Somewhere Daddy is Sleeping

/

1 Comment

While researching for another project I found myself on the Library…

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/westovers49sm.jpg

647

1150

Jeff Westover

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/logo22.png

Jeff Westover2020-02-16 21:42:582024-03-03 16:03:50Finding Family in the News

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/westovers49sm.jpg

647

1150

Jeff Westover

https://westoverfamilyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/logo22.png

Jeff Westover2020-02-16 21:42:582024-03-03 16:03:50Finding Family in the News

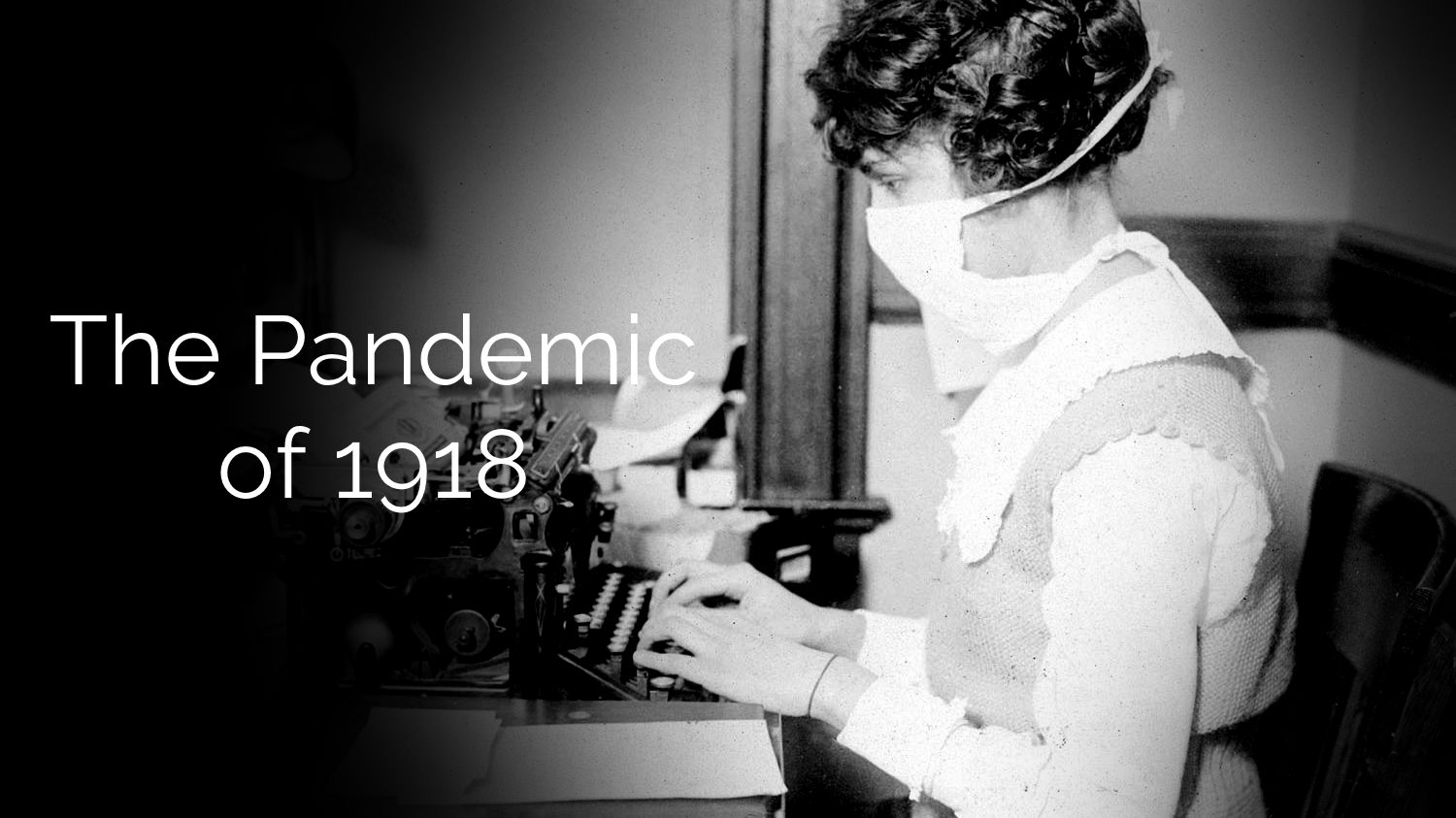

Pandemics in Our Family History

January of 2020 will go down in history for the outbreak of what…

The War Experience of Grandpa Carl

I always try to spend a little time with my grandfather, Carl…

Yes, Del Shannon is a Westover

If you are of a certain age or just a fan of popular American…