A Family History of Thanksgiving

A family history of Thanksgiving is bound to be a bit different than the traditional accounts of Thanksgiving we read in the media and in general history books.

These days there is an effort to “correct” the historical teachings of Thanksgiving as it was once known.

Family history has a way of re-centering it because we know what we know from our own traditions.

~ Thanksgiving is a Multi-Cultural Experience ~

The media debates whether or not turkey was part of the first Thanksgiving 400 years ago in 1621. It is a silly argument because turkey is hardly the point and the Thanksgiving of 1621 was hardly the first time Thanksgiving was celebrated.

It was not even the first Thanksgiving in North America. The settlers at Jamestown was first reported some 11 years before in 1610.

That never gets talked about, mostly because Charlie Brown wasn’t there (okay, I’m kidding).

The idea here is that Thanksgiving was actually a very British and very Christian thing to do. In fact, it was a somewhat common practice that was held at any time of the year whenever a governing authority cared to call for it.

“Thanksgiving” was a general term to denote when a community would together celebrate some sort of good news.

It might be a victory in battle, the birth of a new prince, or simply a great harvest that would ensure survival through the winter months. When things like this happened, a public call to prayer and the recognition of God was made through a declaration of Thanksgiving.

It was hardly confined to British Christians. French explorers famously celebrated Thanksgiving in 16th century Canada.

Native American cultures also celebrated a form of Thanksgiving, often recognizing Deity and nature for their survival. Thanksgiving was, for them, a way to recognize they were stewards of the Good Earth who needed to care for it.

~ Mayflower and Puritan Ancestors ~

There is an image of Mayflower passengers as being a religiously persecuted bunch who came here to worship as they wanted.

That is partly true.

But it is also true it was the riches and freedom of the New World that enticed them.

But the greater story behind that “first” Thanksgiving in 1621 was a recognition they barely survived at all. And yes, the Native Americans not only participated in that three-day feast of Thanksgiving they were likewise instrumental in survival of that colony.

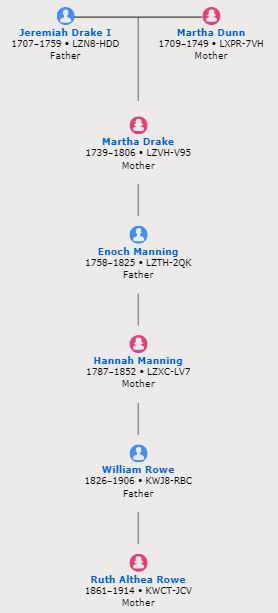

Our Westover ancestors certainly fit the mold of English Puritans. Gabriel Westover and family lived in Somerset, England, which was literally ground zero for the Puritan clashes against the Crown. Gabriel moved his family to the Netherlands, as many Puritans of that time and place did, just to protect them.

It was because of these conditions that Gabriel sent his teenage daughter, Jane, first to the New World and then a little later, he sent his son Jonah Westover, who would become the North American patriarch of the Westover family.

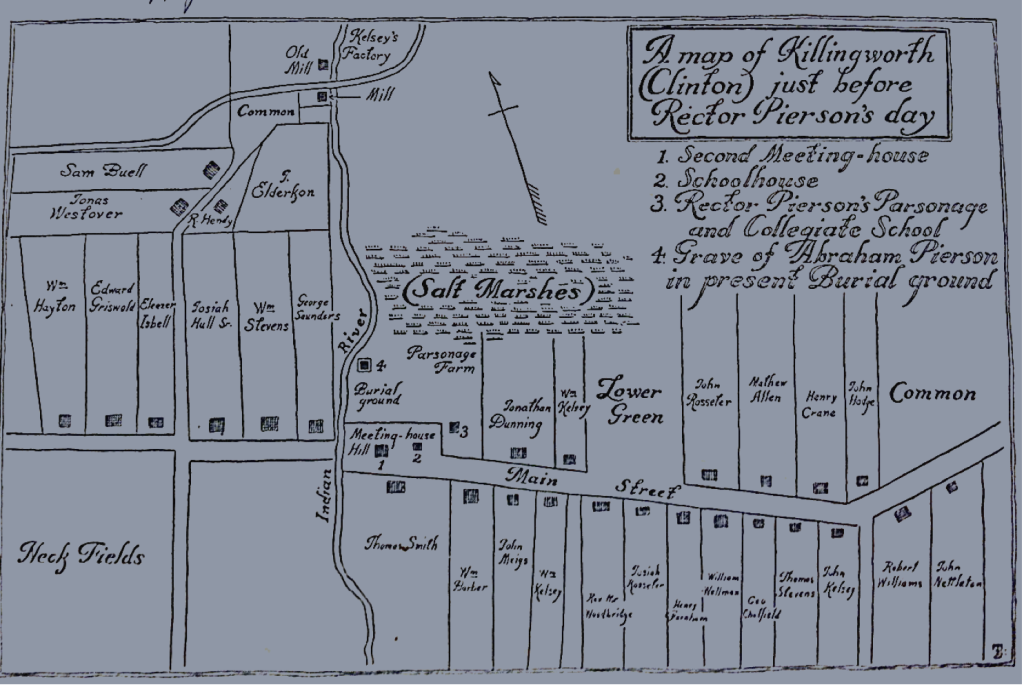

Jonah was very young when he arrived and the colony in Windsor was only a few years old. By then the traditions of Christmas and Thanksgiving were well established in Connecticut.

