Westovers of the American Revolution

We received an email requesting more information about the John Westover family of Sheffield, Massachusetts of the mid-18th century.

The inquiry was specifically about which of the many sons of John and Rachel Westover were loyalists and which were colonialists.

It is an interesting question simply because it was the American Revolution that really started the spread the Westover family across North America.

The answer to that question is quite complicated, however.

Living in those times in New England tried the loyalties of nearly everyone. It was a dangerous time.

The key fact to bear in mind lies with the patriarch of the family, John Westover. He was the clerk of the Church of England in Sheffield. The Church was headed by the King of England. His loyalty had to be to King and country.

But by the mid-1770s his sons were grown men.

The sons of John and Rachel Westover were, in order of age: John Jr., Job, Moses, William, Noah and Amos.

Many of these sons served in the colonial side during the American Revolution and are identified in historical records as patriots:

John Jr — 3rd Co., First Regt. of Berkshire Co. Militia, 11 Jul 1776

Job — 3rd Co., First Regt. of Berkshire Co. Militia, 11 Jul 1776

Moses — In the 3rd Co., 1st Regt., Berkshire Co. Militia, 11 Jul 1776. He was a private in Capt. Enoch Noble’s Co., Col. John Ashley’s Regt., Berkshire Co. Moses entered service on 1 Aug 1777 and was discharged 20 Aug 1777. The Company marched to Bennington, Vermont by order of Brig. Gen. Fellows and the Committee of Saftey at the request of Gen. Stark.

Noah — 3rd Co., First Regt. of Berkshire Co. Militia, 11 Jul 1776.

However, despite their service record, each are mentioned in various histories as loyalists to the British Crown.

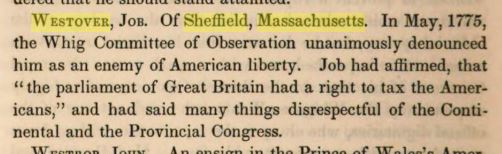

For the video titled Brothers we referenced several books, including an 1847 publication by Lorenzo Sabine titled The American Loyalist: Or, Biographical Sketches of Adherents to the British Crown in the War of the Revolution. Below is a snip of all that is written of Job Westover:

Another volume, this one titled American Archives: Consisting of a Collection of Authentick Records, State Papers, Debates, and Letters and Other Notices of Publick Affairs, the Whole Forming a Documentary History of the Origin and Progress of the North American Colonies; of the Causes and Accomplishment of the American Revolution; and of the Constitution of Government for the United States, to the Final Ratification Thereof (They had insanely long titles in those days), written in 1839, the actual notes of the committee action noted action against three of the Westover family: John, Job and Noah.

That record agrees with the other accounts listed here but it does not give any mention of the activity or disposition of action against Noah Westover.

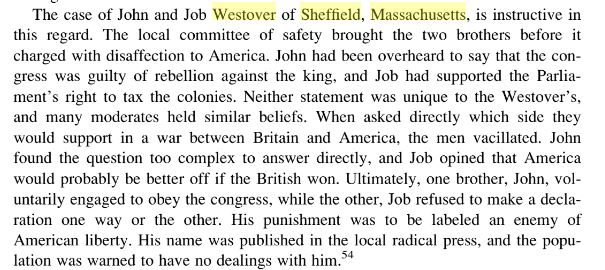

Another book, A History of War Resistance in America by James M. Volo, gives us a little more information:

Moses Westover’s history is a little more well known. What we learn of Moses comes from histories written in and about southern Canada, where many New England loyalists fled to after the Revolution.

From a book titled Contributions to the History of Eastern Townships: A Work Containing an Account of the Early Settlement of St. Armand, Dunham, Sutton, Brome, Potton, and Bolton, with a History of the Principal Events that Have Transpired in Each of These Townships Up to the Present Time, published in 1866 by Cyrus Thomas, we learn:

Moses Westover, in 1796, settled in North Sutton, about three miles east of the place where the settlers named above took up their residence. A part of the lot on which he pitched is now owned by Roswell and Stephen Westover, his grandsons. Mr. Westover was a loyalist. He lived in Sheffield, Massachusetts, at the opening of the revolution, but finding his life in jeopardy in that place, he fled and came to Canada. Previous to coming to Sutton he lived at Caldwell’s Manor. He was granted two lots of land by the British Government on account of his loyal principles; one was located in Stanbridge; the other was the one on which he settled in Sutton.

