It hasn’t even been a week since we received word that Aunt Alice passed away.

It hasn’t even been a week since we received word that Aunt Alice passed away.

Last Sunday Bunni posted on Facebook in a message broadcast to family and loved ones far and wide that at the age of 91 Alice had gone home to be with Pete.

Very quickly my Dad and my brother and I exchanged messages to each other. “We have to go,” Jay said.

We all felt that way.

Alice is the wife of my Uncle Peter Begich, my Grandpa Carl’s big brother.

You know the story of Grandpa Carl and hopefully you know the story of how Pete and his family came to know us.

Alice was such a big part of that story.

I cannot recall the year exactly, maybe 1978 or 79, but Pete and Alice and Bunni made the trip to California to be sealed together in the temple.

I cannot recall the year exactly, maybe 1978 or 79, but Pete and Alice and Bunni made the trip to California to be sealed together in the temple.

This was the first time all of us except my father had met any of my mother’s family. My Mom was understandably very nervous about the whole thing.

It was Alice who made it all so easy.

She was so sweet, so fun, so accepting – how could anyone NOT love her?

She was funny, warm, talented, and so very gracious to all of us. She had my mother silly in minutes. Alice was, in the shortest terms possible, instant family. She was simply all about love.

The news of Alice’s passing was not unexpected. When Bunni and Jim popped into Aubree’s wedding reception late last year she told me that her mother was not doing well at all.

So we were ready for that news. It was never a question whether or not we would go when the time came. We had to go. My mother would want to be represented – and we would want to remember Alice with all those who loved her as well.

On Monday, I came home from work and messaged Bunni first thing to learn the arrangements. She told me the funeral would be on Thursday.

Whew. I wasn’t sure I could make arrangements for myself that fast. But I messaged Dad and Jay again and within the hour plans were formalized. I packed a bag not knowing if when

I returned to work in the morning they would give me the time off.

We figured that if we left from my house on late Tuesday afternoon we could drive the 1500 miles there in time for the funeral and then get back later on Friday night, so I could squeeze in one more day of work into this week.

What good could come from 70 hours of driving and 3 hours of funeral?

Miracles rarely take that much time.

~ A Long Ago Trip ~

I had been to Minnesota once before in my life.

After Pete and Alice came to California Bunni and I kept up a light correspondence that lasted through my mission. I came home from the mission field on April 26th, 1984. I was home all of three months before I moved to Utah.

I think it was the following summer, in 1985, that Bunni and her parents came through Salt Lake City on a trip. I recall meeting with Bunni briefly during a stay at the KOA on North Temple in Salt Lake.

Their trip came on the heels of a visit to Salt Lake City by my Grandma. Dad called me one day and he told me she wanted to go to the recently opened Family History Library and to visit with her sister, my great aunt Elma. My job was to get Grandma around wherever she wanted to go.

So each day of that week-long visit I drove out to Ralph and Elma’s house in Kearns and drove Grandma and Elma to the library. Most days I had to work while they were at the library but on my days off I spent the day there with them.

Grandma showed me how to use a micro film reader and how to look up possible locations of family records. She very wisely encouraged me to work on my mother’s side of the family and using her direction I was soon very deeply involved in name research.

I called my mother nearly every day that week as I found more and more information that was new. I very quickly became hooked on the idea of mining my mother’s information.

So when Bunni told me she was coming through Salt Lake City and wanted to see me I was anxious to see her – so I could ask about the Begich side of my mother’s family. That side, beyond my Grandpa Carl’s parents, was unknown – and unavailable at that time through the Family History Library.

We had a delightful visit and after a long conversation she thought it was best for me to come visit. I told her of my desire to see Grandma Begich. She told me she would discuss it with her father and that if anyone could make such a visit possible it would be her father – or herself if necessary.

Some months later — I don’t recall the date – I set out on my own from Salt Lake for northern Minnesota. My mother was well aware of the trip. We discussed it. She doubted Grandma Begich would see me but she encouraged me to get as much information as I could, especially pictures.

I look back on it now and it was a little crazy. A 22 year old kid driving by himself across the plains to somewhere he had never been. But it was an adventure to me. I drove 24 hours straight and stopped only for gas, my curiosity growing it seemed by the mile. Wyoming and Nebraska were kind of boring but as I made my way through Iowa and the landscape began to change I started to wonder what was ahead.

