Tag Archive for: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

The Deacon of Killingworth

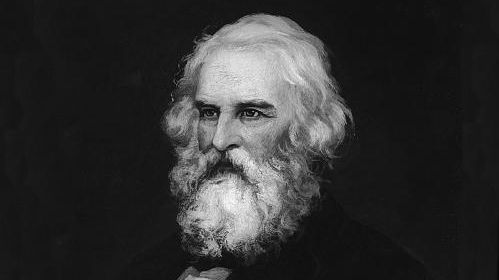

Last year I shared with you a family history connection we have with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow – great American poet and truly one of the “rock stars” of the 19th century.

Last year I shared with you a family history connection we have with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow – great American poet and truly one of the “rock stars” of the 19th century.

We share with Longfellow the common ancestors of John and Priscilla Alden.

Another common ancestor we share is “The Deacon”, as Longfellow referred to him in his famous poem, The Birds of Killingworth.

Cousin Henry Wadsworth Longfellow is famous for a lot of things.

He was very educated. He spoke ten languages and studied dozens more. He was not only a poet but also a famous educator, teaching for a time at Harvard.

His published works not only showcased his knowledge of history and literature but they reflected well his sensitive nature about things as personal as love and family.

As an artist, both then and now, he has had to endure the barbs of critics who felt his works were frequently too romanticized and filled with fantasy.

I’m no critic. I’m also no expert on the high-minded world of poetry. I cannot write it, much less understand it well when I read it.

But in studying the life of Longfellow I do know this: he knew his family history, whether talking about John Alden or The Deacon.

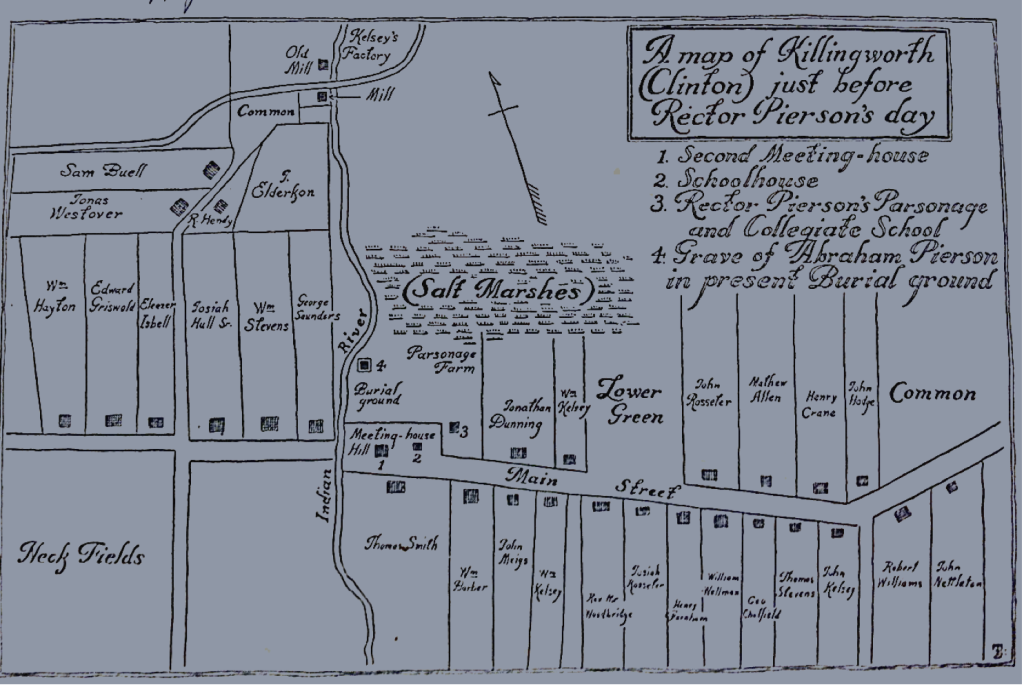

The Birds of Killingworth is a poem set in the very real village of Killingworth, Connecticut – a very important place in early American Westover family history.