This nice bit of history is significant because it was from Moses that the Canadian branch of the Westover family was born. He had a large family and was quite prominent in that area.

Moses’ brothers would also have large families. His brother John Jr moved to Canada near Moses.

Job, the one identified as the enemy to liberty in Sheffield, actually stayed there after the war and raised his family. Some of his children would leave Sheffield to raise large branches of the family elsewhere. It was his son, Job Jr, who left for Missouri and founded the family branch there. His son, Luther, had 10 children of his own including William Westover, who would later in life become a founding father of some fame in Bay City, Michigan.

William Morton Westover, another son of John and Rachel, born in 1746, does not have much of a historical record. We do not know how long he lived, if married or if he lived long enough to see the American Revolution like his brothers.

Noah Westover would stay in New England, marrying around the time of his military service. He and his wife raised 5 children – 1 son and 4 daughters. This family would spread further into New England and the American Midwest.

Amos Westover – father to Alexander and grandfather to our Edwin Ruthven Westover – never served in the war. He did follow his brothers into Canada for a time but migrated back to the United States through Vermont, eventually making his way to Ohio. All of his children moved west with the Mormon migration in 1848.

The children of John and Rachel Westover included 4 daughters, too: Rachel, Abigail, Joanna and Rhoda.

The two oldest girls either died in infancy or as small children. Joanna married in 1763 to Moses Ashley Eggleston and they had two children. Daughter Rhoda lived a very long life of 96 years, bringing five grandchildren to the Westover family, who settled between New York and Vermont.

In all, John and Rachel Westover had 10 children and 47 known grandchildren. Their youngest grandchild was John Race, who was born to Rhoda in 1810 and died in 1895.

These three generations – John and Rachel, their children and their grandchildren – covered roughly 190 years on this earth. But more impressive is the distance and the number of places where they settled all over North America. From Massachusetts to southern Canada, westward to Michigan, Wisconsin, Ohio and then to Utah, Idaho, Arizona and California, and also all over New England – we are trying to map it all.

But most interesting and central to it all is the American Revolution. That was the trigger event and it was a big one.

Other events would further spread out the family. We will get to those in time. But in my view there is still a lot of work to do to document the many histories of each of these individuals, starting with the children of John and Rachel. We have a start in that we know when they lived, who they married and the children they had.

But we don’t know much of their individual stories. I believe each of these stories are compelling – if we can learn them.

If you are a descendent of the children of John and Rachel Westover, we’d love to hear from you. With grandchildren of theirs living nearly until the 20th century the possibility exists that there may be photos. Perhaps written diaries survived. Maybe something out there exists that can tell us more of their story.

We hope you might share.

Pandemics in Our Family History

January of 2020 will go down in history for the outbreak of what is called Coronavirus. As of this writing it is not yet a pandemic but it is expected to become so, despite a now worldwide effort to deal with the outbreak.

Will it have an effect upon our family?

It is a good question because such events in the past have actually changed the course of history for many families. It is the kind of event that can affect generations.

Such was the case with my great-grandmother, Susan Carson Welty.

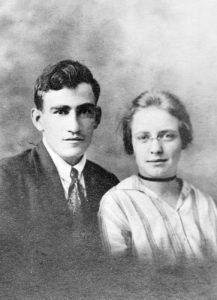

Born in 1898, Susie, as she was called, was the first born of 11 children of Kit and Effie Mae Carson.She would marry Alfred Welty at the age of 17. Her first child, my grandmother, Winifred, was born in 1917 and her second child, Norman, would be born in November of 1918.

Susan Carson Welty died at the age of 20 just about a month after Norman was born in December of 1918. She died of pneumonia, an after effect of the Spanish flu, which was ravaging the world around that time.