By the time I had arrived in Minnesota and specifically in Gilbert I was clearly in a different place – something entirely new and old all at the same time.

But I was welcomed with opened arms, good food and lots of love. That would be my enduring memory of this entire trip – it was filled with love.

Looking back on it now and the record I made at the time of what I learned there are so many things I would do different. Not that I did anything wrong. But age and perspective have a way of making you see things you didn’t see at the time.

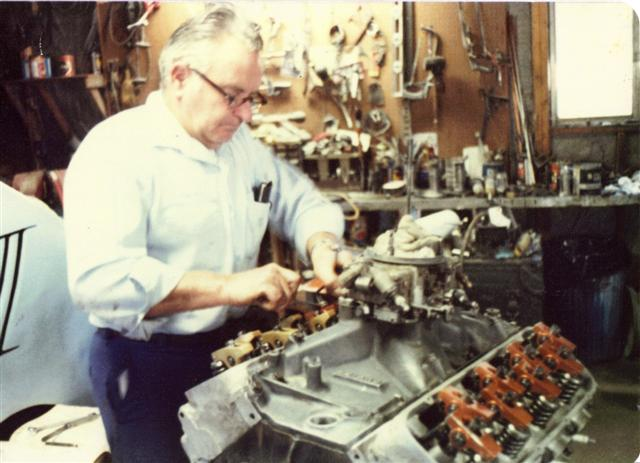

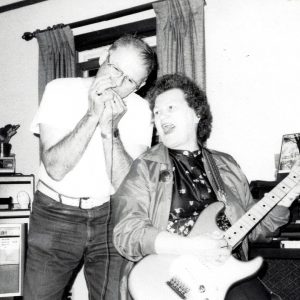

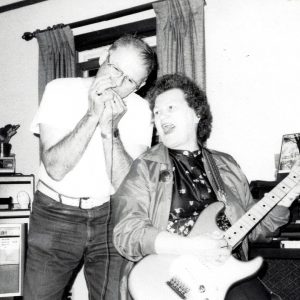

The focus really was on getting a chance to visit Grandma Begich. Each day I was there Pete would disappear for a while to discuss it with his mother. And each day he would come home with hopeful words that by the end of the week it could possibly happen. As the days passed I was given the grand tour of the area and I heard many stories of family. Pete and Alice completely immersed me in their world, sharing their music and their love of simple things. I did copy a lot of photos that Pete had and I called my Mom a time or two to share things with her.

As my time there wound down I could see Pete’s anxiety growing over the visit with Grandma. I can recall a conversation around the dinner table where he expressed his frustration and said, “I think you should just show up.” Bunni then said that she wanted a crack a Grandma, that she could convince her to see me.

I was very torn over the whole thing. My mother had long before expressed to me that she felt growing up that she wasn’t wanted, that the family in Minnesota didn’t want to know her. How mother came to feel that way she never explained. But she felt that way and that fueled her doubts about me being able to visit Grandma. I wanted badly to prove mother wrong about all that.

But at the same time, as Pete would explain how Grandma would put her hands up around her ears and start to cry, I couldn’t just not acknowledge her feelings. The thought occurred to me that I was about the age Carl was when he died. What if I never came home to my mother from this trip? Would Mother then understand?

It occurred to me that I was putting the emphasis on the wrong thing. Yes, if I could see Grandma that would be a great thing. If I could hear her story from her own lips that would be even better. If I could get to know her that would be the best.

But if that would put her in the pit of grief for the rest of her days what good would we be accomplishing?

My Begich experience up to that point had been about love – love extended to me. How could I love Grandma enough to honor her request to avoid that pain?

So I told Pete and Bunni it was okay. It was enough for me to be there, to see them, to learn what I could.

Love had brought us together. And love would solve this in time.

~ 33 Years Later ~

We stayed in Bozeman last Tuesday night. We got up early on Wednesday and left at 5:30 am – and drove all day, getting to Duluth, Minnesota before 9pm. We were going to make it for the funeral just fine.