It was, for a time, home to Jonah Westover, the first Westover in the New World.

In the poem the story is told of a town meeting held in Killingworth where the farmers implore town leaders to do something about the birds that were feasting on the farmers’ crops.

Even as the songs of those same birds wafted through the windows of the old church where the meeting was held the argument was made to kill the birds.

The town elders were riled up. The Squire, the Parson, and the Deacon were there, which gave weight to the proceedings.

Of the Deacon, Longfellow described him like this:

And next the Deacon issued from his door,

In his voluminous neck-cloth, white as snow;

A suit of sable bombazine he wore;

His form was ponderous, and his step was slow;

There never was so wise a man before;

He seemed the incarnate “Well, I told you so!”

And to perpetuate his great renown

There was a street named after him in town.

Arguments were made in the debate from every side but for the birds, well, “Hardly a friend in all that crowd they found”.

The town voted to kill the birds and as the poet tells the story they came to regret it. Without the birds the worms took over the crops and the insects devoured most of the grain and the leaves on the trees, leaving the fruit to be scorched by the sun.

The farmers and the town indeed learned the lesson of that balance to nature that the birds provided.

Many interpretations of this famous poem do not recognize Killingworth as a real place.

But Longfellow did.

Killingworth was a stopping point for Longfellow in his travels when he wrote The Birds of Killingworth in 1863. Why was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in Killingworth, Connecticut?

Because he knew it as an ancestral homeland.

If Longfellow knew anything, it was his family history.

His father was a lawyer and his maternal grandfather was a general in the American revolution as well as a member of Congress. Longfellow knew he was descended of at least four Mayflower Pilgrims.

When he was 15 he attended Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine – a college founded by his grandfather and his father was a trustee of the institution.

Longfellow was taught his family history and used his knowledge of his ancestors in many of his most famous works. They inspired him – even the Deacon.

The Deacon was Edward Griswold, town father of Killingworth, Connecticut and father to Hannah Griswold Westover, wife of Jonah Westover, the first male Westover in America.

Griswold was born in 1607 in Kenilworth, England, from which the name Killingworth is derived. He was born in a family rich in English history and famous for providing greyhounds for the King. He was educated and his family was connected.

Edward Griswold married in 1629 and with his wife Margaret had about five children before immigrating to the New World in 1639.

Edward brought with him younger brothers Michael, Francis and Matthew, all who would make historic contributions to the history of Connecticut and Massachusetts.

Edward quickly became prominent in the affairs of Windsor, Connecticut. He served as Deputy to the General Court from Windsor and was also Justice of the Peace of Windsor prior to 1663.

He was granted land from the King in Poquonoc (now Groton), about 4 miles west of Windsor, in 1642, but he didn’t move there until after the Indians were gone from the area. When it was safe, they settled the area with the families of John Bartlett and Thomas Holcomb in 1649.

His brothers Francis and George came to settle there soon after. His homestead consisted of 29.5 acres, bounded at the east by the Poquonoc River, the south and west-northwest by Stony Brook.

The house stood on the hill just to the north of the main road. Because of the potential dangers of the wilderness, the families were relieved of military duty so long as there was always a man available to stand as sentinel.

In 1663 Griswold was appointed to a committee charged with developing a new area near a place called Saybrook.

It took some time but within a few years Griswold had moved his family there, including new son-in-law Jonah Westover and his family. He helped to charter the foundation of a Church there and was named Deacon. In 1667 he was named deputy of Killingworth, a position he held nearly up to the time of his death.

It took some time but within a few years Griswold had moved his family there, including new son-in-law Jonah Westover and his family. He helped to charter the foundation of a Church there and was named Deacon. In 1667 he was named deputy of Killingworth, a position he held nearly up to the time of his death.

Over the course of his years there Griswold was influential in nearly every major civic action, collecting properties and settling claims with other area pioneers.

Edward and Margaret had at least a dozen children. As such, Edward sits as head of a very large family tree, with some 20 million plus people in his downline. As a prominent individual with fairly well documented history there literally thousands who have been working on his history.