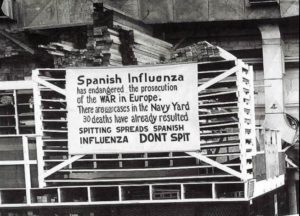

According to the CDC, the 1918 flu pandemic was the most severe pandemic in recent memory. It began in January of 1918 and is estimated to have affected a third of the world’s population at the time. As it ran its course more than 50 million people died, about 675,000 in the United States.

Great grandmother Susan C. Welty was one of the those who died of the Spanish Flu. Her passing made a widower of husband Alfred at the age of 23, who would pass just four years later due to “causes of diseases”.

One of the hallmarks of the 1918 pandemic was its devastation to those ages 20 to 40 years of age, a very unusual thing for a usually healthy age group. Many died right after the onset of symptoms while others in the age group died later after long lingering affects took their toll.

It is difficult to imagine how much this pandemic affected nearly everyone.In America alone one in every three people contracted the flu. Complicating factors was that the flu actually came in “waves”, this first hitting in the winter and spring of 1918.

It subsided over the summer but then returned with a vengeance in the fall of that year.

It hit so hard that fall there was a national shortage of caskets and newspapers in nearby Elmira, New York were showing ads from the City of Philadelphia seeking embalmers for hire.

Newspapers blamed the spread of the disease on soldiers returning from Europe during the war. On September 27th it was announced that “all draft troop movements were deferred” due to the influenza outbreak.

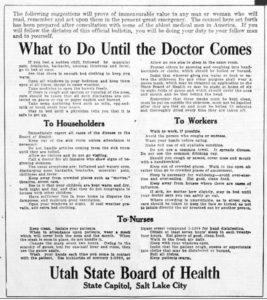

There were, as there is now, a large variety of steps people could take to prevent getting the flu.

The City of Elmira Health Officer, Dr. R.B. Howland, warned against over-eating.

“People who are inclined to eat heartily are prone to colds and a cold may bring on influenza.” He also recommended more stringent measures in case of whooping cough, “the home must be placarded and the individual having the disease must wear a red band on the arm when outside the house the band to bear the words, “Whooping Cough.”

Articles began to run in the Elmira papers with headlines, “Spanish Influenza, What It Is and How It Should Be Treated.”

The Elmira Herald reported about Vicks Vapo-Rub, describing its origin and application, noting that Vicks was “comparatively new to New York State” and that over six million jars were sold the previous year. Catarrhal Jelly was promoted as was Horlick’s Malted Milk — “the diet during and after influenza.”

On Oct.15 the Herald announced, “The lid is on. Elmira is closed to prevent further spread of Spanish Influenza.”

The night before a “Quarantine Order” had been declared by the Board of Health. The Order read: “all theaters, churches and Sunday schools, public, parochial schools and kindergartens, public libraries and art galleries, pool and billiard rooms and bowling alleys, all places where public meetings of every name and nature including meetings of fraternal, social and labor organizations are held public and private dances, all public funerals to be discontinued, all business houses and mercantile houses in the City of Elmira to discontinue any special sales of any article or articles, that various hospitals restrict visitors, that people overcrowding street cars and that all persons refrain from visiting homes or other places where there is sickness.”

Street cars were to be fumigated and disinfected every 24 hours. “Coughing and sneezing in public places” were to be considered a “misdemeanor in the future” and would be “punishable by law.” The same was true for “the practice of visiting homes where there is illness.”

It was reported that since the quarantine went into effect on Oct. 15, Elmira was visited by 2,740 influenza cases causing 68 deaths and 155 pneumonia cases resulting in 20 deaths.

Elmira turned to celebrating the armistice and the joy of returning soldiers, but influenza lingered. On Dec. 13, 1918, the Star-Gazette reported that the “Board of Health realizing that Elmira is not free of prevalent disease orders that all homes having influenza patients be quarantined two weeks.”Susan Carson Welty died on 12 December 1918.

As the mortality rates soared, so too did the willingness to try something, anything, to save themselves and their loved ones from a horrible death.