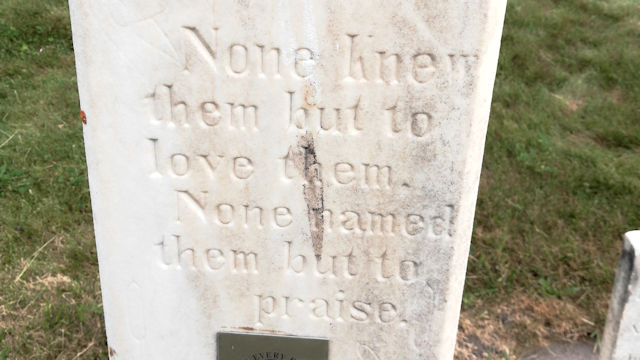

We got to Gilbert the next morning a little early and decided to see what we could of the cemetery. We very quickly saw where Pete was buried and where Alice would be. Then we started to look for others.

Why hadn’t I gone to the cemetery when I was there 3 decades before? It never dawned on me then to do so – plus all the people I wanted to see then were still living.

Why hadn’t I gone to the cemetery when I was there 3 decades before? It never dawned on me then to do so – plus all the people I wanted to see then were still living.

A quick search revealed that Grandpa and Grandma Begich were not in the same cemetery with Pete – they were over in Eveleth. So we jumped in the car and drove a few miles to Eveleth – the boyhood home of my Grandfather.

Again, why hadn’t I visited Eveleth thirty years ago?

We poked around a bit trying to find the cemetery. We found the Catholic church and stopped to get a picture of it. While there a man was kind enough to give us directions to the cemetery.

We drove there, saw the thousands of headstones and did the best we could in the very few minutes we had. But it wasn’t meant to be – we did not find Grandma and Grandpa.

But it was time to go. Time to head back to Gilbert and pay our respects to Alice – and anyone who might be there from the family. We didn’t know what to expect. I knew some of them were getting along in years and I was worried that they, like Alice, were maybe feeling the effects of age and maybe could not attend.

We walked into the tiny funeral home and saw the many people gathering. After a few quick hellos with Jim and Bunni we were at last introduced to Aunt Tillie and Aunt Belle – my grandpa Carl’s sisters. They welcomed us with wide smiles and warm hearts. We dove into conversation so very quickly that it seemed a shame we had to end it for the start of the funeral service.

We walked into the tiny funeral home and saw the many people gathering. After a few quick hellos with Jim and Bunni we were at last introduced to Aunt Tillie and Aunt Belle – my grandpa Carl’s sisters. They welcomed us with wide smiles and warm hearts. We dove into conversation so very quickly that it seemed a shame we had to end it for the start of the funeral service.

The tributes to Alice were nice. I so wanted to stand up and shout, “We love her too!”. But at the same time it was nice to enter into her world as kind of a fly on the wall and to hear others say the things about her we already knew.

As things concluded, and Alice’s casket was wheeled out of the room, I heard Aunt Belle – age 94 and strong in every way – say very softly, and respectfully, in a voice full of love – “Bye, Alice”. It broke my heart a little bit because of the sadness in her tone. But I quickly understood it wasn’t because of loss – it was because of love. And I wondered as I thought about these two great ladies – Alice and Belle – and what they must have shared over the years.

Events at the cemetery were very brief, and we returned for a long as we could stay to the VFW hall next door to the funeral home, where a luncheon had been prepared for the family.

Events at the cemetery were very brief, and we returned for a long as we could stay to the VFW hall next door to the funeral home, where a luncheon had been prepared for the family.

In the conversations that ensued and the great things that were expressed we learned some things that we had not known before. These are small things, but they are great things, at least to me. Here are some things we didn’t know:

1. Grandpa Carl was an artist. Aunt Belle told me he could draw anything. She said that if she had to do a homework assignment for school that he could help her. When she needed Sir Francis Drake, Carl drew him. This small detail, of course, is really reminiscent of my mother, who had the same great ability.

2. Aunt Tillie doesn’t believe for a second the story behind Carl’s death. She too recounted his lack of love for the water, something we had heard before. But she also noted with great suspicion that he died days after the war was declared over and that his drowning was a very unlikely scenario – that he would never go near the water.

3. Aunt Tillie said she was in possession of the letters Carl wrote home to their parents. We want to get copies of those letters so we can add them to the collection we already have.

4. Bunni told the story of a memorial service held for Carl after the war. Grandma Begich was presented with a flag from that traditional ceremony. She told them they could keep the flag, that she wanted her son back.

