The Value in Re-Plowing Old Ground

/

0 Comments

It has been an interesting time for working on family history.…

My Cousins, My Neighbors

Years ago, when we moved into our present home, we met the nextdoor…

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/evie1.jpg

628

1200

Jeff Westover

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/logo22.png

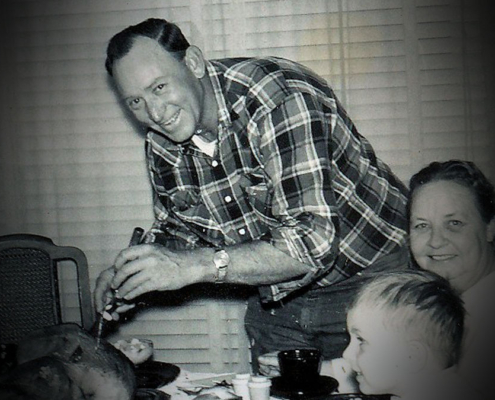

Jeff Westover2022-05-23 17:35:112024-03-03 16:16:48Memories of Aunt Evie

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/evie1.jpg

628

1200

Jeff Westover

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/logo22.png

Jeff Westover2022-05-23 17:35:112024-03-03 16:16:48Memories of Aunt Evie

The History of Pascal Henry Caldwell

In March of 2022 we marked the 100th birthday of Pascal Henry…

Electa Jane Westover Emett

Last year when I traveled with Dad, LaRee and Will on our “cemetery…