While attempts to develop a vaccine against Spanish flu floundered, doctors pioneered other methods to care for its victims, from the “rooftop cure” where patients were exposed to the elements to an experiment with potassium permanganate on British public schoolboys.

From the apparently innocuous first wave during the early spring of 1918 to the escalating second wave of Spanish flu that gripped the world in the later months of the year, daily newspapers carried an increasing number of advertisements for influenza-related remedies as drug companies played on the anxieties of readers and reaped the benefits.

From the Times of London to the Washington Post, page after page was filled with dozens of advertisements for preventive measures and over-the-counter remedies.

“Influenza!” proclaimed an advert extolling the virtues of Formamint lozenges. “Suck a tablet whenever you enter a crowded germ-laden place.”

Another advertisement announced “as Spanish Influenza is an exaggerated form of Grip,” readers should take Laxative Bromo Quinine in larger doses than usual, as a preventive measure.

For those who had already succumbed, Hill’s Cascara Quinine Bromide promised relief, as did Dr. Jones’s Liniment, previously and mysteriously known as “Beaver Oil” and intended to provide relief from coughing and catarrh.

Demand for Vick’s VapoRub, still popular today, was drummed up by press adverts warning of imminent shortages: DRUGGISTS!! PLEASE NOTE VICK’S VAPORUB OVERSOLD DUE TO PRESENT EPIDEMIC.

Americans were informed that it was their patriotic duty to “Eat More Onions!” as part of a “Patriotic Drive Against the ‘Flu.’ ”

An American mother took this suggestion to extremes, and fed her sick daughter syrup made from onions before wrapping her in onions from head to toe. Fortunately, the outcome was successful and the child survived.

Conventional medical advice for the treatment of influenza included morphine, atropine, aspirin, strychnine, belladonna, chloroform, quinine, and, disturbingly, kerosene, which was administered on a sugar lump.

Alongside these, folk remedies thrived. If a product from the drugstore failed to alleviate the symptoms, many patients and their families turned to more traditional methods.

One popular remedy in South Africa was to place a block of camphor in a bag and tie it around the patient’s neck. One eight-year-old girl, who was taking no chances, announced that she was wearing a camphor bag around her neck “to keep off the Germans.”The practice was so widespread that, over half a century later, an elderly South African lady in a nursing home, who had survived the 1918 outbreak, refused inoculation against the 1969 epidemic of Hong Kong flu. “Not for me,” she maintained. “I still have my camphor bag.”

In North Carolina, young Dan Tonkel had taken to wearing a bag of asafetida around his neck, in the belief that the stinking extract would protect him. “It smelled to high heaven,” he recalled. “People thought the smell would kill germs. So we all wore a bag of asafetida and smelled like rotten flesh.”

In Philadelphia, Harriet Ferrel was rubbed with tree bark and sulfur, and forced to drink herbal teas and take drops of turpentine and kerosene on a lump of sugar. Harriet was also subjected to the asafetida treatment but was philosophical: “We smelled awful, but it was okay, because everyone smelled bad.”

Robert Graves’ “Welsh gypsy” housemaid had an even more unusual form of protection, consisting of “the leg of a lizard tied in a bag around her neck.” She was the only person in the Graves household who did not develop Spanish flu.

Whiskey had always been a traditional remedy for colds and influenza, and whiskey prices soared in the United States during the epidemic.

In Denmark and Canada, alcohol was only available by prescription, while in Poland brandy was regarded as highly medicinal.

One brave soul in Nova Scotia recommended fourteen straight gins in quick succession as a cure for Spanish flu. The result of this experiment was unknown; if the patient had survived he had doubtless forgotten the proceedings entirely.

In Britain the Royal College of Physicians stated that “Alcohol Invites Disaster,” a conclusion which was ignored by many. The barman at London’s Savoy Hotel created a new cocktail, based on whisky and rum, and christened it “the Corpse Reviver!”

In the universal panic of the Spanish flu epidemic, many believed that the air itself was poisonous.