5. Aunt Tillie indicated that she had been in contact with Sandy Minot, Pete’s daughter from his first marriage. Sandy has been pushing her to write Grandma Begich’s story and Tillie said she was deeply involved in that effort. This is perhaps the most exciting news of all.

6. Belle told me her mother came over from Yugoslavia at the age of 17 and that she left because the future she saw for herself there was only as a housekeeper for the Catholic Church. She said that she had to have the sponsorship of a cousin who lived in Oregon to make the trip.

7. It was in Oregon that she met Grandpa Begich, who had gone there for a job in logging. They moved to Minnesota because a cousin had told him about the mining jobs.

By far the most rewarding part of these precious few hours of Alice’s funeral was just being in the presence of these family members, all of whom expressed love and a few who shed a few tears.

In the end, it was again all about love. We felt it in abundance.

~ A Happy Coincidence ~

Aunt Belle is 94 and Aunt Tillie is just five years behind her. Both use walkers and have a little difficulty with their mobility but at the same time I found them both to be remarkably conversant and so very sharp. They both had a lot to say.

Belle told me that she was recently in the paper and I made a point to snag it to see what it said. I’m thrilled to share it here, because I think it showcases so nicely her demeanor and personality.

Like all of our family of this generation she had quite an experience during the war and I’m grateful for this record and the pictures that went along with it:

Rosie the Riveter was the star of a campaign aimed at recruiting female workers for defense industries during World War II — and Katherine “Belle” Begich, now Vukelich, was an enthusiastic participant.

The Eveleth native, now going on 94, became a Rosie the Riveter, joining the thousands of American women who entered the workforce during the war. This was because male enlistment left holes in the industrial labor force. Between 1940 and 1945, the female percentage of the U.S. workforce increased from 27 percent to nearly 37 percent, and by 1945 nearly one out of every four married women worked outside the home.

While women during World War II worked in a variety of positions previously closed to them, the aviation industry saw the greatest increase in female workers — including Vukelich. More than 310,000 women worked in the U.S. aircraft industry in 1943, making up 65 percent of the industry’s total workforce (compared to just 1 percent in the pre-war years). The munitions industry also heavily recruited women workers — including Vukelich.

Based in small part on a real-life munitions worker, but primarily a fictitious character, the strong, bandanna-clad Rosie became one of the most successful recruitment tools in American history, and the most iconic image of working women in the World War II era. Though women who entered the workforce during World War II were crucial to the war effort, their pay continued to lag far behind their male counterparts: Female workers rarely earned more than 50 percent of male wages. The Saturday Evening Post in 1943 published a cover image by the artist Norman Rockwell, portraying Rosie with a flag in the background and a copy of Adolf Hitler’s racist tract “Mein Kampf” under her feet.

From the Mesabi Daily News:

VIRGINIA — It was the 1940s and her three brothers were serving in World War II — Carl Begich in Germany, Mike Begich in Africa, Pete Begich in the Philippines. So Katherine “Belle” Begich, now Vukelich, wanted to do her patriotic part.

Vukelich, soon to be 94, described it this way in an interview at her home in Virginia’s Washington Manor. “I graduated in 1942 from Eveleth High School. There were no jobs to be had and I wanted a job. I said, ‘I’ve got to do something for the war effort and that’s what I did.'” Women found employment as electricians, welders and riveters in defense plants.

Vukelich, soon to be 94, described it this way in an interview at her home in Virginia’s Washington Manor. “I graduated in 1942 from Eveleth High School. There were no jobs to be had and I wanted a job. I said, ‘I’ve got to do something for the war effort and that’s what I did.'” Women found employment as electricians, welders and riveters in defense plants.

Vukelich grew up in the Eveleth mining location, populated mostly by Slovenians and Croatians, known as Kurjavas, or Chickentown, near the Spruce Mine. “I had a friend from Milwaukee, Tillie Tonko,” she said. “She invited me to come to Milwaukee. She said I could do defense work. There were are a lot of girls down there from the Range. So I took a train to Milwaukee. Tillie said, ‘You can live in my mother’s house. Her name is Mrs. Snidarsich.’ Other girls from the Range were Marion Krall, Josephine Trost, Ann and Rose Lopac. For $7 a week I got a breakfast and a bag lunch and supper, had a little apartment by myself in her huge house. We lived on East Knapp Street. Mrs. Snidarsich took me by street car here and there to apply for a job.”

