https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/hannah.jpg

382

679

Jeff Westover

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/logo22.png

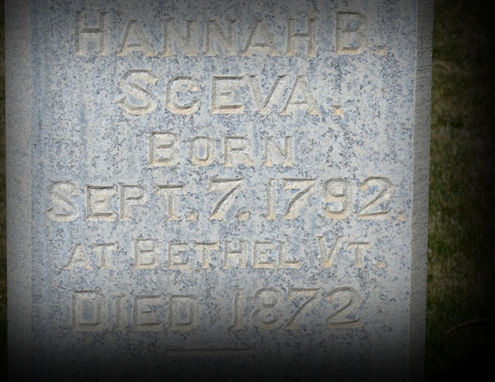

Jeff Westover2021-03-31 00:13:082024-03-03 16:09:44Hannah and Her Sisters

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/hannah.jpg

382

679

Jeff Westover

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/logo22.png

Jeff Westover2021-03-31 00:13:082024-03-03 16:09:44Hannah and Her Sisters

Colliding Family Histories

Note: I have always maintained that our efforts with this site…

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/longfellow1.jpg

280

499

Jeff Westover

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/logo22.png

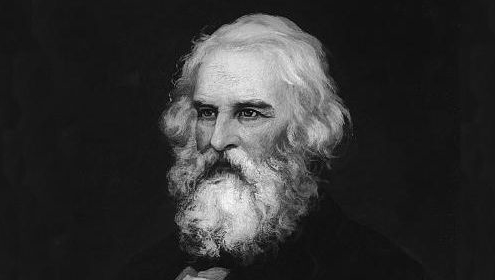

Jeff Westover2020-04-23 21:53:422024-03-03 16:07:38Family Crisis: Longfellow’s Trials

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/longfellow1.jpg

280

499

Jeff Westover

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/logo22.png

Jeff Westover2020-04-23 21:53:422024-03-03 16:07:38Family Crisis: Longfellow’s Trials https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/year-1856.jpg

844

1500

Jeff Westover

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/logo22.png

Jeff Westover2020-03-30 11:30:262024-03-03 16:07:10Family in Crisis: 1856

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/year-1856.jpg

844

1500

Jeff Westover

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/logo22.png

Jeff Westover2020-03-30 11:30:262024-03-03 16:07:10Family in Crisis: 1856 https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/saltlake1850s.jpg

321

800

Jeff Westover

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/logo22.png

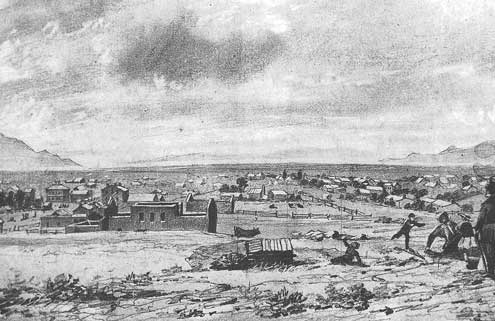

Jeff Westover2020-02-14 02:18:052024-03-03 16:03:08Consecrating All

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/saltlake1850s.jpg

321

800

Jeff Westover

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/logo22.png

Jeff Westover2020-02-14 02:18:052024-03-03 16:03:08Consecrating All