One woman in Citerno, Italy, sealed up her house so effectively that she died of suffocation.

Lee Reay of Meadow, Utah, recalled one family who sealed their house up. They plugged keyholes, sealed the windows, and even closed the dapper on the stove.

Roy Brinkley’s father, a sharecropper in Max Meadows, Virginia, decided that fresh air could be fatal during the epidemic and sealed up his wife and four children in one room. The family spent seven days sitting around the wood-burning stove until it caught fire. As his family fled the house and took refuge in the vegetable patch, Brinkley was convinced that the fresh air would kill them. For the rest of his life, Roy remembered a sudden rush of fresh air and the sight of cabbages, as big as washtubs. But, once outside, the entire family soon recovered.

The all absorbing nature of the pandemic was felt by family all over. No part of the country was spared. For most, public life kind of stopped as gatherings of all types were avoided.

In Mendon, Utah, the funeral for Ann Findley Westover was limited to just 15 minutes and attendance by only healthy individuals. The town history of Mendon mentions her funeral as a particularly unjust event that denied “Sister Westover” a proper memorial.

For the Westovers in Rexburg, who were no strangers to the effects of viruses in their history, the little community saw the flu arrive with the fall weather.

While the local paper reported that there was “no occasion for panic” due to the flu the article went on to justify the town’s quarantine. Schools, churches, movie theaters and all public gatherings of every kind were prohibited.

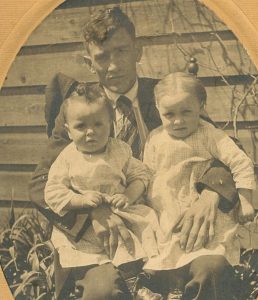

It was during the time that little Verle George Westover, third son of Arnold and Mary Ann, was born. He would live only six months. It is not known if the family ever caught the flu or if it was a contributing factor in his passing.

If records of past health emergencies existed I am sure we would see how such events affected other members in our family.

It is not known for sure but the devastating events of 1714 to the Westover family in Simsbury, Connecticut was likely caused by a disease. Prevalent at the time were fights against small pox.

In 1713-1715 all of New England suffered from a nasty outbreak of the measles. Thousands died, especially children.

Whatever it was that caused the sadness of May 1714 with the Westovers fully affected future generations. Lost during that event was Jonah Westover, Jr, who was by then patriarch of the Westover family.

His three youngest sons – Jonah, Nathaniel and John – were taken in by his brother, Jonathan Westover, who would raise them as his own and with his own after he married a few years later.

Whatever happens with this new Coronavirus – whether it spreads or fizzles – has the potential to affect family going forward for generations.

Will we be quarantined? Many don’t think so but to 11 million people so far in the city of Wuhan, China that is already a reality.

Will there be a variety of advertised cures? Will there be profiteers emerge on account of the crisis?

No doubt. We already seen ample evidence of that on social media.

Such is the stuff of life. Such is the stuff of family. We are not really immune from the disease or the societal reaction to it.

Our past generations have been tested by it. Chances are we will be as well.

Westover Family History on the Mayflower

The year 2020 marks the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower. No doubt we will be hearing a lot of history related to this anniversary.

The pilgrim story of the Mayflower began in the summer of 1620. But after several false starts the actual voyage of the Mayflower did not get underway until September 6th. It took 66 days or until November 9th for the Mayflower to arrive.

Plymouth was never intended to be their destination. But given their late departure and the rough seas along the Atlantic coast of the New World they ended up deciding, on Christmas Day 1620, to make their Cape Cod landing site of Plymouth as the site of their permanent plantation.

Here are the direct line ancestors we can count who came on the Mayflower:

William Mullins (10th Great Grandfather) – via the Westover-Smith-Alden lineWilliam was born in 1572. William brought his wife Alice and children Priscilla and Joseph on the Mayflower; he also brought over 250 shoes and 13 pairs of boots, his profession being a shoemaker. He died on 21 February 1620/1, during the first winter at Plymouth, as did his wife and son Joseph as well. His original will has survived, written down by John Carver the day of Mullins’ death. In it he mentions his wife Alice, children Priscilla and Joseph, and his children back in Dorking, William Mullins and Sarah Blunden.