How do we know this?

The young media of the New World speaks of both celebrations. Much is made today of a proclamation in Boston banning Christmas but this did not actually occur until 1659. That happened nearly 40 years after the Mayflower.

So, what did they do during that time? They celebrated Christmas – albeit in a more devotional way than their English family was used to.

Christmas in England had become a raucous community event at the end of each year. It bled even into the Church of England where priests were guilty of role reversals, looking the other way at grievous sin, and participating in less-than-religious activities common to pagan celebrations of the solstice.

Christmas, in fact, was one of the reasons why the Puritans wanted out. They saw no Biblical justification for the celebration that Christmas was known as then.

But the Christmas they envisioned – one of worship, prayer and devotion – only became established due to one thing.

And that thing was Thanksgiving.

~ New England Traditions of Thanksgiving ~

Over the course of time after the “first Thanksgiving” in 1621 there are recorded many events called Thanksgiving that happened up until about 1650.

It seems that around that time the end of November – harvest season – Thanksgiving found annual declaration by colony leaders.

This well-timed tradition for Puritan settlers gave them the more festive event they longed for. It was, in their own way, more like what Christmas was viewed as in Old England.

In other words, once the church meetings were over and the prayers were said, Thanksgiving was a time to party.

Well, as much as Puritans could party.

That meant gathering as family and feasting, playing games, enjoying music and other secular pursuits not commonly associated with the Church.

Hunting games were common and, yes, since turkeys were native and abundant, that is what they hunted.

But the Thanksgiving feast was never limited to turkey alone. Venison, chicken and even pork were prepared during periods of Thanksgiving.

Food then, as now, was central to festive times together as family. From 1630 comes this neat little poem, singing the praises of pumpkin, which has been linked to the Thanksgiving celebrations of New England from the earliest time:

For pottage and puddings and custards and pies,

Our pumpkins and parsnips are common supplies:

We have pumpkins at morning and pumpkins at noon,

If it were not for pumpkins, we would be undoon.

It must be remembered that families were necessarily huge. A lot of children were born because survival was tough and required a lot of hands on the farm.

So an end-of-harvest event was a grand celebration in which family got together – perhaps for the only time during the year – and the duties of bringing and preparing food were shared.

These family gatherings were festive and could take several days.

It is important to note that Thanksgiving was considered a family event. Yes, a community might share a common date declared for Thanksgiving by a governor but rarely did one colony celebrate Thanksgiving at the same time as another.

But families got together when it best suited them – when all was safely gathered in and families were preparing for winter.

So the seasonal, end-of-harvest Thanksgiving was built on family tradition – not any kind of national calendar.

~ Thanksgiving during the 18th Century ~

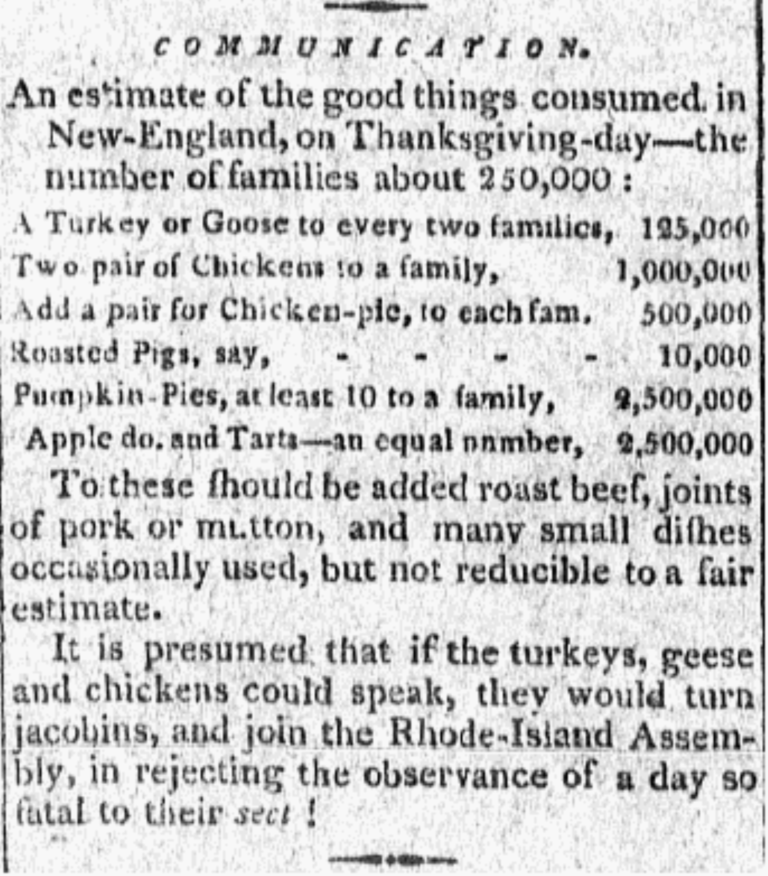

While still a British territory in the 1700s the American colonies celebrated annual Thanksgiving “seasons” that were well noted in the local media.

