his walker up against the side of the bed. I think he died as we all imagined he would – on his feet. He had fallen to his knees and was draped over the front of his walker, his long arms stretched out on the bed in front of him.

I immediately called 911 but I knew he was gone. I knew. I did everything they told me to do and within minutes the apartment was filled with first responders.

When the first of them arrived he offered to take over CPR for me and it was only then that I realized Toby was still in his cage, literally a foot from Dad’s head. He had witnessed everything and never made a sound. I picked him up, crate and all, and took him out to the other room. It was out there that I heard the lead first responder ask if Dad had an advance directive, which I had forgotten all about. I answered yes, they read it and they stopped working on Dad.

I was in shock. I should not have been, but I was. I never had a feeling that Dad would leaving so soon. But as I spoke with the medical examiner, explaining what I could of Dad’s condition and medications, I came to accept things in a very clinical sense.

Of course it was the cancer. Of course it was a heart attack or a massive stroke or something. Everything I had learned about how this cancer took lives had passed right in front of me.

As the first responders packed up their gear, the police officer assisting had called the mortuary and they would come soon to pick up the body. They all left and Toby and I were alone, with Dad’s body back on the bed. Toby jumped off my lap and headed back towards the bedroom – then stopped when he got to the door, hung his head and slowly walked back and jumped in my lap again.

The mortuary came, and in a scene reminiscent of my Mom’s passing, they left a rose on the bed as they took the body away.

It was only after they left that I completely lost it. I let out a cry from deep within as Toby tried his best to comfort me. That sacred moment of mourning was necessary and I knew Dad was there for it. I don’t know how I knew it. I just did. I know my Mom was there for it, too.

All that I thought, all that I felt, all that I had been through not only that night but for those many months with Dad were important and special and tragic and life-changing for me.

For days, weeks and months afterwards I gave in to so many thoughts holding myself responsible for Dad’s experience that night.

I couldn’t escape it.

I should have seen the signs, I should have taken him in, I should have done whatever different so that the outcome could have been better.

Slowly I came to realize it couldn’t be better. Dying is part of living. We all go through it, however differently.

That Thanksgiving, that Christmas and that long winter were not easy months for me. I prayed for relief from the guilt.

Then Dad gave me a reminder from the other side.

Sandy’s Dad was in the final months of his life. He was fighting dementia.

Sandy had become very tender with my Dad in his final months. She would come home but stay with me at Dad’s place – so she was never really “home” during the past couple of years. She wanted to support me, yes, but she also wanted to help Dad in any way she could. For Dad, that meant food, even though most foods Dad had issues digesting due to his illness. But Sandy would bake and if it was cookies or pies or meals of any kind Dad loved the love put into the food.

Dad gushed over her, almost to the point of embarrassment at times. But he really, really loved her for being my companion. He knew the purity of her heart. Those months with Sandy coming in and out were precious to us all as it gave us opportunities to share with each other that life previously had not. In Dad Sandy had another she could confide in about her own father. These two men could not have been more different. But Dad knew what Sandy’s father meant to her and honored it in a way that Sandy needed.

Sandy would sometimes hear the conversations Dad and I would have and she’d just listen knowing we were having never-to-be-had-again moments. It was a sacred time with a lot of love.

Part of that love came from Sandy’s Mom, who would send a card now and then and, when I would go to California, she’d look me in the eye and say, “Jeff, how is your Dad doing?” I tell her the latest and she’d always say, “You tell him we’re praying for him and that we love him.”

Dad would do the same. Constantly. In fact, Dad would say he could little complain about his trials since Sandy’s Dad was having it so much worse. It meant a great deal to me to hear those prayers and feel that support going back and forth.

Several months after Dad passed Sandy again headed out to California. Her Dad had progressed to the point where each trip she didn’t know what she would see once she got there or if her Dad would even be there when she returned. Every trip was a heartache, coming and going.

At one point, some tough news arrived and Sandy was distraught. It was during this moment I came to understand that maybe some of what I went through with my father would be of service to my wife as she experienced things with her Dad. In that moment of contemplation, I felt Dad’s presence. I have felt it at other times too, always around one family situation or another. The connection I felt with Mom while with Dad was familiar and now I feel it with Dad, too.

Sandy’s father passed in September 2022, about ten months after Dad died. And, yes, I can not shake the grief my dear wife still deals with but I can understand and listen as she works through it.

I cannot help but think of these two family patriarchs – her Dad and my Dad – now on the other side. They share grandchildren. They share Sandy and me. Of course they remain concerned and engaged.

Do they influence us, as they say our ancestors do? Are they embedded in our lives, as they say our ancestors are?

My answer is yes. My Dad is still my Dad.

I know these two decisions most recently made in relation to my family history work are something Dad is aware of and approves of. I have felt the presence of both Sandy’s dad and my dad as we have gone through some new trials these past six months as well.

The point I guess I’m trying to make in more than 4000 words here is that my Dad’s history isn’t yet complete. He’s still making that history. And we are as well adding to his history by the things we do as his family.

Dad’s birthday is just a marker on a thing of this world. Where he is now I’m not even sure that date carries any meaning.

But I like marking his birthday. It’s a happier marker than recalling the day of his death.

Well, what happened that day and the months leading up to it have now been sufficiently recorded. Additional memories may still come up, of course. But the tale has been told and we can focus going forward on how he lived.

For that I am very grateful.