Resolved White (10th Great Grandfather) – via the Westover-Riggs-Snow line

He was born 9 September 1615 in England to William White (1590-1621) and Susanna Jackson (1592-1664.) He came to America on the Mayflower with his parents in 1620, being one of the children on board the Mayflower to survive.The Whites are believed to have boarded the Mayflower as part of the London merchant group, and not as members of the Leiden Holland religious movement. He was raised by step-father Edward Winslow following the death of his father William and remarriage of his mother in 1621.

They moved to Marshfield in the 1630s and later moved to Scituate where he married Judith Vassall, the daughter of William and Ann King Vassal. Resolved White moved his family back to Marshfield in the early 1660s and Judith died and was buried there on 3 April 1670. Resolved then remarried to widowed Abigal Lord in 1674 in Salem. He was a soldier in King Philip’s War of 1676, and became a freeman in Salem in 1680, before moving back to Marshfield a couple years later. He married Judith Vasssal 8 April 1640 at Scituate, Plymouth, Massachusetts.

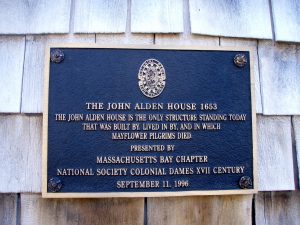

John Alden (9th Great Grandfather) – via the Westover-Smith-Alden line

John Alden was born in England about 1599 and died 12 September 1687 at the age of 88 or 89 Duxbury, Plymouth, Massachusetts.. He was a cooper by trade and hired on as a “Mayflower” crew member in that capacity at Southampton. The conditions of employment permitted him to either remain in America or return as a crew member to England. He chose to remain in the New World. He was one of the forty one signers of the Mayflower Compact.It is said that John Alden was the first Mayflower passenger to set foot on Plymouth Rock. He was also one of the founders of the Plymouth Colony and the seventh signer of the Mayflower Compact. Distinguished for practical wisdom, integrity and decision, he acquired and retained a commanding influence over his associates. Employed in public business he became the Governor’s Assistant, the Duxbury Deputy to the General Court of Plymouth, a member under arms of Capt. Miles Standish’s Duxbury Company, a member of Council of War, Treasurer of Plymouth Colony, and Commissioner to Yarmouth.

Priscilla Mullins (9th Great Grandmother) – via the Westover-Smith-Alden line

Priscilla Mullins was born probably near Guildford or Dorking, co. Surrey, England, to William Mullins. She came on the Mayflower to Plymouth in 1620 with her father, brother Joseph, and mother Alice. Her family, herself excepted, died the first winter. She was shortly thereafter, 12 May 1623, married to John Alden, the Mayflower’s cooper, who had decided to remain at Plymouth rather than return to England with the ship.They John and Priscilla lived in Plymouth until the late 1630s, when they moved north to found the neighboring town of Duxbury. John and Priscilla would go on to have ten children, most of whom lived to adulthood and married. They have an enormous number of descendants living today.

The romance of John and Priscilla Alden was made famous in later years. You can read about that here.

Edward Winslow (11th Great Uncle) – via the Westover-Riggs-Snow line

Almost everything we know about the first Thanksgiving comes from a letter written by Edward Winslow written in December of 1621.Born in England in 1595 Winslow moved to Holland in 1617 where he united with John Robinson’s church at Leiden, and in 1620 he was one of the Mayflower pilgrims who emigrated to New England. His first wife, Elizabeth (Barker) Winslow, died soon after their arrival at Plymouth. In May 1621 he married Mrs. Susanna White, the mother of Peregrine White (1620–1704), who was the first child born among the New England colonists. Winslow’s marriage to Susanna White was the first in New England.

Winslow was delegated by his associates to deal with the Indians in the vicinity (the Wampanoag) and succeeded in winning the friendship of their chief, Massasoit. He served as a member of the governor’s council from 1624 to 1647, except in 1633–34, 1636–37, and 1644–45, when he was governor of the colony. In 1643 he was one of the commissioners of the United Colonies of New England and on several occasions was sent to England to represent the interests of the Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies.