A newspaper report from Philadelphia in 1754 estimated that the average family prepared at ate 10 pumpkin pies at Christmas. The same article said more than 2 million turkeys were consumed in a single day on the American Continent.

Such was the popularity and commonality of Thanksgiving during the pre-revolutionary years.

Ben Franklin had a lot to say about Thanksgiving. In fact, he is famous for once trying to electrocute a turkey for Thanksgiving.

For some reason, he believed a turkey killed with electricity would be tastier than one dispatched by conventional means: decapitation. As fellow scientist William Watson wrote in 1751, Franklin claimed that “birds kill’d in this manner eat uncommonly tender.”

Franklin set out to develop a standard procedure for preparing turkeys with static electricity collected in Leyden jars. One day, while performing a demonstration of the proper way to electrocute a turkey, he mistakenly touched the electrified wire intended for the turkey while his other hand was grounded, thereby diverting the full brunt of the turkey-killing charge into his own body.

Maybe this is why we roast turkeys in Franklin’s oven, instead of by electrocution.

Thanksgiving was declared a national observance by presidential proclamation from George Washington, John Adams, and even Thomas Jefferson.

It is important to note that Jefferson was uncomfortable with the whole idea of Thanksgiving. Not that he disagreed with the virtue of gratitude. His concerns stemmed from the idea of calling citizens to prayer and recognizing God.

As governor of Virginia and later as president he proclaimed Thanksgiving anyway, saying he was merely “recommending it”, not mandating it.

By Jefferson’s time Thanksgiving was a defacto national holiday. It was so engrained as an automatic thing there was no turning back from it.

That didn’t stop several from advocating for a national holiday known as Thanksgiving.

~ Thanksgiving in the 19th Century ~

The acknowledgement of Thanksgiving which would come later on a national scale was driven by people in the mid-19th century who grew up with those gathering traditions.

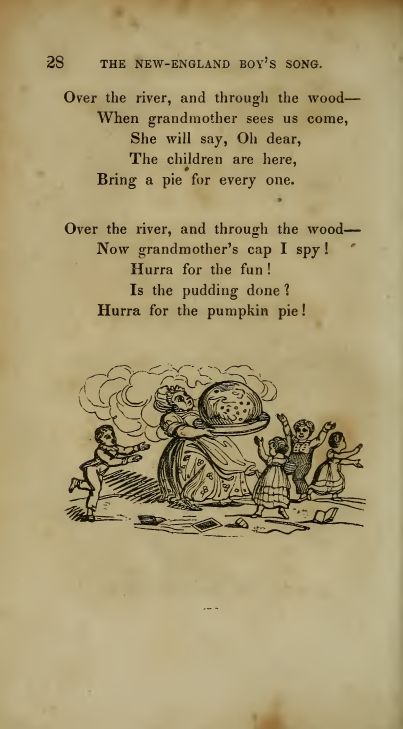

Such was the case of the creation of “Over the River and Through the Wood”, a popular Thanksgiving poem written in 1844.

It was written by an extraordinary woman named Lydia Maria Child – decades before Christmas and Thanksgiving became recognized as official holidays. It is through her efforts and others that we know that Christmas and Thanksgiving were long traditions in North America.

Lydia Maria Child was a woman ahead of her time. Born in 1802 she made her voice heard through the power of her pen. (Yes, we are related – she is a distant cousin, through the Snow line).

She was an accomplished writer, editor and civil rights activist – in the early 19th century. During her day she would be controversial and even daring in the eyes of some. In the 19th century man’s world she was a force that tackled the prickly topics of slavery, male dominance and white supremacy.

But while her individual story is fascinating, her simple poem teaches us much about what Thanksgiving was like in the early 19th century. It was, simply, the biggest family celebration of the year.

She is not the only American writer with an ancestral connection to Thanksgiving. Read this about Henry Wadsworth Longfellow – and the common Alden ancestors we share through the Snow line.

Our pioneer ancestors in Utah adopted the same Thanksgiving celebrations they brought with them from generations before. The first “Thanksgiving” was held in August of 1848, though our Westover ancestors missed it by more than a month.

But Albert Smith was there and he had great reason to observe it. Albert famously recorded his efforts to farm on the east side of the Salt Lake Valley and he recorded the miracle of the seagulls that summer. His gratitude was well noted within the pages of his journal.

Utah didn’t recognize Thanksgiving until 1851, when Brigham Young, then-governor of the Utah Territory, declared Jan. 1, 1852, a “day of praise and Thanksgiving.”

We do not have any kind of family records (that we know about) that talk of celebrating Thanksgiving in those days.

But we know from tradition that spilled forward into the 20th century that the family had a long established tradition of gathering and feasting that continues to this day.