I also believe, given his ties to the Puritan movement, that Edward Griswold had a very large influence upon the children of others.

I cannot prove it but I strongly suspect his ties to Jonah Westover pre-date the marriage of his daughter Hannah to Jonah. The year of their immigration and the year of Jonah’s ascension as a married man, a Freeman, and a property owner coincide very closely with the movements of Edward Griswold.

I believe Edward Griswold was as much a step-father and mentor to Jonah Westover as father-in-law. Their lives were that closely aligned. In both Simsbury and in Killingworth the Westovers were also neighbors to the Griswolds.

I don’t think Longfellow was plagued much by imagination in his poetry. I believe he educated himself on history of both places and individuals.

In fact, The Birds of Killingworth stirred the suspicions of experts long after Longfellow’s death. What was his inspiration?, they wondered.

“The Birds of Killingworth” is the only episode in Tales of a Wayside Inn that Longfellow had not adapted from an older textual source.

For many years readers suggested that Longfellow might have likewise based this tale, describing the massacre of pestilent birds by the citizens of the town in Connecticut, on some forgotten legend or historical incident.

Shortly after Longfellow’s death a literary sleuth wondered whether the tale originated on the other side of the Atlantic, since Killingworth got its name from Kenilworth, in England. One person even went to great lengths to write the town clerk in Kenilworth, England to see if ever there was a town vote about killing birds. None was found.

Nobody in the 19th century seemed to make the connection of Longfellow to Killingworth, though they never stopped trying.

In 1890 a publication called American Notes and Queries published a letter from Longfellow’s brother Samuel, who claimed that he found a newspaper clipping reporting a debate in the Connecticut legislature upon a bill offering a bounty upon the heads of birds believed to be injurious to the state’s farmers. It was from this not-so-famous debate that it was concluded that Longfellow had to have used it as his inspiration for the famous poem.

We know now that had little to do with it. Killingworth was a personal connection for Longfellow. While the story of the birds has no known basis in historical fact the characters within the poem were strikingly real when compared to what is known about Killingworth history — and Longfellow history (and, by extention, our history).

On Longfellow’s 100th birthday in 1907 journalist William E. A. Axon reported in The Nation that, a year before Longfellow died, he had written to him, asking “whether this narrative had any basis of fact or was merely the fantasy of a poetic brain”— and the great poet himself had replied:

The poem is founded on fact. Killingworth is a farming town, on Long Island Sound…of course, the details of the poem are my own invention, but it has substantial foundation of fact.

That fact was family.

Longfellow’s Family Story is Our Family Legend

The “Albert Smith Project”, as I’ve come to call it, has yielded so much interesting information there is just no way to include it all in the upcoming video.

Some of it is so compelling that I still feel a need to share it – including this story here.

Father Smith, as the citizens of Manti came to know him, was of the same generation and age as Electa Westover. He connects into the Westover line through the marriage of his granddaughter, Mary Ann Smith, to Arnold Westover in 1914.

In advance of the building of the Manti Temple Albert Smith paid a genealogist to find the names of his ancestors. This was way back in 1878, right around the time plans for a temple in Manti were announced.

It took years but when the names finally arrived Albert was pleased. The first was a batch of 400 names. Over the years as the dedication of the temple approached in 1888 Albert would eventually take more than 1400 ancestor names to the temple.

Albert was thrilled to learn of his heritage – especially now that he could recount it directly back to the Mayflower.

I can now count 11 direct ancestors on my family tree who were on the Mayflower. Among them are my 9th great-grandparents, John and Priscilla Alden – ancestors we share directly with Albert Smith.

Living in the relative isolated wilderness of Manti there is no doubting the need Albert had to pay someone to travel east to learn his genealogy in the late 19th century. He simply would not have had any way to locally do that research.

But he recognized right away the name of John Alden.

How could that be?

Perhaps it was through the work of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, a popular American poet of Albert’s time.