Winslow was a figure that was featured prominently in William Bradford’s journal and there is much written history about the man to be explored.

The Westovers are related to Edward Winslow via his brother, Kenelm Winslow who didn’t come to Plymouth until 1632. He had been delayed in part because he was living in London learning a trade. He was a joiner, which means he could make cabinets, coffins and other furniture by cleverly joining the wood without the use of any nails. This was obviously a useful trade that could provide him an adequate living in the colony, especially as there were not many other accomplished joiners in the early years.

John Howland (11th Great Uncle) – via the Begich-Welty-Carson line

John Howland was born about 1599, probably in Fenstanton, Huntington. He came on the Mayflower in 1620 as a manservant for Governor John Carver. During the Mayflower’s voyage, Howland fell overboard during a storm, and was almost lost at sea–but luckily for his millions of descendants living today (including Presidents George Bush and George W. Bush, and Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt) he managed to grab ahold of the topsail halyards, giving the crew enough time to rescue him with a boathook.

It has been traditionally reported that John Howland was born about 1592, based on his reported age at death in the Plymouth Church Records. However, ages at death were often overstated, and that is clearly the case here. John Howland came as a servant for John Carver, which means he was under 25 years old at the time (i.e. he was born after 1595). William Bradford, in the falling-overboard incident, refers to Howland as a “lusty young man”, a term that would not likely have applied to a 28-year old given that Bradford himself was only 30–Bradford did call 21-year old John Alden a “young man” though. Howland’s wife Elizabeth was born in 1607: a 32-year old marrying a 17-year old is an unlikely circumstance. Howland’s last child was born in 1649: a 57-year old Howland would be an unlikely father. All these taken together demonstrate that Howland’s age was likely overstated by at least 5 years. Since he signed the Mayflower Compact, we can assume he was probably about 21 in 1620, so the best estimate for his birth would be about 1599.

John Howland had several brothers who also came to New England, namely Henry Howland (an ancestor to both Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford) and Arthur Howland (an ancestor to Winston Churchill).

Our connection comes from his brother, Henry Howland, my 11th great grandfather, who came to the Plymouth Colony with his brother Arthur either in the ship Fortune c.1621 or on the ship Anne with William Pierce as Master c.1623.

The earliest Massachusetts record for Henry Howland is in the allotment of cattle in Plymouth in 1624, where he appears as owner of the “black cow.” He was made a freeman in 1633. He was an early settler in Duxbury, Massachusetts, was one of the largest land holders in there, and was chosen constable in 1635.

In 1640 Henry purchased five acres of upland and an acre of marsh meadow in Duxbury, the price paid being “twelve bushells of Indian Corne.” For several years he was surveyor of highways in the town, and for nine years served on the grand jury, but in 1657 he refused to serve further on the grand inquest, apparently because he had become a Quaker and could not conscientiously perform the duties required of him.

The law against heretics in general was first enforced against the Friends, and then special laws were enacted against them. A fine of 5 pounds or a whipping was the penalty for entertaining them, and for attending their meetings one was liable to a fine of 2 pounds.

Thereafter he was persecuted by the authorities of the Colony. On the 3rd of June 1657, Ralph Allen, Sr. of Sandwich refused to serve on the grand jury, and at the next session of the court three days later he was brought before the jury for entertaining Quakers, fined and imprisoned. Within a few weeks Henry Howland, his brother Arthur, and his son Zoeth met the same fate. On 2 March 1657/58, the same day that his brother Arthur was fined £4 for permitting a Quaker meeting in his house and £5 for resisting the constable of Marshfield in the execution of his office, Henry Howland was fined ten shillings for entertaining a meeting of Quakers in his house contrary to court orders.

Henry owned land in Dartmouth in 1652. In the original purchase of Dartmouth, he is assigned one share with William Bassett. Henry was one of the original twenty-seven purchasers of what is now Freetown, Mass., and finally ended his days in Duxbury.