Vukelich was hired by Nesco, a company that made pots and pans which had been converted to a munitions plant, she said. “I ran a machine called an indenter. We were on an assembly line. I made the firing pin hole in the shell. We made 20-mm anti aircraft shells. First I would make a cup of a little sheet of brass. If I put a shell in the wrong way, the mechanic would have to fix it.” She is proud to say that she was able to hold five long shells at once. She remembers when a woman got her long red hair hair stuck in a drill press — she had forgotten to put on the protector over her hair.

Vukelich, then 19, came down with infected tonsils that had to be removed, and she went home to Eveleth to recuperate. But it didn’t keep her down for long. She had a sister who worked with the Northwest Glider Company in St. Paul. “I got itchy feet and had to get another job,” Vukelich said. “I was hired at Northwest Airlines at Holman Field (Twin Cities) where they had B-24 Liberator bombers.

Vukelich, then 19, came down with infected tonsils that had to be removed, and she went home to Eveleth to recuperate. But it didn’t keep her down for long. She had a sister who worked with the Northwest Glider Company in St. Paul. “I got itchy feet and had to get another job,” Vukelich said. “I was hired at Northwest Airlines at Holman Field (Twin Cities) where they had B-24 Liberator bombers.

“First I had to go to school to learn all parts of the plane and the lingo. I was drilling and buffing rivets. I liked being in the bomb bay where bombs were stored when the plane was in flight for war. I became a parts runner, had a moped and went from hangar to hangar. These airplanes came from Texas with just the bare necessities to fly. We had to install plumbing, electric and hydraulic lines before we could let the planes go back to Texas. I was there a couple years. And in 1945 President Franklin Delano Roosevelt announced that the war was over. We all got laid off except a skeleton crew that was left to clean up.”

After the war she came home to the Iron Range and found employment at Reed’s and Sears department stores. Her fiance, Paul Vukelich of Virginia, came home from the service and the two were married in 1948. They had three children, Steven, Nicholas and Donna. Belle Vukelich later attended the Eveleth Area Vocational-Technical School and became an LPN. She was employed by the East Range Clinic and worked for the late Dr. George Ewens, dermatologist, and also at the ERC pharmacy with pharmacist Dennis Greben and others. She retired in 1981 and “became a homemaker again,” she said with a smile. “And that’s the end of my story.”

Asked about her feelings on helping with the war effort, she said, “I got thanks from people. I’m glad I did it. The girls — that’s what we did during the war. The girls left home and put on these ‘toilet seat’ covers (head coverings) and coveralls. We didn’t make much money. My mother cut up all my uniforms for making rag rugs.”

She said, “I feel proud that I did it. I have no regrets.” Then she added with a chuckle, “I left a couple nice boyfriends down there.” And sometimes married men would try to make advances — to whom she’d say, “Leave me alone. I’m a single woman, you’re a married man with lovely children and a beautiful wife. Oh, was I mad. They didn’t bother me again.”

She said, “I feel proud that I did it. I have no regrets.” Then she added with a chuckle, “I left a couple nice boyfriends down there.” And sometimes married men would try to make advances — to whom she’d say, “Leave me alone. I’m a single woman, you’re a married man with lovely children and a beautiful wife. Oh, was I mad. They didn’t bother me again.”

She and her husband Paul Vukelich — who died in 2017 one month shy of 96 — were married 69 years. “It would have been 70 in June,” she said. He had played in a tamburitza band, she said.

Vukelich has one surviving sister, Tillie Gulan, who also resides at Washington Manor. Her other sisters were Mary Yurkovich and Rose Biondich.

~ What Happens Now ~

I’ve taken the time to write this because this is family history in the making. It is, in reality, a story that dates back 100 years to a time when our Begich great-grandparents came to the USA.

And we are continuing to write it.

We must build on these tender relationships. We need to remain in contact with Belle and Tillie and to come to know them better. We must learn about their lives and families. They must learn about ours.

We’re part of each other.

Perhaps we can make up with them some of the time we never had with Grandma Begich and Grandpa Carl. We can most certainly share with them the love we have for our collective families.

I see great love there. I see great pride there in heritage. It is exciting to get to know them. I pray what we have started here continues for generations to come.