Longfellow is still known to many for his great works, including the touching story of the beloved hymn, I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day, based on his poem “Christmas Bells”. His poems sometimes told great stories, including Evangeline and The Song of Hiawatha.

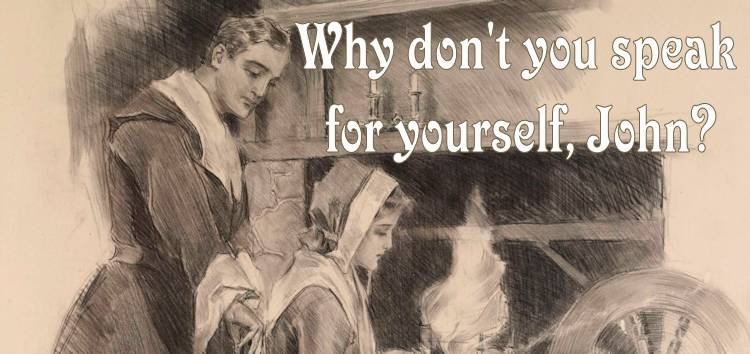

Longfellow is also a direct descendent of John and Priscilla Alden. In fact, one of his most beloved works was based upon an old family story featuring the romance of John and Priscilla Alden. It is called The Courtship of Miles Standish, written in 1858.

Historians to this day debate whether the story told by Longfellow of his grandparents is fact or fiction. Another descendant of the John Alden, Timothy Alden, first told the story of the Pilgrim love triangle in his book American Epitaphs in 1814.

Historians to this day debate whether the story told by Longfellow of his grandparents is fact or fiction. Another descendant of the John Alden, Timothy Alden, first told the story of the Pilgrim love triangle in his book American Epitaphs in 1814.

The story would become famous with Longfellow’s “epic poem” of the tale, a story he loved and struggled with for more than two years to write.

After it was published, Longfellow famously said of the story in 1858 “…it is always disagreeable when the glow of composition is over, to criticize what one has been in love with…”

In the poem, Plymouth’s military leader, Myles Standish, asks John Alden to court Priscilla Mullins on his behalf. This causes John to be torn between faithfulness to his “captain” and the longings of his own heart.

Of course, as the tale is skillfully woven, John and Priscilla fall in love and the dilemma reaches a climax as Priscilla famously mused, “Why don’t you speak for yourself, John?”

Longfellow’s attempt to balance a romanticized view of Puritan values and culture with an epic exaggeration of Standish’s heroism and exploits captured the imagination of American readers in the 19th century and made household names of John and Priscilla.

It is interesting to note the cultural impact the story would have on American history.

Longfellow’s poem came just a few years after the discovery of William Bradford’s written history of Plymouth Colony in 1854.

The poem was released just in advance of the Civil War, a time when holidays such as Christmas and Thanksgiving were just gaining a foothold in American cultural tradition as national observances.

Bradford’s history, coupled with Longfellow’s The Courtship of Miles Standish, advanced the recognition of Thanksgiving as a national holiday, although it had been celebrated in New England since the mid-1600s.

So popular was the poem in the 1860s, after Lincoln’s recognition of a national day of Thanksgiving, it became a fad of sorts to lay claim to pilgrim ancestry.

Northerners in particular — Yankees like Albert Smith — were thrilled to celebrate national history that was not centered in Virginia and as the nation recovered from the war their Victorian sensibilities were enamored with the Puritan ideals of moral rectitude, fair mindedness and hard work.

To claim an ancestor on the Mayflower somehow made one more American.

Albert Smith’s mother was an Alden – but that fact was never once mentioned by Albert as anything important until the 1880s – when it was perhaps more culturally relevant.

Whether the love story of John and Priscilla is true or not matters little now. Without them, without Longfellow, we have a little less known about America, about life as pilgrims and about all we celebrate at Thanksgiving.

I believe I will hold in reserve now the telling of this story – and the reading of The Courtship of Miles Standish – as a new Thanksgiving tradition in my home.

It is, after all, all about family.